Displaced Communities

![]() BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

displaced by Hitler & Stalin; 95%+)

![]() GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

(over 200,000 expelled, imprisoned, displaced, emigrated; 98.5% total)

![]() VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

![]() DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

15% of German population)

![]() GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

(100-200,000 expelled after WWI)

![]() GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

(over 3,000,000 expelled

and displaced; 95% total)

![]() GERMANS OF HUNGARY

GERMANS OF HUNGARY

(over 100,000 expelled, over

300,000 displaced; 88% of total)

![]() GERMANS OF ROMANIA

GERMANS OF ROMANIA

(over 700,000 or 91.5% displaced by Hitler, USSR, & emigration)

![]() US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

(10,906+ interned & blacklisted) NEW!

![]() GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

(over 5,000,000 expelled and displaced, nearly 100%) COMING SOON

![]() GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

(nearly 1,000,000 to Germany and Kazakhstan) COMING SOON

Other Information

![]() OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

(documentaries, interviews, speeches)

![]() Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

(for updates, events, announcements)

![]() "Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

"Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

![]() "British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

"British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

![]() "British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

"British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

![]() From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

(memoir about wartime flight & Jewish, Polish, & German daily life near Auschwitz) NEW!

![]() Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

![]() The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

![]() Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

![]() Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

![]() Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

![]() Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

![]() Suggested Resources & Organisations

Suggested Resources & Organisations

![]() In Memoriam: Your Expellee

In Memoriam: Your Expellee

Relatives & Survivors

![]() Submit content and information

Submit content and information

![]() How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

the expelled & displaced german Community of hungary

![]() Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

![]() Send

this Article to a Friend

Send

this Article to a Friend

HOW TO CITE THIS SCHOLARLY ESSAY: Institute for Research of Expelled Germans. "The expelled German community of Hungary." http://expelledgermans.org/hungarygermans.htm (accessed Day-Month-Year).

The unofficial shield of the Germans of Hungary, representing

Buda Castle, the Christian cross, the agriculture cart of

the German settlers, and the river separating Buda and Pest

(designed by Josef de Ponte for the Association of Germans

from Hungary)

Included German minourity groups in this region: Danube Swabians, Transylvania Saxons

Total population change resulting from expulsion and displacement: from ~477,000 to only 56,918 ~88% loss

_______________________________________

![]() History of Settlement and Culture

History of Settlement and Culture

![]() History of Expulsion

History of Expulsion

![]() Sources/Bibliography

Sources/Bibliography

![]() Population

Statistics

Population

Statistics

![]() Famous Persons

Famous Persons

![]() Suggested

Websites and Organisations

Suggested

Websites and Organisations

_______________________________________

History of Settlement, Culture, and Adaptation to Hungarian Nationality

Ethnic German communities settled in the lands of the Hungarian Crown in several phases as part of the longstanding political, commercial, and religious affiliation between the German Empire, Habsburg Austria, and the Kingdom of Hungary. Although small villages of German farmers appeared on the Hungarian-German borders since the Christianisation of Hungary in 1000, the first wave of marked German settlement in Hungarian lands occurred in the 13th century, when the sovereigns of Hungary invited farmers from Germany to settle on the fertile steppes. These settlers were granted significant cultural and social autonomy. Subsequently, the main bulk of settlement and cultural exchange between the Germanic world and the Hungarians occurred during the rule of the German Habsburg Empire over the Kingdom of Hungary from 1526-1918. German-speaking people became the disproportionately dominant ethnic caste throughout the imperial realm. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Habsburg emperors subsidised the immigration of peasants and entrepreneurs from the Catholic regions of southern Germany into Croatia, Hungary, the Banat and Vojvodina (today straddling Romania, Hungary, and Serbia), and Transylvania. The ample ethnic rights of the Germans in Austria were extetended to these German colonists in Hungary as well (Kann 1979, 460). This large-scale ethnic German immigration was in part intended to resettle the Hungarian cities of Buda and Pest that had been almost completely depopulated by the pillaging and displacement wrought by the Muslim janissaries of the Ottoman Empire. Most settled along the Danube river, coming primarily from Baden, Württemburg, Bavaria, and Hessen. As most spoke the Swabian vernaculars of German and came from the southwestern region of Swabia, the German settlers in Hungary became generally known as Danube Swabians (Donauschwaben), although their rural villages spoke a number of dialects and retained various regional traditions (Molnar 2001, 181). The prevalent majority of Danube Swabians were Catholic due to the compulsion of the Habsburg state and the religious culture of southern Germany. Additionally, small populations of Danube Swabians gradually adopted the Lutheran, Uniate, and Calvinist faiths that proliferated throughout Hungary after the 16th century as a counterbalance to Austrian Catholic primacy. As the Hungarian Crown ruled over modern Croatia and Slovakia, large Danube Swabian communities appeared in both countries, including nearly 160,000 in Croatia alone (Lumans 1993, 117).

The ethnic

German settlers in Hungary enjoyed significant autonomy and

franchise rights that exacerbated the Hungarians' irritation

at their inferiour ethno-political status within the Habsburg

Empire. Although there are many cases of Hungarian and German

rural farmers actively cooperating, there are also numerous

reports of inter-ethnic pogrom violence caused by this franchise

struggle, including mutually against the Jews (Lendvai

2004, 43). Although most Danube Swabians were agricultural

farmers, the German entrepreneurs in urban centres quickly

became even wealthier than the Hungarians, controlling larger

estates and landholdings due to cultural and economic support

by the German-speaking Austrian sovereigns (Gal 1993,

340). The repopulation of Buda and Pest by these Swabian

immigrants gave Germans great control over a significant economic

centre. Buda was 54% Danube Swabian even as late as 1869 (Heiszler

2002, 48). Preßburg (today Bratislava, Slovakia) as one

of the significant cultural and political hubs of Central

Europe was also majority German. Even rural German communities

were given limited self-government and voivodships that gradually

subsumed the influence of Hungarian farmers in their own homeland

(Encyclopædia Britannica). In Transylvania, the Transylvania

Saxons (as well as Hungarians) had rights that greatly

diminished those of the native Romanians (Kann 1979, 287).

