Displaced Communities

![]() BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

displaced by Hitler & Stalin; 95%+)

![]() GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

(over 200,000 expelled, imprisoned, displaced, emigrated; 98.5% total)

![]() VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

![]() DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

15% of German population)

![]() GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

(100-200,000 expelled after WWI)

![]() GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

(over 3,000,000 expelled

and displaced; 95% total)

![]() GERMANS OF HUNGARY

GERMANS OF HUNGARY

(over 100,000 expelled, over

300,000 displaced; 88% of total)

![]() GERMANS OF ROMANIA

GERMANS OF ROMANIA

(over 700,000 or 91.5% displaced by Hitler, USSR, & emigration)

![]() US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

(10,906+ interned & blacklisted) NEW!

![]() GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

(over 5,000,000 expelled and displaced, nearly 100%) COMING SOON

![]() GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

(nearly 1,000,000 to Germany and Kazakhstan) COMING SOON

Other Information

![]() OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

(documentaries, interviews, speeches)

![]() Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

(for updates, events, announcements)

![]() "Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

"Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

![]() "British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

"British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

![]() "British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

"British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

![]() From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

(memoir about wartime flight & Jewish, Polish, & German daily life near Auschwitz) NEW!

![]() Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

![]() The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

![]() Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

![]() Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

![]() Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

![]() Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

![]() Suggested Resources & Organisations

Suggested Resources & Organisations

![]() In Memoriam: Your Expellee

In Memoriam: Your Expellee

Relatives & Survivors

![]() Submit content and information

Submit content and information

![]() How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

the vanQUished volga german community

![]() Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

![]() Send

this Article to a Friend

Send

this Article to a Friend

HOW

TO CITE THIS SCHOLARLY ESSAY: Institute

for Research of Expelled Germans. "The vanquished Volga

German community." http://expelledgermans.org/volgagermans.htm

(accessed Day-Month-Year).

The unofficial

flag of the Volga Germans, with grain symbolizing the agrarian

heritage of German settlers in Russia

Total population change resulting from expulsion: all ~379,630 Volga Germans removed to Kazakhstan (nearly 100%) along with the near remainder of USSR's at least 1,084,828 ethnic Germans (see Germans of Russia). As many as 300,000 may have died during the expulsion of all Germans in the Soviet Union (or 30% total).

For an analysis of the history and fate of the other ethnic German minourity communities of Russia and the Soviet Union, see Germans of Russia/USSR/Ukraine.

_______________________________________

![]() History of Settlement, Culture, Autonomy, and

Religion

History of Settlement, Culture, Autonomy, and

Religion

![]() History of Expulsion

History of Expulsion

![]() Sources/Bibliography

Sources/Bibliography

![]() Population

Statistics

Population

Statistics

![]() Famous Persons

Famous Persons

![]() Suggested

Websites and Organisations

Suggested

Websites and Organisations

_________________________________

History of Volga German Settlement, Culture, Autonomy, and Religion

In order to interpret the process of subsidised ethnic German frontier settlement in Russia, it is necessary to frame it under the context of the historical trends of Russian imperial expansion, modernisation, and so-called 'Westernisation.' By the 18th century, the Russian Empire had grown into one of the most expansive sovereign dominions the world had yet encountered. The consolidating conquests of Ivan the Great, Ivan the Terrible, and Peter the Great from the 16th century until the 18th rapidly forged the truncated regional East Slavic principalities into a militarised and politically united realm expanding from the Baltic to Alaska. The empire's administration consisted of an ethnic Slavic Orthodox hegemon stratified over regional Tatar, Turkic, Mongol, and Siberian vassals and tributaries stretching across the Eurasian plateau. Peter the Great's portentous and obstinent policies of modernisation and 'Europeanisation' initiated an increasingly auspicious commercial and technical relationship between the growing Russian Empire and the Western European domains. Previously under the rule of the Turkic Golden Horde and the Tatars, and culturally dismissed as 'Oriental' and 'barbarian' by Western bourgeois intellectuals, Russia sought to place itself on the world stage as a culturally and politically advanced national space. It was out of this new internationalist cultural connection that Russia's empress Catherine the Great (an ethnic German herself) published several manifestos calling for extensive and partially subsidised immigration from Western European states to the largely uncultivated and unoccupied fertile Russian frontier lands:

'We shall allow all foreigners to come into our empire, in order to take up residence in all provinces wherever it is agreeable to each of them...[those struggling with persecution or starvation] may report for help to the ministers and residents at our embassies. These [manifestos] shall not only send them to Russia at our expense without objection, but shall also provide them with money for the journey...'

Although a plethora of ethnic groups hastily exploited Catherine's

request, a significant constituent of settlers were Protestants

of ethnic German origin from the German states of Hessen,

Pfalz (the Rheinland Palatinate), and Bavaria after 1770.

The departure of German farmers and frontiersmen from Germany

and to the very distant Russian Empire was stimulated by a

variety of factors: including regional internecine famine,

political turmoil, and occasional or feared persecution of

Protestants by Catholic sovereigns and princes. The overwhelming

majority of these Germans settled along the Volga river basin

in central Russia, where they would remain for nearly 200

years until their expulsion. Here, they became known as Volga

Germans (Wolgadeutsche), and gradually developed

a distinct traditional farming culture with their own liturgical

maxims and German dialect. Hundreds of small villages appeared

rapidly on both banks of the central Volga, especially the

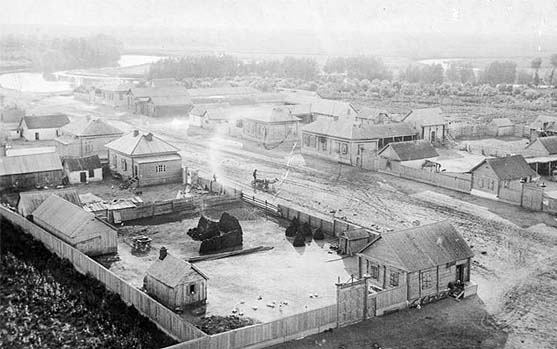

center of Kosakenstadt (literally 'Cossack

City' in German) outside of the majour Russian city of Saratov.