The presence and rights of the Danube Swabians throughout

the Habsburg Empire was sustained by direct subsidy (including

free livestock, land, and tax exemptions) from the Colonial

Commission after 1766, especially under Maria Theresa and

Leopold II (Kann 1979, 200). In all of the lands

of the Hungarian Crown (Hungary, modern Slovakia and Croatia),

the total population of Danube Swabians was about 1,200,000

in 1843, 1,955,250 in 1880 (12.5% of the total population

of the Hungarian kingdom lands), 2,116,578 by 1890 (12.2%),

and 2,046,828 by 1910 (9.8%) (Kann 1979, 605-8).

With significant Danube Swabian populations in Hungary's main

urban centres, this made them very disproportionately powerful

for an immigrant community. Despite the problematic franchise

struggle between Hungarians and German settlers, the Danube

Swabians considered Hungary as much their homeland as the

Germany that they left behind. They rapidly became integral

parts of Hungarian civilisation and statecraft, a feature

that endured until their expulsions out of Hungary and 'back'

to Germany after living in Hungary for centuries.

(source: stefan-jaeger.net)

(source: stefan-jaeger.net)

(source

danubeculturalsociety.com)

(source: schlarb.com)

The political

and cultural relationship between Hungary and the Germans

changed with the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, when the significant

Hungarian population within the Habsburg Empire revolted against

the ethnic German political caste, seeking an equal royal

union between Hungary and German Austria that would give equity

to both peoples. The contumacy ended with the Ausgleich Compromise

of 1867, when Hungary was allotted a resplendent parliament,

a legal corpus, its own limited army (the Honvédség), near-equal

ethnic rights within the empire, and the formation of a superficial

dual monarchy as the kingdom of Austria-Hungary. Afterward,

the Magyars (Hungarians) initiated a nationalistic campaign

of 'Magyarisation' that worked to stymie the influence of

the sizable German, Serb, and Romanian minorities and aggregate

political preeminence to the Hungarians. The German language

and their pronounced cultural autonomy were diminished, and

assimilation was actively pressured. The Danube Swabians,

considering Hungary to be their home, adapted magnificently.

Many Magyarised their names, learned Hungarian, and counted

themselves on statistics as being Hungarian nationals (although

most retained their German identity and language in the private

realm). For example, the population of Buda in 1869 (just

after the Compromise) was 54% German, only 34% by 1880, and

23% by 1900 (Heiszler 2002, 48). Although Buda and

Pest were increasingly becoming major cultural centres and

thus endured legitimate ethnic Hungarian immigration, this

steady 'reduction' of the Danube Swabian population was also

largely a result of superficial and highly pragmatic assimilation.

Some 600,000 Germans declared themselves to be Hungarian nationals

on the subsequent censuses from 1880 to 1910, rather than

their previous status as being foreign nationals (Lendvai

2004, 328). A period of cultural exchange and flourishing

appeared in Hungary between the semi-Magyarised Swabians and

the Hungarians that manifested in linguistic, cultural, and

architectural features. For example, even today, many Germans

in Hungary use blatant Hungarian grammatical injunctions,

such as the Hungarian 'sz' for the German 's' sound, and the

Hungarian 's' for the German 'sch'. Many surnames in Austria

today demonstrate Hungarian and German name roots as a result

of the shared Habsburg legacy and the expulsion of most Danube

Swabians to Austria and Germany. Due to their prudent adaptation

to a changing Hungarian society, the Swabians were able to

retain most of their economic and political prominence even

during the campaigns of assimilation.

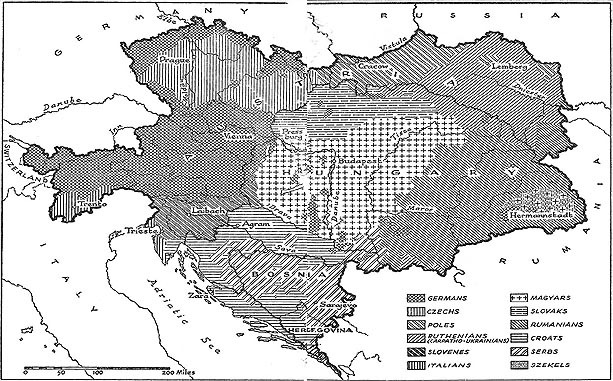

A

map of the Habsburg Empire. Devote close attention to the

cross-marked areas in Hungary and its periphery, denoting

German settlers. (scanned

from Kann).

CLICK MAP FOR ENLARGEMENT

The Danube Swabians retained their ethnocultural and sub-national identity even until the dissolution of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1918. An eclectic variety of German-speaking student groups, intelligentsia circles, gymnastics assocations, and political parties operated with the ulteriour design to represent the Danube Swabians as a whole. The Association of German Students in the Lands of the Hungarian Crown (founded in 1899) and the Hungary German People's Party of 1905 cooperated with student groups like 'Suevia Pannonica', 'Gothia', and 'Langobardia' under renowned social personalities like Edmund Steinacker, Adam Müller-Guttenbrunn, and Jakob Bleyer. Although the Hungarians did not recognise the Danube Swabians as a sub-national political body, earlier legal measures against the use of German were gradually assuaged by the early 20th century. Of the 22 daily newspapers in Budapest by the fall of the kingdom, 5 were published in German (including the 'German Daily for Hungary'), illustrating a prudent adaptation of the Swabians to the Hungarian struggle for franchise within the empire (Lendvai 2004, 328).

The relationship between Danube Swabians and Hungarians changed again with the fall of the Habsburg Empire in 1918 upon the close of World War I. At the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, the Western Allies officially forced Hungary to forfeit nearly 70% of the crownlands they had ruled for nearly 1,000 years, leading to the independence of Slovakia and Croatia. Transylvania, with its large German population, was given to Romania. The Banat and Vojvodina regions, and thus the Banat Swabian population, was transferred from Hungary and divided between Yugoslavia and Romania. Hungary proper was shorn of more than 30% of its territory (Burleigh 2001, 49). As a result of the treaty, significant Danube Swabian minorities now were transferred from Hungary to what soon became Yugoslavia, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. Therefore, the independent nation of Hungary lost a tremendous Danube Swabian statistic within its borders. Whereas there were roughly 2,046,828 Danube Swabians in all Hungarian crown lands in 1910, there were only 550,000 in Hungary proper by 1920, or 6.9% of the population (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). So too, nearly 200,000 Danube Swabians had emigrated out of Hungary from 1880 to 1910 in reaction to fiscal and political tumult (ibid).

After Hungary defeated the coup of the anarchist Hungarian Soviet Republic, the ultra-nationalist regent Miklós Horthy established a Fascist state that forged a longstanding alliance with Adolf Hitler until near the end of World War II. The Horthy regime espoused the primacy of the Hungarian language and culture to the detriment of the smaller minorities. A policy of assimilation pressured the Swabians to forego their academic associations and fully integrate into Hungarian society. This reinvigourated Magyarisation policy worsened inter-ethnic tension, since the previous participation the Swabians enjoyed in the Hungarian Parliament had been eliminated by Horthy's authoritarian status. At the same time, the pan-Germanic nationalism and racialism that had swept Germany and Austria under Adolf Hitler galvanised the Danube Swabians to adhere to far-right movements that directly addressed their community interests. This exacerbated the conflict between the Hungarian nationalists and the Swabian minority. Joseph Goebbels, the Propaganda Minister of the Third Reich, described in typical National Socialist parlance a greatly exaggerated perception of supposed 'oppression' of the German race by Hungarians, writing in his diary that he '...received reports about the fate of the German minorities in Hungary. The Hungarians still dare to commit acts of effrontery towards us that go far beyond what we can stand for...we must keep quiet for the moment. We are dependent upon them' (Goebbels 1948, 112). The most salient far-right and pan-Germanic movement in Hungary was the Volksbund der Deutschen in Ungarn (People's Union of Germans in Hungary). Led by Franz Anton Basch, the party adopted an ideology of pan-Germanic racialism and sought either repatriation or direct incorporation into the Third Reich similar to the Sudeten Germans of Czechoslovakia.

Although the friction between Hungarian and German nationalist elements in Hungary was a recurring problem, it is often grossly overstated. Assimilated Danube Swabians retained influential political status throughout the period of Hungarian authoritarianism. Even the Hungarian nationalist Prime Minister of Fascist Hungary from 1932-36, Gyula Gömbös, was an assimilated Swabian (Spannenberger 2005, 85). The presence of pan-Germanist movements among Danube Swabians does not equate to a direct rejection of the Hungarian state nor the charismatic regime of Miklós Horthy. Most Swabians still considered Hungary to be their home even if their ideology focused on German cultural interests. So too, the secondary status of Hungary within the Axis, as well as its dependency upon the Third Reich for military and economic survival, meant that the Swabian minority enjoyed significant protection under German pressure. For example, when Hungary acquired Transylvania from Romania, the large German population was formally represented by the political lobby of the Hungarian Volksbund when Hitler appointed its leader the head protector of all Danube Swabians. Further, when Germany, Hungary, and Bulgaria carved up Yugoslavia in 1940, the Banat territory straddling Hungary and Serbia was elevated to an autonomous province, and its Danube Swabian minority was afforded significant control despite being only 20% of the population and being intently claimed by Hungary (Hrvatski Informativni Centar). Political considerations worked in favour of Hungary's Germans. Lastly, Hungarian nationalism primarily revolved around the Hungarian culture and the state, rather than race. Therefore, the Swabians were not overtly subjugated so long as they did not reject the the primacy of the nation that they considered home. It was only after the 1944 deposition of an armistice-seeking Miklós Horthy and his replacement by the extreme-right Arrow Cross government that Hungarian nationalism focused on the racial qualities of the nation. Even during the ideological assertions of racially pure 'Hungaricism' after 1944, the Danube Swabians were still not an oppressed or second-class minority because Hungary was totally dependent on Germany as a puppet government. Since their settlement in their new homeland over two centuries ago, the Danube Swabians were remarkably able to adapt to the evolution of Hungarian society.

By the summer of 1945, the Soviet Red Army had obliterated the Third Reich and its allies of Hungary and Romania. The southern marches of Hungary were forcibly given to Yugoslavia, whilst Transylvania and its large ethnic German population were awarded to the new Communist state of Romania. Due to Hungary's strategic significance and its location between the Western and Soviet orbits, the administration of Hungary was vastly controlled by the joint Allied Control Commission. As a result, the stifled independence of Hungary meant that the expulsion of Germans ordered by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference was exerted directly. Whereas Czechoslovakia independently expelled over 3,000,000 Sudeten German civilians, the removal of the Danube Swabians in Hungary was performed under direct Allied observation. The expulsion programmes were carried out by the cooperation of the Americans, the Soviets, and a sometimes reticent Hungarian Communist government.

In the Potsdam Conference of 1945, the Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain agreed that 'the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, will have to be undertaken.' Hungary's Swabian German community – an integral constituent in the cultural and national evolution of the Hungarian nation for centuries – was to be completely removed, ideally in as humane and expedient a process as possible. The expulsion of Hungary's Germans was far more politically complicated than those performed in Czechoslovakia and Poland. Unlike the Czechs, Poles, and Soviets, the Hungarians themselves were reluctant to accept the concept of collective guilt, whereby all persons of German ethnic identity were universally generalised as proponents of Nazism and genocide. This political stance was in part beneficial for the Hungarians themselves, since they had actively participated with the Third Reich on both the western and eastern fronts throughout the war. By diverting blame for war-time atrocities off of the Germans and Hungarians and onto deposed dictatorships, the Hungarians were in additionally protecting themselves from crippling indemnity and restitution. So too, the initially reticent and passive policy of the Hungarian government was in the context of the expulsion of Hungarian civilians from Slovakia by the Czechoslovak government. At least 40,000 ethnic Hungarians were forcibly removed along with more than 3,000,000 Sudeten Germans, and expelled to occupied Hungary (Migration Citizenship Education). By rejecting the concept of collective cultural responsibility, the Hungarian government was ostensibly safeguarding the Hungarian minorities in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia from feared persecution. The Hungarians were also concerned about removing a significant productive minority from the labour force during a time of complete economic ruin and rampant unemployment.