The pronounced geographic, cultural, and political isolation

of the Volga Germans, combined with the Russian government's

promise of autonomy and fiscal protection, meant that this

distinct foreign community was able to retain its independent

German genetics, identity, language, and Protestant religion

despite being constituents of the Russian Empire and being

separated from Germany for centuries. In general, this divorced

the Volga Germans from experiencing the rampant political

and class turmoil that swept Russia throughout the 19th and

early 20th centuries. It was during this time that many of

the Volga Germans further departed from Russia for Canada

and the northern United States, stimulated by entrepreneurial

opportunity, poor harvests along the Volga, political instability

in Russia, and greater religious freedom during a time of

increasing Russian religious and ethnic integral conservatism.

Through trade and financial opportunity, small Volga German

populations traded with and settled in nearby urban and commercial

centres, although most remained confined primarily to isolated

German-speaking villages.

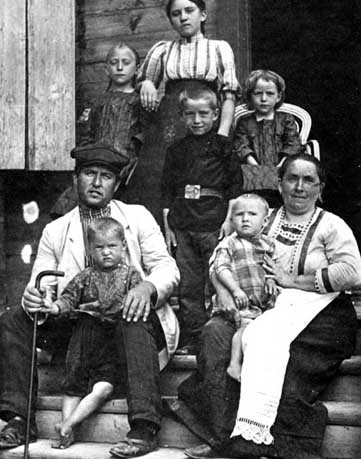

The Volga Germans were an extremely agriculture-oriented community that heavily revolved around physical labour, farming, the harvest, the community, and the church. The early Volga German villages operated similarly to those of the German Mennonites and Anabaptists, another important minourity that settled at the same time under Catherine's adjuration. Volga German societies were highly stratified: elders and church leaders were greatly venerated as wise village advisors and community leaders. Salient Germanic rituals, such as those surrounding the Jul (Yule), Christmas, weddings, and harvest and drinking festivals like the 'Kerbfest' flourished and further maintained the cultural independence of the Volga Germans from mainstream Russian society and that of the Germany their ancestors left behind . Lutheranism and the Reformed Church were revered with high esteem without persecution from the official Orthodox establishment. Foreign visitors from Germany and Western Europe were surprised to see that Volga German villages were very Germanic in character and appearance, illustrating the marked political and cultural autonomy guaranteed by their isolation and the passivity of the Russian state (Long 1988, 61).

The intensely agricultural drive of Volga German culture, as well as the auspicious environmental fertility of the Volga basin caused the settled Volga German population to grow rapidly more quickly than native Russian and East Slavic populations. From 1834 to 1850, for example, the standard replenishment rate per 1,000 Russians was 50-70 lives, whilst it was over 500 for the Volga Germans (Norka). This includes further immigration from Germany. Although emigration onto the Volga continued in decreasing quantities, bountiful agricultural output allowed Volga Germans to escape the rampant starvation and crisis that was increasingly befalling Russian and Ukrainian serfs in times of tremendous political uncertainty prior to the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917.

Volga Germans worship at a Lutheran church on the Volga river

(from lhm.org)

from volgagermans.net

from volgagermans.net

An early photo of a Volga German village that soon became

part of Soviet 'Engels' in the Volga German autonomous republic

The autonomy of the Volga Germans reversed in an increasingly nationalistic Russia

Despite this relatively independent political and cultural existence, the Volga Germans came under internecine assaults from the Russian military when they occupied the region in order to combat revolts among the adjacent Kuban Cossacks, other Cossack polities and chiefdoms, and Qara-Kyrgyz (Kazakh) nomad bands, then living under Kokkandi Muslim rule, occasionally raided Russia and the Volga area and captured slaves for the slave trade networks in South Asia and the Muslim world (Volga Germans). Retaliating Russian soldiers occasionally burnt and raided German villages along the way. In general, the Russian government followed with propitiatory indemnity and new land grants to displaced German families. So too, the status of the Volga German ethnic communities gradually came under threat from the changing political behaviour of the increasingly despotic Russian government throughout the late 19th century. As occurred in hitherto-autonomous Russian Poland, the Russian monarchy effectively dissolved the near-total political, religious, and legal autonomy bestowed on the Volga Germans by Catherine the Great a century prior. New compulsory military forms were extended for the first time to apply to the German minourities, including conscription, quartering regulations, and new taxation. The provincial autonomy around Kosakenstadt was subsumed under direct Russian hegemony. After the Franco-Prussian War, in which the now-reunified Germany forced the Second French Empire in 1871 into total collapse, the Russian government dissolved the autonomy of the Volga Germans, fearing a pan-Germanic irredentist expansion of Germany to the East under the context of Drang nach Osten ('Urge to the East') (Volga Germans). The Russian state responded to political fragmentation by self-strengthening that symied the regional independence that non-Russian minourities had enjoyed for centuries.

The disasters of World War I exacerbated inter-ethnic conflict within the broken Russian Empire and greatly reduced the political and social status of the Volga Germans, as an increasingly-nationalistic Russian society engaged in brutal war against an equally-nationalistic Germany. In 1915, 'liquidation laws' excoriated the German minourity as inherently perfidious to the Russian war effort, depicting them as a suspicious and subversive minourity with irredentist and pan-Germanist designs. German populations were targeted with involuntary confiscations, arrests, and relocations (Germans from Russia Heritage Collection). In few cases, pogroms targeted ethnic German civilians in Russia with violent assaults and displacement, unable to discern Germans invading from the west from ethnic Germans who had lived in Russia for centuries and had been completely separated from the predatory political aims of the distant German state. It has been estimated that World War I, the Russian Civil War between Bolsheviks and monarchists (1917-1923), famine, and inter-ethnic contumacy reduced the Volga German population from ~500,000 in 1914 to 330,000 by 1920 (Koch 1974, 284).