Despite

the Hungarians' initial reluctance, the legitimate military

and political authority in Hungary was the joint control of

the Allied Control Commission. Although the Soviets had orchestrated

the conversion of Hungary into the Communist Hungarian People's

Republic under Mátyás Rákosi, the de facto controllers of

Hungary during the time of the expulsions (1945-48) were the

United States and the Soviet Union (Apor, 2004, 35).

The Danube Swabian community was to be removed from Hungary

regardless of the compunction of the Rákosi government.

Churchill, Truman, and Stalin meet at the Potsdam Conference

that initiated the formalised expulsions

Matyas Rakosi, the Communist leader of Hungary

Attempting to calculate the total number of expelled Danube Swabians is incredibly difficult due to a variety of factors. There is no available census information on the demographics of Hungary in 1945. The last official government statistics date from 1941, citing 511,672 total ethnic Germans in Hungary, or 5.1% of the population (Központi Statisztikai Hivatal 2). However, this statistic includes the tens of thousands of German residents that Hungary inherited when Transylvania was annexed in 1940. The official statistic of the Horthy government for Transylvania in 1941 cites roughly 44,600 Germans. Many sources estimate about 477,000 Danube Swabians in Hungary proper in 1941. Therefore, Hungary at the time of the expulsions after 1945 had at least 470,000 or ~5.1% (Landsmannschaft der Deutschen aus Ungarn). What is certain is that the official population of Danube Swabians in Hungary dropped from at least 477,000 (5.1%) in 1940 to only 22,455 (0.2%) by 1949, the complete depletion of more than 95% of an ethnic community through expulsion, forced labour, and involuntary displacement (Gall 1993, 343, WHKMLA). At least 130-200,000 German civilians were recorded as being directly shipped from their homes to the border of occupied Germany by train (Apor 2004, 35). The statistical logs on German families expelled by train do not fully reflect the total number (all but 22,455) who were ultimately displaced as fleeing refugees, nor the number of those who were deported and gaoled as political prisoners in the USSR. Importantly, only a small percentage of the Danube Swabians who disappeared from the Hungarian census by 1949 fled voluntarily. One credible source from the BBC calculates that the number of Danube Swabians who fled or were evacuated by the Volksbund before the end of the war was only 3% of the pre-war German population, and 60,000 total to avoid imprisonment thereafter (Wassertstein). This dictates that the vast majority of the 400,000+ Danube Swabians who disappeared from Hungary by 1949 were a result of direct displacement and expulsion rather than voluntary war-time departure. The largely outdated official report by the West German government from 1958 cites 597,000 Germans expelled from Hungary, 259,000 who were forced to flee, and 53,000 dead due to starvation and ethnic violence (SBD 1958). This inflammatory conclusion has been largely dismissed in historiography, especially since it claimed that more Germans were expelled than even existed in Hungary. The official Hungarian government statistics bureau reports a total loss of 188,081 Danube Swabians, of whom only 21,147 were expelled directly by the Hungarian government and 36,827 were gaoled before or after expulsion (Központi Statisztikai Hivatal 2). These statistical disputes notwithstanding, an entire ethnic community was ultimately lost in less than 5 years. Nonetheless, the expulsion of Hungary's Germans was very mild compared with that of other German populations due to the reticence of the Hungarian government and the spontaneous refusal of the American commissioners to compound the problem of at least 400,000 German refugees.

The expulsion of the Danube Swabians from Hungary occurred in several phases. The first was, quite appropriately, against Nazi and Arrow Cross war criminals who caused the Jewish community to almost be extinguished. By some estimates 600,000 total residents of Hungary and at least 40-65,000 Germans were arrested by the Red Army for their alleged participation with the Hungarian Arrow Cross Nazi movement or the German Volksbund. Quite rightfully, most of the prominent participants in war-time atrocities against Jews and especially Communists were executed, including Arrow Cross leader Ferenc Szálasi and the Volksbund chief Franz Basch. Although full-scale deportations did not begin until January of 1946, departures, imprisonment, and executions were rampant following the Soviet annexation of Hungary at the end of the war. In 1945, Lavrenti Beria, the head of the Soviet secret police (NKVD), reported that 23,707 Germans and Hungarians had been arrested or executed due to accusations of Nazi collaboration or far-right ideological affiliations (Mevius 2005, 57). The majority of those arrested were deported to the Soviet Union, primarily to gulags in Siberia and the wastelands of Kazakhstan along with 400,000 Volga Germans. At least 40,000 Swabians were deported to the USSR for forced labour, and 50% never returned (Mevius 2005, 57). As many as 70,000 total Hungarian and German residents of Hungary fled in the initial Soviet advance, and are therefore not counted in the total number of displaced Danube Swabians (Apor 2004, 38). More than ten thousand Swabians are suggested to have been evacuated at the end of the war by the German and Hungarian governments in prediction of Soviet reprisals (Burleigh 2001, 595). As a result, the drastically reduced statistics of the total numbers expelled do not take into account the families imprisoned or forced to flee their homes. Their degrees of cooperation or support for Fascism, if at all, remains unknown in historiography. It is certain that a large number of those arrested and executed by the Soviets before 1946 were legitimate war criminals. Although there were thousands of Hungarians and Swabians who volunteered for the Hungarian Honvédség or the Waffen-SS, many civilians gradually developed diverse political beliefs as the Axis neared its inevitable defeat. One prominent Hungarian researcher from the timeframe calculated that at most 250,000 could be tried for even limited connections with Nazism or Hungarian ultranationalism, meaning that hundreds of thousands were unnecessary displaced along with a large number of that 250,000 who may have been innocent (Kertesz 1953, 191).