The Volga German experience and significant autonomy under the Soviet Union

After the triumph of the Red Army in the Russian Civil War after 1920, Vladimir Lenin forever changed the political and social experience of the Volga Germans in Russia, and with simultaneously both very negative and highly positive results. Like the rest of the Soviet Union, the Volga Germans were forced away from any independent, private, and non-agricultural traditional artisanry and onto massive collective farms. The centuries of local isolation from general Russian society was dismantled in the interests of socialist liberation and collectivisation. The intention of the Bolshevik administration was to create a well-fed and self-sufficient union that was uniformly exposed to the Marxist-Leninist worldview. Volga German society was disrupted and reformed, and community farmers were forced from their homes (like most Soviet citizens) to work on distant collectives. During this time, Volga German populations increasingly moved from their disparate and isolated farming villages and into majour adjacent commercial and urban centres. Under Joseph Stalin's intensive industrialisation programme (ruled 1924-1953), this collectivisation campaign was also intended to fuel the militarisation and advancement of the Soviet Union via income from grain exports in order to build self-sufficient 'socialism in one country'. However, although this collectivisation campaign undeniably transformed a broken peasant land into an industrialised superpower in under a decade that soon destroyed even the Third Reich, it also created some of the worst famines and mass deaths in history. The Ukrainians, Ingush, Tatars (see article), Chechens (see article), and Volga Germans lost millions through rampant starvation after 1921. Volga Germans lost as much as 10-20% of their population through starvation, according to several sometimes disputed sources. Over 48,000 may have died, and 70,000 fled (Long 1992, 523). From 1926 until 1939, the population of the Volga German community centred around the main settlements at Kossakenstadt (later 'Engels') declined from 379,630 (66.4% of the region) to 366,685 (60.5%), primarily due to forced recirculation throughout the Soviet Union and death from the traumas of collectivisation (Concordia University).

Volga Germans, forced off of their successful outputs from their own German farms, were required to labour under improvident Soviet collectivisation directives that failed to deliver tools, equipment, and labour animals. They even confiscated as much as 42% of the already-deficient collective crop yields when the Volga German labourers were starving to death, forcing many Volga Germans to eat rats, dogs, and insects (Long 1992, 513). Any wealthy, outwardly religious, or contumacious Volga Germans were either expelled or shot, including 300 men and priests in one moment without trials (Long 1992, 518). It must be acknowledged that these famines caused by collectivisation were not intentional, although they were exacerbated greatly by Soviet improvidence and the Stalinist mentality to achieve self-sufficiency at any cost.

After the disastrous artificial famine, the situation among the Volga Germans gradually normalised. Vladimir Lenin's interpretation of Marxism promoted the establishment of superficial ethnic political franchise and autonomy to each of the Soviet Union's recognized ethnic groups, allowing the creation of a universal proletarian Comintern that encompassed all ethnic groups behind the banner of revolution. The Volga German minourity was given the newly-established Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) shortly before Lenin's death in 1924. This ethnic republic lived under strict Marxist political, social, and ideological administration and regulation. Religion -- central to the independent Volga German identity -- was abolished entirely, and the traditions of the Volga German minourity were effectively demolished. The Russian language was instated as compulsory in instruction, trade, and work, and the use of German was greatly discouraged, although it retained a superficial co-equal official status with Russian in the republic. Non-German minourities were brought into the region heavily, including Jews, Russians, Koreans, Finns, Chuvash, Turks, Caucasus peoples, and Circassians. The region was markedly 'Sovietified' and 'Russified'. The previous Volga German centre of Kosakenstadt was renamed Engels, after the second ideological founder of Communism. The Volga German ASSR had a population of roughly 600,000 by the time of its dissolution in 1942, although this included non-German people (Flags of the World). Due to the very ephemeral existence of the Volga German ASSR, very few Germans made any sincere ideological committment to the proletarian revolution. Many joined the White Army against Lenin's forces in the Russian Civil War, likely perceiving the Red Army as an atheist scourge that sought to trample on their 200-year independence after they overthrew the Imperial regime. There was very little interracial marriage despite the Soviets' demands for the destruction of racism and integral nationalism (Pohl 1999, 35). This perceived lack of participation and assimilation by the Germans must have inspired Stalin's future suspicions of the Volga Germans as being collabourative, subversive, and of dubious loyalty to the Soviet state that required unquestioning obeisance. The head of the government of the Volga German ASSR was Gustav Klinger, a Volga German Communist. Despite this somewhat tumultuous process of nationalisation, collectivisation, acculturation, and autonomy, the Volga Germans increasingly remained relatively isolated and stable until the German invasion in 1941 and their universal expulsion because of their ethnicity by the Soviet authorities.

from the European

Heritage Library

The flag of the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

(from flagspot.net)

The official seal of the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist

Republic. The Communist rhetoric and imagery was promulgated

by the Soviets instead of the Volga Germans themselves (from

the European Heritage Library)

History of Expulsion, and the Situation of the Volga Germans in Diaspora in Kazakhstan

The Volga German ASSR enjoyed relative economic and political stability until Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. However, the Volga Germans (like most other ethnic minourities) suffered under Stalin's so-called 'Great Terror', the rampant execution and imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of those deemed to be political opponents, Trotskyites or left-wing Communists, reactionaries, and independence-seeking nationalists. 38,000 Volga Germans were arrested under Order 00439, and those not executed immediately were shipped to Siberia for compulsory labour and internment. Over 72,000 Germans in the Soviet Union altogether were targeted as perfidious and antisocial elements during the 'Great Terror', especially because of their perceived unverified or insufficiently enthusiastic embrace of the new Marxist-Leninist order (Gellately 2000, 237). Nonetheless, it is an exaggeration and inaccurate to describe the initial experience of Volga Germans under Soviet rule after the famine as one of intensive oppression, murder, and purging. Other ethnic groups (especially the Russians, Ukrainians, Caucasians, Circassians, and Kazakhs) suffered far more than the the Volga German minourity, which consistently maintained a degree of geographic and political autonomy. Arguably, it was Germany's invasion that started the Volga Germans' calamities and expulsions, but it was the Soviet government that issued the order to universally remove all traces of the German ethnicity from their homeland after centuries of peaceful and productive settlement.