The second phase of expulsions began in January of 1946, and was organised to completely remove the entirety of the Danube Swabian community from Hungary. Whereas the first phase had admittedly purged Hungary of thousands of horrendous war criminals and Waffen-SS murderers, the expulsions of 1946-48 targeted the remainder of the civilian population altogether. The Allied Control Commission was goated by the Soviet commanders Voroshilov and Sviridov to expel at least 500,000 Danube Swabians immediately (Kertesz 1953, 188). As this was more than the total number of Germans in Hungary, it is evident that the whole community was to be liquidated solely on generalised ethnic grounds that fancifully depicted all German people as inherently pro-Nazi proponents of atrocities.

General Sviridov famously responded to inquiring American ACC representatives with the lamentation, 'two families are living in your farm or your house, and therefore it has two residents. And so long as the Swabian sits in your house, the Hungarian lives in the barn' (MTA Jelenkor-kutató bizottság 2000, 456). Their Hungarian citizenships were revoked, rendering them as refugees who were unable to vote or seek state services (Apor 2004, 39). Those with German names (even ethnic Hungarians) were included. All German property was to be confiscated and annexed to the state. The Hungarian government intended to transfer the depopulated homes and farm land from German families to the tens of thousands of resettled Hungarians who were expelled from Czechoslovakia. 693,276 acres (more than 280,558 hectares) were seized directly from German families, including farms that their ancestors had maintained for over a hundred years. This was 1/8 of all land that was redistributed by the Communists to the Hungarian peasants under the Rákosi government (Mevius 2005, 117). This land and property redistribution noticeably hurt the Hungarian economy since it depleted a productive minority from the economy (Magyar Forradalom Történetének). Hungarian General Secretary Mátyás Rákosi encouraged to the Allies that the property confiscations and the transfer to Hungarians should only occur in towns with Hungarian majorities. As a result, it was tacitly intended that overwhelmingly German towns would not be completely depopulated and given to Hungarian settlers. This was in keeping with the Allies' admonitions to make the expulsions as humane and orderly as possible.

However, other powerful Hungarian Communist lobbies, such as the National Peasant Party of the anti-German Imre Kovács pressured for a sweeping removal of all Danube Swabians immediately: '...the Swabians cut themselves off from the body of the country, and with all their actions proved that they felt one and the same with Hitlerite Germany. Now they can share in Germany's defeat...Every Swabian is a [Nazi] Volksbundist'. Even the more moderate Rákosi eventually folded to Allied, Soviet, and activist pressure and promised the 'liberation from the Germanisation of the country' (Mevius 2005, 141). The sweeping generalisation of German-speaking residents as far-right traitors to the state ignores the centuries of active membership of the Danube Swabians in Hungarian society, as well as the fact that Hungarians themselves had been one of Hitlerite Germany's closest allies throughout the war. Nonetheless, the policy of the Hungarian government towards the German question was far more clement than in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the USSR. Thereoretically, those Danube Swabians who were actively lionised for anti-Fascist heroism, those married to Hungarians, those openly willing to abandon their German roots and attempt assimilation, and those deemed crucial for mining and industrial labour were sometimes eligible for exemption. Despite these partial limitations, the Communist party even knew that in several Danube Swabian towns as many as 80% had voted for the Marxists. Ultimately, even these anti-Nazi pro-Communists were to be removed (Mevius 2005, 141). So too, the Hungarian government insisted to the Allies that at most only 10% of residents of Danube Swabian towns could be exempted from expulsion, meaning that even if 90% of a village were innocent of Nazi associations, they would be expelled as well (Apor 2004, 41).

(source: BBC)

(source: stefan-jaeger.net)

Danube Swabians being escorted by a Red Army soldier (source:

stefan-jaeger.net)

The Danube Swabians were removed from their homes by soldiers and volunteers, and escorted to train lines and truck convoys to be sent to the German borders. At least 130,000 direct shipments of families are recorded in the first phase to the American zone, especially in Austria, Bavaria, Baden-Württemburg, and Hessen. Right behind them, some 130,000+ displaced Hungarians were resettled (Magyar Forradalom Történetének). The total families transported by train numbered in the thousands daily (Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden). In a few cases, expelled Swabians attempted to emphasise their loyalty to the nation where their ancestors had lived for centuries by waving Hungarian flags, singing Hungarian folk songs, and writing slogans on the sides of trains (Wasserstein). Although this could easily have been a last-moment attempt to be exempted from forced removal, it must be remembered that the Danube Swabians considered Hungary as much their home as Germany. Their ancestors had settled in Hungary over 200 years ago and did not even see the reunification of Germany in 1871. Most were allowed to take a maximum of 80kg of clothing and 20kg of food to the trains. This sustenance was not provided to them; expellees who had insufficient food in this time of post-war bankruptcy were not fed. Nurses and emergency care are recorded in many cases, but the American commissioners of the occupied zone frequently complained about the 'poor condition' of expelled Danube Swabians who were not receiving adequate hydration, sustenance, or medical attention for disease and malady. They complained about the separation of family members and the completely destitute financial and physical condition of Swabians when they arrived in Germany and Austria. They additionally asked the Hungarian or Soviet governments to subsidise them with 500 Reichmarks per family (Apor 2004, 41-3). This never occurred. It has been estimated by one biased and unverified source that 6,000 expelled Swabians died as a result of starvation, ethnic violence, and disease (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). This is far less calamitous than the more than 400,000 other Germans who died during their expulsion from Poland and Czechoslovakia (Burleigh 2001, 799). It is uncertain how many Swabians, if any at all as a direct result, died during the removal.