The pervasive ideology that dominated German society was the integral nationalist worldview of Volk und Rasse (People/nation and race) and Volksdeutsche, whereby Germany was defined by its racial and genetic qualities rather than a recognised political space. As a result, Germany (and Austria) were viewed as the home for all Germans in diaspora. Ethnic Germans outside of the Reich were depicted as being oppressed and subjugated, yearning for liberation by the German military. Deputy Rudolf Hess in his speech at the Nuremberg Parteitag of 1933 described Germany as a ' Heimat...für alle Deutschen der Welt' (Homeland for all Germans in the world). A political campaign appealing to Germans in the Baltic, Poland, and ostensibly Russia encouraged a programme called 'Heim ins Reich' ([come] home to the Reich). Although no documents or references to the Volga Germans are found in Mein Kampf or any other majour political manifesto of National Socialism, Hitler's ideological plans for an ethnic German expansion eastward into Soviet Russia inevitably sought to 'liberate' the German minourity from the calumny and perversions of so-called 'Jewish Bolshevism'. Although the Volga Germans inevitably felt a cultural connection with the invading Germans and many openly joined them against the Soviets and the Jews, it must be remembered that the Volga Germans had been separated from Germany proper for nearly 200 years and did not even experience Germany's reunification in 1871. So too, Soviet censorship completely shielded the Volga German ASSR from any racialist or pan-Germanist polemics. It is possible that many Volga Germans had never heard of Adolf Hitler or National Socialism except through the admonitions and derisions of Soviet propaganda, and therefore had no ideological or epistemological understanding and adherence to racialism or Nazism. Even the pan-German nationalist Otto von Bismarck overtly showed no interest in the Volga Germans, considering them to be too politically adulterated after centuries of Russian rule and having abandoned Germany (Long 1988, 61). These factors greatly contrasted from Stalin's suspicious perceptions of the Volga Germans as an inherently subversive and potentially pan-Germanic aggitator that had to be removed. The Volga Germans were to be universally proscribed as an irredentist and perfidious 'Fifth Column' simply because of their ethnicity and language.

In 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression, a treaty that determined the ephemeral sovereignty of the two superpowers over Eastern Europe. Interestingly, Stalin distributed German flags with the Swastika symbol to the Volga German ASSR in celebration (Pohl 1999, 32). This auspicious peace was short-lived. On 22 June, 1941, the Third Reich broke the pact and invaded under Operation Barbarossa. Realizing that a sizable ethnic German minourity resided within the USSR's own borders with a pan-Germanic nationalist behemoth rapidly approaching the Volga and claiming to 'liberate' its racial kin, the infamously brutal purges of Joseph Stalin turned from potential party traitors and reactionaries to the Volga Germans as a whole. True to Stalinist administrative policy (as enacted against the expelled Crimean Tatars, Ingush, and Chechens as well), it was more efficient to be safe than sorry in a time of total war against a ruthless Nazi invader.

Although it is common in historiography to assert that Stalin began persecuting the Volga Germans upon Hitler's invasion in 1941, Stalin seems to have planned to expel the entire population even during the non-aggression peacetime with Germany. Stalin began to gradually remove Volga Germans as early as 1940 and diminish their political autonomy, less than a year after the celebrated pact. Infuriated by the persecution of ethnic Germans under Soviet auspices, Hitler responded by intensifying the expulsion and murder of Jews and Slavs to be dumped off at the Soviet border in retaliation (Kershaw 2008, 683). The supposed 'persecution of Germans' was cited as one of the reasons for the Nazi invasion. This was, of course, politically convenient and exaggerated for to justify Nazi military decisions. Propaganda films released by the German government and illegally smuggled into the Soviet Union depicted the supposed agony of German life under the jackboots of communism and Russian, "Jewish-influenced" dictatorship. The 1935 film "Friesennot" (click here to see our vide0) tells the story of a life of socialist stagnation, heavy overtaxation (even though there were usually no taxes in the Soviet Union), and no religious freedom for highly religious Volga Germans. The protagonist in the film is half-Russian, half-Frisian (from the Germanic minourity of the Netherlands). In response to the misery suffered by Soviet minorities, the peasants rise up and murder their commisars. Comments are made in the film that cast out the characters in the film who were supposedly immoral and treacherous enough to mix their German genes with those of Slavs, implying that as long as Germans live "unliberated" in the Soviet Union, their racial purity will be in jeopardy. Interesting, the film was banned by Germany after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and then legalised as soon as the war began and the Soviets again became the enemy!

In 1941 following the Nazi invasion, Stalin formally abolished the Volga German ASSR (although the term officially remained until 1942) and initiated the removal of the entire German race from the Soviet Union. Simply because of their ethnicity and language, all Germans were either to be immediately executed or sent to forced labour camps and gulags in Siberia and Kazakhstan (the Kazakh SSR). The divers lifestyles and ideological convictions of these expellees were ignored in order to ensure the removal of a perceived threat from Soviet society during the total war. The expelled Baltic Germans, Crimean Black Sea Germans, Caucasus Germans, Bessarabian Germans (see article), and Volga Germans had not been anywhere near Germany for 200 years nor had they had any direct exposure to Adolf Hitler's racialist policies or ideology, yet they were identified as inherently hostile due to cultural stereotypes, Germanophobia, and hysteria.

Nonetheless, to understand the ethnic policies of the Soviet Union, one must view the period from the perspective of the Soviet government: many among German minorities had indeed cooperated with the invading Nazi armies in conquered nations like Poland, Yugoslavia (Danube Swabians), France, and Czechoslovakia (Sudeten Germans). It went to follow that the large German minority in the Soviet Union of over a million may welcome the German military, sabotage railway access to undermine the Soviet war effort, or offer intelligence on Soviet strategies or military locations. This is why the German minority was only one persecuted among many others after the German invasion. As early as the 1930s and the Ukrainian famine (Holodomor), Stalin had already developed a minority policy that made entire ethnic groups considered to be suspicious and politically unreliable.

The Soviet government issued a reflection on the 'hostile' status of the German ethnicity with the following report:

'According

to reliable reports by military authorities, there are in

the Volga province among its German population thousands and

ten-thousands of diversionists and spies...None of the Germans

living in the Volga district has informed the Soviet authorities

of the presence of such a large number of diversionists and

spies among the Volga Germans...In order to forestall undesirable

consequences of this nature and to avoid bloodshed, the Presidium

of the Supreme Soviet has found it necessary to resettle the

entire German population...' (Koch 1974, 284).

Tatar, Ingush, & Chechen sources are from

(Naimark 2001, 13). Map is

copyrighted. CLICK MAP TO

ENLARGE

The Soviets did not expel their German minourity after they had been verified to collabourate with invading Nazi soldiers or SS death squads; most were not given the chance to collabourate. The expulsion of nearly all Germans was pre-emptive, and planned ideally to remove the Germans before the Third Reich could invade their regions and gain new collabourating allies among the Volga Germans. As a result, persons were forced from their homes before they even had a chance to betray the Soviet Union or support Hitler, or exemplify their guilt or betrayal of Marxism-Leninism or the Soviet state. However, the Soviets were unable to fully complete the removal of more than a million Germans of the Soviet Union and nearly 500,000 Volga Germans by the time the Blitzkrieg arrived. The invading German army claimed to incoporate over 300,000 Germans of the USSR (Volga Germans and other Soviet Germans) under their control who fled with the retreating Nazis back to Germany during the gradual Soviet triumph. The majourity of these ethnic Germans conscripted into the Nazi military were not from the Volga German community, since the Soviet expulsions had preceded the invasion by the Third Reich. Supposedly, 200,000 Volga- and non-Volga Germans under Nazi control were repatriated by the Soviets by 1945 for execution or expulsion after the Soviets captured them from occupied Germany or the Wartheland in Poland (Giesinger 1981). In total, all of the more than 400,000 Volga Germans and the near entirety of the remaining 700,000 ethnic Germans from throughout the Soviet Union were shipped out by 1945, excluded from society and imprisoned. One source estimates as many that as 1.2 million ethnic German civilians were forced out of their homes (IRIN). Almost all of the at least 366,000 Volga Germans from the former Volga German autonomous republic went with them (Szovjet Gulag).

It must be acknowledged that the German civilians were far from the most victimised ethnic group. The Tatars (see article), Ingush, and Chechen Muslims (see article), the Koreans, Tibetan Buddhist Kalmyks, Meskhetians, and Galician Poles were massively expelled and arguably suffered far more than the Volga Germans. The near entirety of these ethnic groups (except the Koreans and Poles) were expelled completely to Kazakhstan along with the Volga Germans. Every single Ingush was thrown out of his home because of few internecine instances of war-time collabouration (Naimark 2002, 13). All were deemed guilty of collabourating with the invading Germans or espousing pan-Turkic or Islamist tendencies that threatened the Soviet Union in a time of horrific war with an invading Nazi horde. So too, as many as 20,000 Polish officers were executed by the Soviet army in the forests of Katyn, and over 2,000,000 Poles were expelled from eastern Poland to the newly-annexed regions of Eastern Pomerania, Prussia, and Posen (Posznania) that was now depopulated of Germans by force.

The ancient

communities of the Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, and Volga Germans

that preceded any Nazi crimes almost completely disappeared.

Deportees were given notice cards to inform them of their

coming removal and the seizure of their property, and often

were given less than fifteen minutes to gather what possessions

they could into one bag before leaving their homes behind

(Concordia University 2). These whole communities

were deported to Siberia, the Uzbek SSR, and the Kazakh SSR

on train rides that often took weeks or even months with almost

no food, no heating, and no sanitation for the freezing nights

or cooling for the scorching days of the Central Asian steppe

climate, leading to the death of thousands on the way out

of starvation, heatstroke, and hypothermia. 400 Volga German

children and infants were reported to be found dead on one

train convoy alone (Burleigh 2001, 496). Near-starving

prisoners were effectively dumped into the wasteland, with

children forced to remain in camps until they reach adulthood

after an ideological re-education. The German language was

banned, and manifestations of German culture were considered

reactionary and officially deprecated or outlawed altogether.

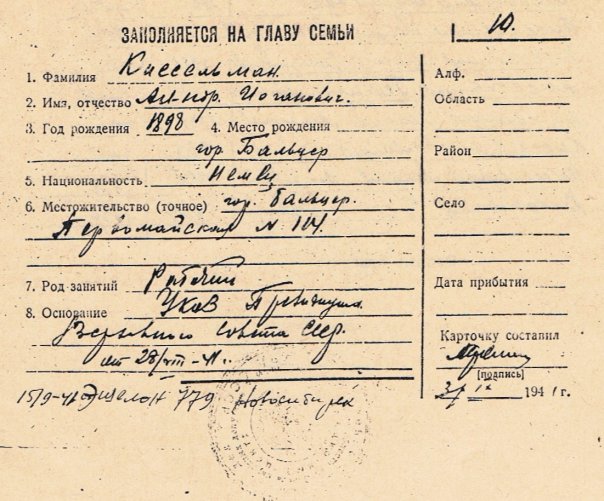

An

eviction notice given by the Soviet authorities to a German

family warning them of their immediate expulsion and the seizure

of their property (Image: Concordia

University 2). CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Upon arrival in the gulags and work camps, Tatars, Ingush, Chechens, Koreans, and Volga Germans were subject to imprisonment and forced labour in delinquent work units called the 'Trut Army' (meaning 'labour army'), housed in makeshift shacks in the wastelands of Central Asia and Siberia under the thorough observation of Soviet officials (the Spezkomendatura). With the great majourity not even given a chance to become guilty of treason prior to their removal, the Volga German ethnicity was now proscribed altogether as a criminal and treacherous population. Some worked as far away as Kolyma in the far east of Siberia towards Alaska in some of the most remote and freezing gulags. The prisoner labour effort was fed by as many as 151 train convoys departing from 19 train stations prior to Khrushchev's liberalisation of Soviet ethnic policy. The deported 'hostile peoples' were regulated by as many as 20,000 NKVD officers and guards diverted from the war effort to keep men, women, and children working or to prevent their revolt (Concordia University 2).