Ultimately, after the at least 130,000 Swabians had been shipped on trains to the American zone in Germany since January of 1946, the organised expulsion programme was halted by an American intervention in late June 1947. The American administration was overwhelmed by the more than 10,000,000 German civilians expelled from Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, unable to provide them with adequate employment, sustenance, housing, and innoculation. After the end of the deportation to the American zone in West Germany, the expulsion campaign resumed expediently under Soviet direction. Since the Soviets administered the future East Germany outside of American control, the subsequent deported Swabians were to be shipped to Soviet-occupied Saxony and Brandenburg. Unlike in the expulsions to the American zone, these Swabians often endured forced labour, imprisonment, execution, and by some reports ethnic violence. Thousands of Swabians and Hungarians, generalised as potentially perfidious, were gaoled for years in internment camps in the remote steppes of northeastern Hungary, especially in Tiszalök and Kaszincbarcika. This was long after the criminals of the Fascist regimes had been executed and purged in 1945. Even after the expulsions officially ended in 1949, Danube Swabian families (including women and children) languished in prison and refugee camps for years under dubious conditions (Wasserstein). One unverified and potentially biased source calculates that over 65,000 Danube Swabians were deported to the USSR for forced labour in gulags, with 16,000 dying in custody due to starvation, exhaustion, and execution (Landsmannschaft). As the Cold War intensified, the United States vociferously derided the Soviet mistreatment of removed Swabians in Soviet custody. The American commissioners implored the Soviets 'to make more orderly and humane the inevitable expulsion of those Germans who still remained in Eastern Europe...[and] to open occupied [East] Germany to those who were faced with deportation to remote sub-Arctic territories of Soviet Russia, an equivalent of annihilation' (Kertesz 1953, 187). The fate of the German civilians from Hungary deported to the Soviet Union remains uncertain. It is documented that at least 35,000 Danube Swabians were forcibly relocated on trains to Saxony alone in 1947 with far worse conditions than the first phase of expulsion (Apor 2004, 45). Ultimately, at least 50,000 were expelled to East Germany at a rate of roughly 10,381 persons in only one month (Kenez 2006, 215).

For a day-to-day diary of a Hungarian German's forced labor in a Soviet mine in Ukraine during post-war reconstruction, read John Knodel's diary here.

The expulsions altogether formally ended in Octobre 1949 under the decree of the Hungarian government via Prime Ministerial Decree No. 4274/1949. The Rákosi government, previously under the de facto control of the Allied Control Commission and increasingly by the Soviets, gradually asserted itself as an increasingly autonomous Communist state. After more than two centuries, the Danube Swabian population had dropped from 477,000 (5.1%) to only 22,455 (0.2%) in less than 5 years (Gall 1993, 343) for a more than 90% total loss. On 25 March, 1950, the Hungarian government formally withdrew all repatriation and exile restrictions on the Swabians, allowing them to return to their homeland of Hungary from the territories within the Soviet orbit (Magyar Forradalom Történetének). The total number of Germans who returned to Hungary after the expulsion measures were lifted is uncertain. Many of the few Swabians who returned were from among the 50,000+ deported by the Soviets to East Germany during the last phase. Due to intensifying Cold War border restrictions, most of the more than 200,000 directly transported by trains to West Germany were not able to return, nor were most willing to leave the auspicious employment potential of West Germany for languishing Hungary. Some sources calculate that 230,000 individual Danube Swabians temporarily returned to see their homes in Hungary by the 1980's (Wasserstein, Country Studies). The official censuses totaled 50,765 Germans in 1960 (a return of nearly 30,000 Swabians after the expulsions) and 50,765 in 1960 (Gall 1993, 343). For the small remaining Swabian population, use of the German language was highly excoriated in academia, society, political discourse, and employment as subversive. Rather polemical and often exaggerated sources describe the Danube Swabian experience in Hungary from 1950 until the fall of Communism as the 'silent generation' due to the discouraged or supposedly stifled status of the German language. To this end, some sources portray that the drastic drop of the German population on censuses results in part from the fact that Germans were reluctant to admit their ethnic identity due to fears of confiscations, forced eviction, imprisonment, or expulsion (Ibid.). Ultimately, the German population of Hungary after the expulsions (22,455) would nearly double due to partial return immigration, the disillusionment of trying to live in a Germany that their ancestors had not seen for centuries, and the increasing willingness of ethnic Germans to admit their German ancestry on government statistics as Hungary became more liberal towards minority groups.

As of today, there are only 56,918 ethnic Germans in Hungary, some 0.57% of the population (Központi Statisztikai Hivatal 1). This gradual increase results from the auspicious commercial ties that Hungary now maintains with Germany as its largest trading partner. This is a drastic reduction from the more than 2,046,828 Germans within the entire Hungarian crown in 1910 (9.8%), or the at least 477,000 who lived in a truncated Hungary in 1945. Although the expulsion of Hungary's Germans was very mild compared with the removal of ethnic German in Poland and Czechoslovakia, the expulsion of the Danube Swabians dismantled a long-settled and integral community solely on generalised ethnic grounds.

Today, the German minourity in Hungary arguably enjoys greater cultural and linguistic representation than in any other nation. As Hungary gradually divorced itself from the Communist orbit, limitations on the German language and the rights of minority communities were assuaged. In 1995, a Minority Rights Management Commission was organised via election among Hungary's Germans that designated the Party of Self-Rule for Hungary Germans as the representative political and cultural lobby of the Danube Swabian community. The German language and Swabian villages are superficially protected under Hungarian politics as being semi-autonomous. A boundless array of private and academic websites, institutions, German-language newspapers, student groups, and libraries exist in Hungary and are formally acknowledged by universities and local government officials. See the bottom of this article for many salient examples. The Hungarian government officially admits and passively commemorates the expulsion of the Danube Swabian community from Hungary. The government statistics bureau even offers a day-by-day analysis of the deportation of German families on trains and thoroughly describes the ordeal (see link). There are public gatherings and commemorative presentations in Budapest and other major Hungarian cities almost annually. Others from the German minourity contribute to the recognition of their community through other means. Mrs. Klara Burghardt, author of Das Häuschen und das Mäuschen (The Cottage and the Mouse) and a schoolteacher and author of nearly thirty years in Hungary, publishes children's books for German-language education both to promote the German language and, in essence, to announce that the German minourity is still thriving in Hungary. Although primarily sponsoured by Danube Swabian representative and nationalist groups, the Swabian story additionally enjoys strong support from Hungarian academics, news anchors, laymen, and political officials (Ferenczi).