Soviet troops even parachuted into the former Volga German SSR dressed as German soldiers in order to ascertain how many of the few Germans who remained after or during the expulsions would give them safe housing. The many found guilty of this sedition were executed outright. Anyone holding a German or Swastika flag – and many did in order to express the same independent ethnic identity that Lenin espoused – was either shot or deported. Ironically, many of these available flags were sent there by Stalin in celebration of the non-aggression pact of 1939 (Pohl 1999, 32).

Calculating the total number dead and displaced is historiographically complicated due to a variety of factors, including nebulous or partial statistics published by the Soviet government, the near-closure of the Soviet archives to NGOs and independent researchers, and the proneness to bias of a number of authors and motives. Many sources estimate that as many as 52% of all Volga Germans may have died en route to Kazakhstan and, upon arrival, 40% of those survivors subsequently died under forced labour exersion (IRIN). According to another source, at least 300,000 total German civilians died from starvation during the expulsions, or 30% total (Germans from Russia Heritage Collection). According to the lowest estimates, at least 17.7% of all expelled Tatars who were resettled in Uzbekistan (often together with Volga Germans) died en route, and 23.7% of all Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, and Barachais by 1948 (Weitz 2003, 81). Other sources calculate that only 82% of all ethnic Germans in the Soviet orbit were expelled (Weitz 2003, 79). This reduced statistic only considers the initial assault and deportation programme of the Soviet authorities, and does not reflect the complete impact of Soviet policy on the German, Tatar, or Caucasian minourities. The planned total removal of the German identity from the Soviet Union was only obstructed because of its interruption by the German invasion, the subsequent shortage of manpower, the loss of control over the Volga region where most Germans were settled, and the liberalisation of Soviet ethnic policy under the regime of Nikita Khrushchev. Other Soviet documents originating with the Soviet NKVD record the forced removal of 1,084,828 ethnic Germans from the USSR, nearly the entirety of all German-speaking citizens within the Union (Weitz 2003, 80).

Post-war emigration of Volga Germans, and the status of

Volga Germans in Muslim Kazakhstan today:

The Volga German community, which had flourished in Russia for nearly 200 years, had been vanquished. The hundreds of settler villages were demolished or repopulated by good Soviets. The polar arguments that their destruction was the fault of Adolf Hitler's invasion or Stalin's brutality are both equally valid. Nonetheless, Russians today insist (with a great deal of truth) that it was Stalin's hard-handed policies that were necessary to allow the Soviet Union to defeat the Third Reich when the rest of the world could not. Many insist that if Stalin had not removed the significant Muslim and ethnic German populations from the front, Russian nationalists argue, the Soviets may not have been able to subdue the Nazi scourge. Russians also understandably respond to the ethnicity-profiled expulsion and starvation of nearly 1,084,828 German Soviet civilians (and 400,000 Volga Germans) by citing that more than 20,600,000 Soviets died during the war timeframe (The History Place). Nonetheless, an unfortunate cost of World War II was that the largely innocent Volga German cvilians were forcibly relocated to the rural wastelands of distant Kazakhstan and assimilated either into the culture of the general Soviet identity or of other Germans from the rest of the Soviet Union who were expelled with them from 1940-45 as well. As a result of this displacement, the Volga German cultural heritage itself was almost completely lost, and is largely reconstructed today by descendents of 19th-century Volga German immigrant families in Canada, Brazil, Argentina, and Germany.

Stalin's death in 1953 changed the demographic and political doctrine of the USSR. Nikita Khrushchev (ruled 1953-64) pursued a policy of 'de-Stalinization' that eschewed the 'excesses' of his predecessor. After his so-called 'Secret Speech', Khrushchev lifted the exclusionary ethnicity-specific injunctions against the Tatars and Germans, considering them to be outmoded legacies of Stalin's erratic 'paranoia'. The criminal Volga Germans were now de jure rehabilitated. Khrushchev allowed the Volga Germans to leave the prisons and camps in the Kazakh SSR to any territory within the Communist orbit, including East Germany, Russia, or their Volga homeland itself. Many Germans entered Kazakh society as labourers in Kazakh cities like Alma Ata and especially Karaganda, where the majourity of the population consisted of German expatriats prior to their mass emigration and replacement by ethnic Kazakhs.

The West

German government actively encouraged immigration of ethnic

Germans under the Law of Return, which offered citizenship

to all expelled persons of German blood (read our article

on this historical sponsourship). As many as a million persons

of German blood were given refugee status in Germany -- and

a portion thereof citizenship -- since 1991, and even those

unable to speak German until 1998 (Brown 2003, 233).

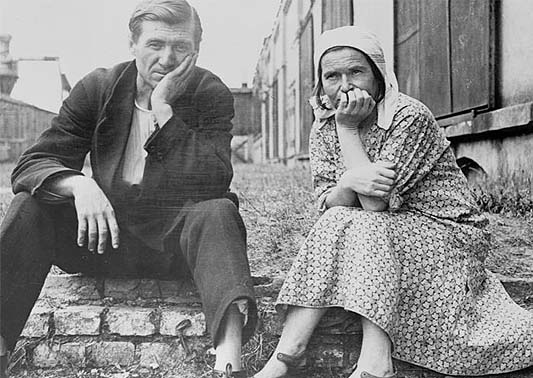

Volga Germans languishing in refugee camps in Germany after

Khruschev released them from Stalin's gulags of Central Asian

SSRs

Although this political liberalisation within the Soviet authority seemed auspicious for the expatriated Volga Germans still languishing in the desolate steppe of Kazakhstan, a concomitant phenomenon of partial Russification pervaded throughout the rest of Soviet history until its collapse. The Germans, now no longer an officially-sponsored independent ethnic group and with their autonomous republic dismantled, were required to learn Russian and Kazakh. Marked discrimination occurred against the Germans, Kalmyks, Karelijan Finns, Ingush, Bashkirs, and Tatars for their associations with the hated Nazi enemy and antisocial perfidy against the Soviet state. Ethnic Germans were not even allowed to study at the University of Moscow, the focal point of a decent Soviet education and intellectual liberation, until 1970 (IRIN). Few Volga Germans spoke the language of their heritage fluently after only a few generations. Germans were forced to assimilate into the new Russo-Soviet culture in the opulent Russified Kazakh capital of Alma Ata/Almaty. Few Volga Germans returned to the Volga river of their ancestors, as the journey was far too difficult and expensive, not to mention the fact that the Kazakh SSR was becoming a rapidly-industrialised republic compared with the poor rural countryside of the Volga and Engels. The vast majourity of expelled Germans fled to Germany as part of one of the largest refugee communities of the 20th century. The German 'Law of Return' (Rückkehrgesetz) allows those of displaced German blood to return to Germany to attain full citizenship and subsidy for their journey, although this policy has diminished due to wide-scale non-German immigration to Germany (Ahonen 2004, 109). Some 2.3 million persons left Russia and Kazakhstan for Germany and other countries alongside the millions of expelled Germans from Eastern Europe (Phalnikar 2007). Most today live in Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Kazakhstan. By the time of the USSR's collapse, there were 946,855 Germans in Kazakhstan, at 5.8% of the population (IRIN). By 1999, there were only 353,441 due to mass expatriation, assimilation, and emigration to Germany (Brown 2005, 626). Over 600,000 Germans left Kazakhstan for Germany in the 1990's alone (Minourities at Risk). By 1999, there were only 353,441 left in post-Soviet Kazakhstan (IRIN). Many formerly German towns in Kazakhstan have been seemingly abandoned, with empty homes adorned with rows of "for sale" signs and new ethnic Kazakh inhabitants (Brown 2003, 233). During this timeframe, so many expelled Germans were departing Russia and Kazakhstan that the German government even criticised Russia for not establishing an autonomous province for the Germans to assuage Germany's swamped immigration problem of German expellees (Tagliabue). Today, officially 2% of Kazakhstan (~300,000) is ethnic German (CIA World Factbook). There are roughly 597,212 Germans living in Russia today, mostly along the Volga and in the majour cities like Saratov and Moscow (perepis2002.ru). Small displaced German communities have also settled in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan along with Russian labourers and entrepreneurs.

Despite these privations, many Volga Germans have proudly retained their Germanic culture, language, ethnic identity, and the tale of their plight and forced labour in the wastelands of Central Asia. Many Germans in Kazakhstan today strive to return to what they call the Fatherland, with 33,000 petitioning for emigration in 2002 alone (IRIN). Kazakhstan's Germans are experiencing a nationalistic resurgence of ethnic, cultural, and linguistic consciousness. Today, the most salient civil rights group representing ethnic German interests is the German-Kazakhstani Association for Entrepreneurs (deutsch-kasachstanische Assoziation der Unternehmer) led by Alexander Dederer, also called 'Wiedergeburt' ('rebirth'). Their official website is available here. It is an organisation primarily geared towards commercial affairs and development, rather than historiographic, academic, or civil rights commemoration.

Some 'returning' Germans have experienced great difficulty emigrating because of the new preference by the German government for Turkish, Romanian, Polish, and Bulgarian immigration. So too, many Volga Germans in Kazakhstan have little or no fluency in German anymore. Until 1998, the German government awarded citizenship to persons of German blood even if they did not speak German, their language forcibly replaced by Russian and Kazakh through Soviet assimilation and proscription policies (Brown 2003, 233). Thereafter, German expatriats in Kazakhstan have been required to fervently study German through domestic and foreign-trained language teachers in order to successfully qualify for German citizenship. This further imposes economic difficulties and disillusionment of identity among the German minourity. Further, the regime of President for Life Nursultan Nazarbayev, who is typically derided in liberal democratic countries as a dictator, has created an uncertain climate of political and cultural opportunities for minourity groups critical of government policy or the behaviour of the Kazakh SSR. As a result of this pensive uncertainty among Kazakhstani Germans, over 2,000 have actually returned from Germany to Kazakhstan in only the last few years (Phalnikar 2007).

Interestingly, at the same time, Putin's Russia is responding to an abysmally low birthrate among Slavic women in Russia by spending up to €80,000,000 by 2012 to subsidise the return of the descendents of expelled Volga Germans for labour and job creation. The Russian government has invested in German-language education centres in Siberia and the Volga as well.

Alexander Dederer, the leader of the German-Kazakhstani Association

for Entrepreneurs (image: IRIN)

There are a number of international and local expellee interest groups emanating from Danube Swabian diaspora communities, particularly in Germany, Canada, and the United States. The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, the Center for Volga German Studies at Concordia University, and many other groups actively emphasize the history of expulsions in their frequent assemblies and cultural gatherings at universities, college campuses, local clubs, and in newspapers. In February of 2010, hundreds of scholars, survivors, researchers, donators, human rights representatives, and even diplomats and figures from the United Nations gathered for the first international assembly commemorating the expulsion of Germans at the Community College of Meramec in St. Louis, Missouri. Called "The Forgotten Genocide," the two-day conference included a large art gallery, press interviews, roundtable academic discussions, survivors' recollections, and dozens of speakers from diverse fields and motivations. Director James Mayfield of the Institute for Research of Expelled Germans represented the destroyed Volga German community by giving a detailed 25-minute speech and answering a number of stimulated commentaries (see speech videos below). The unique event even caught the attention of newspapers and forums in Poland and Germany, with both critical and positive commentary.