(article continues below photos)

Schoolteachers and authors like Klara Bernhardt of Hungary

write children's books in German to promote the German language

and declare that the German minourity is still present (CLICK

TO ENLARGE)

There are a number of international and local expellee interest groups emanating from Danube Swabian and Hungarian German diaspora communities, particularly in Germany, Canada, and the United States. The Association of the Danube Swabians in the USA, the United Donauschwaben of Milwaukee, the Danube Cultural Society, and other groups actively emphasize the history of expulsions in their frequent assemblies and cultural gatherings at universities, college campuses, local clubs, and in newspapers. In February of 2010, hundreds of scholars, survivors, researchers, donators, human rights representatives, and even diplomats and figures from the United Nations gathered in St. Louis, Missouri, to hold the first international assembly commemorating the expulsion of Germans (especially Danube Swabians). Called "The Forgotten Genocide," the two-day conference included a large art gallery, press interviews, roundtable academic discussions, survivors' recollections, and dozens of speakers from diverse fields and motivations. The Institute for Research of Expelled Germans was also represented, delivering a speech on the destroyed Volga German community. The unique event even caught the attention of newspapers and forums in Poland and Germany, with both critical and positive commentary.

(article continues below photos)

Writer and human rights representative Kearn Schemm speaks in St. Louis (see our YouTube Channel HERE for the remaining video segments).

Writer,

historian, and former Croatian diplomat Tomislav Sunić speaks

on the history of Germans in Central Europe at an academic

conference in St. Louis, Missouri (see our

YouTube Channel HERE for the remaining video segments).

NOTE that Mr. Sunić has been criticised as

a nationalist and a revisionist.

The art gallery of "The Forgotten Genocide" conference

in St. Louis, Missouri, February 2010 (CLICK

TO ENLARGE)

Another wall of "The Forgotten Genocide"

conference (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Apor, Balasz. "The expulsion of the German-speaking population from Hungary." From the publication "The expulsion of the 'German' communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War." Published for the European University Institute, Florence, Italy, 2004.

Burghardt, Klara. Das Häuschen und das Mäuschen. Nationale Lehrbuchverlag/Budapest, 2011. -a children's book written for German schools and lectures in Hungary

Burleigh, Michael. The Third Reich: A New History. Hill and Wang, 2001.

Country Studies. "Hungary - Minority Groups." http://countrystudies.us/hungary/50.htm.

Encyclopædia Britannica. "Hungary." http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/276730/Hungary.

Ferenczi, Harriett. "Vertreibung und Errinerungskultur. Teil III: Ungarn." http://www.dradio.de/dlf/sendungen/vertreibung/538283/.

Gal, Susan. "Diversity and Contestation in Linguistic Ideologies: German Speakers in Hungary." Language in Society, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Sep., 1993): 337-359.

Goebbels, Joseph. The Goebbels Diaries. Trans. by Lochner. Garden City, NY: Country Life Press, 1948.

Heiszler, Vilmos. "Ofen-Pesttöl Budapestig." Limes: Tudományos Szemle, Jan. 2002.

Hrvatski

Informativni Centar. "Medjunarodni znanstveni skup

'Jugoistocna Europa 1918.-1995.'" http://www.hic.hr/books/jugoistocna-europa/02tablice.htm.

Kann, Robert. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1974.

Kenez, Peter. Hungary from the Nazis to the Soviets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Kertesz, Stephen. "The Expulsion of the Germans from Hungary: A Study in Postwar Diplomacy." The Review of Politics, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Apr., 1953): 179-208.

Központi Statisztikai Hivatal. "Population census 2001." http://www.nepszamlalas.hu/eng/volumes/06/00/tabeng/1/load01_10_0.html.

Központi Statisztikai Hivatal. "Die Vertreibung der Ungarndeutschen und die Volkszählung 1941." http://www.nepszamlalas.hu/hun/egyeb/nemet/data/tablak_d.html.

Landsmannschaft der Deutschen aus Ungarn. "Die Vertreibung." http://www.ldu-online.de/4.html .

Lendvai, Paul. The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory and Defeat. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Lumans, Valdis. Himmler's Auxiliaries: the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe, 1933-1945. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Magyar Forradalom Történetének. "Hungarian society between 1945 and 1956." http://www.rev.hu/history_of_45/tanulm_tars/index.htm.

Marrus,

Michael Robert. The Unwanted: European Refugees from the

First World War through the Cold War.

Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2002.

Mevius,

Martin. Agents of Moscow: the Hungarian Communist Party

and the Origins of Socialist Patriotism, 1941-1953.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Migration Citizenship Education. "Ethnic cleansing in post-World War II Czechoslovakia: the presidential decrees of Edvard Benes, 1945-1948." http://www.migrationeducation.org/15.1.html?&rid=14&cHash=837b8c7ccb.

Molnar, Miklós and Magyar, Anna. A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

MTA Jelenkor-kutató bizottság. "Documents the Meetings of the Allied Control Commission for Hungary 1945-1947." Budapest, 2000.

Sächsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden. Abt. Einbürgerung, 16 March, 1949.

Spannenberger, Norbert. Der Volksbund der Deutschen in Ungarn 1938-1945 unter Horthy und Hitler. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2005.

Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschlands (SBD). "Die deutschen Vertriebungsverluste" (1958).

Ungarndeutsche.de. "Geschichte der Ungarndeutschen." http://www.ungarndeutsche.de/de/cms/uploads/Geschichte%20der%20Ungarndeutschen.pdf.

Wasserstein, Bernard. "European refugee movements after World War II." http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/refugees_02.shtml.

WHKMLA. "Hungary: Demographic History." http://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eceurope/hundemography.html.

Zentrum gegen Vertreibung. "History of the German expellees and their homelands." http://www.z-g-v.de/english/aktuelles/?id=56.

Suggested reference: "The Jews and synagogues of Hungary, and their disappearance under the Hungarian Arrow Cross Nazi regime." From the European Heritage Library. Click here.