(article continues below past photos)

James Mayfield, Director of the Institute for Research of

Expelled Germans, speaks on the Volga Germans at an academic

conference in St. Louis, Missouri (Click HERE

to see the rest of the speech segments and more)

The art gallery of "The Forgotten Genocide" conference

in St. Louis, Missouri, February 2010 (CLICK

TO ENLARGE)

Another wall of "The Forgotten Genocide" conference (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

The story of the Volga German experience is a tumutulous one. These farming settlers were vastly distanced from Germany, its racialist ideological maxims, and its calls for expansion to the east by almost a thousand miles. They did not even see the reunification of Germany in 1871, nor did most even have a chance to betray the Soviet Union and support the Nazi armies prior to their expulsion. Despite this, they were considered universally 'dangerous' by the Stalin regime due to ethnic generalisation and entirely removed before most even had the chance to collabourate with the Nazis. An entire history disappeared, leaving as many as 300,000 civilians dead (according to the highest estimates) in the process on top of at least 400,000 other German civilians who died in the other expulsions carried out by the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Poland after World War II.

Ahonen, Pertti. After the Expulsion: West Germany and Eastern Europe 1945-1990. New York, NY: Oxford Press, 2004.

Brown, Andrew J. " The Germans of Germany and the Germans of Kazakhstan: A Eurasian Volk in the Twilight of Diaspora." Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 57, No. 4 (Jun., 2005): 625-634.

Brown,

Kate. A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland

to Soviet Heartland. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 2003.

Burleigh, Michael. The Third Reich: A New History. Hill and Wang, 2001.

CIA World Factbook

Concordia

University. "The Center for Volga German Studies."

http://cvgs.cu-portland.edu/history/AutonomousRepublic.cfm.

Concordia University 2. "Deportation (1941)." http://cvgs.cu-portland.edu/history/Deportation.cfm

Flags of the World. "Volga German ASSR (Soviet Union, 1918-1942)." http://flagspot.net/flags/su-wd.html.

Gellately, Robert and Kiernan, Ben. The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Germans from Russia Heritage Collection. "A People on the Move: Germans in Russia and in the Former Soviet Union: 1763 - 1997." North Dakota State University. http://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/history_culture/history/people.html.

Giesinger, A. From Catherine to Khruschev: The Story of Russia's Germans. Lincoln, NE: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1981.

Investigation Discovery (I.D.) Channel's "Gang Nation," Episode "Russia"

IRIN. "Kazakhstan: A Special Report on ethnic Germans." http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=28051.

Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.

Koch, Fred C. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763 to the Present. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1974.

Long, James. From Priviledged to Dispossessed. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

Long, James. "The Volga Germans and the Famine of 1921." Russian Review, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Oct., 1992): 510-525.

Minourities at Risk. "Assessment for Germans in Kazakhstan." Center for International Development and Conflict Management. http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/mar/assessment.asp?groupId=70502.

Naimark, Norman. Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard U Press, 2002.

Norka: A German Colony in Russia. "Agriculture." http://www.volgagermans.net/norka/agriculture.html.

Phalnikar, Sonia. "Russia hopes to lure back ethnic Germans." http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,2772792,00.html.

Pohl, Otto. Ethnic cleansing in the USSR, 1937-1949. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999.

Tagliabue, John. "Bonn Urges Russia to Restore Land for its Ethnic Germans." New York Times, 11 January, 1992.

The History Place. "Statistics of World War II." http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/timeline/statistics.htm.

Russian Census: "National composition of population" (perepis2002.ru)

Szovjet Gulag. "The Eight Deported Nations." http://www.gulag.hu/mass_deport_1940.htm.

Volga Germans. "A Brief History of the Volga Germans." http://www.webbitt.com/volga/history.html.

Weitz, Eric D. A Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Suggested reference:

Brown, Andrew J. " The Germans of Germany and the Germans of Kazakhstan: A Eurasian Volk in the Twilight of Diaspora." Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 57, No. 4 (Jun., 2005): 625-634.

1834- approximately 108,000 Germans along the Volga

1860's- 216,000

1897- 345,000

1914- 500,000 around Saratov, ~650,000 in Volga basin region total

1918-20- famine, war, mass expulsions, and pogroms during war with Germany drops Volga population to 330,000

1926- 379,630 (approximately 66.4% of Volga German autonomous republic)

1939- 366,685 (approx. 60.5% of Volga German ASSR, decline due to migration within USSR, and collectivisation)

1939-45- entire population expelled to Kazakh SSR and Siberia, plus nearly all Germans in USSR (1,084,828). As many as 300,000 of Russia's more than 1 million ethnic Germans may have died as a result of the expulsions (or 30% total).

1970s- mass emigration to West and East Germany out of Kazakh SSR. Assimilation into Germany.

1989- 957,518 Germans in Kazakh SSR (5.8%). Continued emigration to West Germany.

1990s- increased mass emigration to Germany after fall of USSR. ~600,000 leave Kazakhstan.

1999- at least 353,441 Germans (including Volga Germans and other Russia Germans) still in Kazakhstan (2.4%).

2009- some 597,212 ethnic Germans in Russia today (Volga Germans and other Germans). Russia is subsidising Germans to return from Germany to the land from which they were originally expelled (see article).

Sources-

[1],

[2], [3],

[4],

[5],

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9], Weitz 2003, 80; and

Koch 1974, 284.

Joseph Kessler- the 5th bishop of Tiraspol in 1904.

Alfred Koch- born in Kazakhstan 1962, head of Russia's privatization agency. Significant economist working under Anatoly Chubais, the chief doctor of Russia's move towards capitalism.

Gustav Klinger (1867-1937)- head of the Volga German ASSR throughout its duration

Harold Bauer (1908-42)- winner of the United States Medal of Honor

Suggested Websites and Organisations

The Center for Volga German Studies at Concordia University - click here.

Volga Germans at webbitt.com - click here.

Germans from Russia Heritage Collection - click here.

Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (for Germans in Kazakhstan) - click here.

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia - click here.

Russian Germans International - a Facebook group based in Kansas representing Volga Germans altogether

Deutsch-Kasachstanische Assoziation der Unternehmer, the leading representative of Germans expelled to Kazakhstan.

Volgaland, Country of the Volga Germans - an organisation promoting political autonomy or greater cultural rights for the Volga German minority in Russia and Kazakhstan