The Hungarian government's town-by-town analysis and statistics of the expulsion of German civilians, click here.

Toth, Agnes. Migrationen in Ungarn 1945-1948 (Migrations in Hungary 1945-48). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2001.

Bresser, Michael. The Danube Swabians: Biography of a People from Inception to Dispersal. Danube Swabian Association.

Spannenberger, Norbert. Der Volksbund der Deutschen in Ungarn 1938-1945 unter Horthy und Hitler. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2005.

1843- approximately 1,200,000 Germans in all lands of the Hungarian Crown (Croatia-Slavonia, Slovakia, Hungary) within the Habsburg orbit

1880- approximately 1,955,250 within the Hungarian crown territories, 12.5% of total crown population

1890- 2,116,578 (12.2%)

1900- 2,124,984 (11.1%). Around 200,000 ethnic Germans leave the Hungarian Kingdom to Canada, Western Europe, and America from 1899-1913.

1910- 2,046,828 (9.8%)

1920- after collapse of Austria-Hungary and the loss of more than 30% of Hungary's land (and thus her Danube Swabian populations to Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia), approximately 550,000 Germans in independent Hungary (6.9%)

1930- reduces to 480,000 (5.5%) due to post-war emigration and deaths in the Red-White civil war

1941- last available statistics before expulsions on Hungary's German population are from 1941, totaling at least 477,000 Danube Swabians (5.1%). The Hungarian government cites 511,672 (link). However, this includes the Germans of Transylvania, which Axis Hungary had obtained from Axis Romania in 1940.

1949- after expulsions, only 22,455 (0.2%) Germans in Hungary due to forced removal, fleeing, imprisonment, and emigration. This statistical difference from 1941 until 1949 does not consider the loss of Transylvania in 1945. According to Hungary's 1941 census of Transylvania, there were 44,600 Germans. Thus, this number disappeared from Hungary's German population not through expulsion. Instead, the Transylvania Saxons were expelled by Romania.

1960- 50,765 (0.5 %), an increase due to return immigration after the expulsion decrees were lifted in 1950. The increase is also partly explained by the increasing willingness of ethnic Germans in Hungary to acknowledge their German ancestry on official censuses, given the fact that fears of persecution have been assuaged.

2001- 56,918 Germans in Hungary today (0.57%).

Sources- [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], official Hungarian government censuses [6], Kann 1979, 605-7, and Gal 1993, 342.

Alexander Wekerle- 3-time and eventually the final prime minister of the Kingdom of Hungary within the Habsburg orbit before the empire's dissolution (1892-95, 1906-10, 1917-18)

Gustav Gratz- highly influential 19th-century writer, journalist, politician, and historian

Jakob Bleyer (1874-1933)- Hungary's minister of nationalities from 1919-20, and a major impetus for the German identity protection movement among student groups

Gyula Gömbös (1886-1936)- actually Julius Knöpfle, a highly assimiliated German who was Prime Minister of Hungary (1932-6) and an ultra-nationalist who supported dictator Miklós Horthy against the Communist regime of Bela Cohen (or Bela Kun) in 1918. He intently sponsored an alliance with Adolf Hitler. German origin collaborated by Spannenberger.

Franz Anton Basch- leader of the Volksbund der Deutschen in Ungarn, a far-right, pan-Germanist, and pro-Nazi party in Hungary that supported the Arrow Cross Hungarian Nazis and was one of the most rapidly expunged organisations after the Red Army triumph

Edmund Steinacker- important early 20th-century German-language student organiser in Hungary throughout the Hungarian crown lands (Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia)

Adam Müller-Guttenbrunn- worked with Edmund Steinacker to found significant student groups that other German identity representative bodies

Erika Ats- ebullient assimilated poet, died 1934

Georg Fath- poet and literature writer

Wilhelm Knabel- writer, publicist, and historian

Johann Weidlein- researcher and academic, died 1905

Suggested Websites and Organisations

Burghardt, Klara. Das Häuschen und das Mäuschen. Nationale Lehrbuchverlag/Budapest, 2011. -a children's book written for German schools and lectures in Hungary

Video Documentary: "Goodbye our Homeland!" (in Hungarian with English subtitles) - click here.

KlaraBurghardt.com - a German minourity author and schoolteacher in Hungary writing to promote the German language and acknowledge the enduring presence of Hungary's Germans

Das Portal der Ungarndeutschen (the Portal to the Hungary Germans) - click here. Huge database of information.

Landsmannschaft der Deutschen aus Ungarn (Community of the Germans from Hungary) - click here.

Landesselbstverwaltung der Ungarndeutschen (Organisation for Self-Government of Hungary Germans) - click here.

Vereinigung Ungarndeutscher Akademiker (Union of Hungary German Academics) - click here.

Ungarndeutsches Sozial- und Kulturwerk (Hungary German Social and Culture Works) - click here.

Landesverband der Donauschwaben, USA (Association of the Danube Swabians in USA, English and German)- click here.

Ungarndeutsche Bibliothek (Hungary German Library) - click here.

United Donauschwaben [Danube Swabians] of Milwaukee - click here.

Danube Cultural Society (English) - click here.

Landesverband der Donauschwaben, USA (Association of the Danube Swabians in USA, English and German)- click here.

StefanJaeger.net, an artist depicting the history and expulsion of Danube Swabians - click here.

Donauschwaben.hu - an online magazine for Danube Swabians (in Hungarian and German) - click here.

Paulus, Susanne, Pesic, Vesna and Cvejic, Marko. O podunavskim Shvabama/Ueber die Donauschwaben/About the Danube Swabians. Mandragora Films and "Kikinda" Deutscher Verein, 2014.

Cvejic, Marko. "The Silent One." DVD, Mandragora Films, 2011. Order here: http://www.mandragorafilm.com/#/en/naruci

Cvejic, Marko. " Danube Swabians." DVD, Mandragora Films, 2011. Order here: http://www.mandragorafilm.com/#/en/naruci

Mandragora Films, a Serbian-led initiative to document the Danube Swabian lost legacy -- click here.