Displaced Communities

![]() BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

displaced by Hitler & Stalin; 95%+)

![]() GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

(over 200,000 expelled, imprisoned, displaced, emigrated; 98.5% total)

![]() VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

![]() DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

15% of German population)

![]() GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

(100-200,000 expelled after WWI)

![]() GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

(over 3,000,000 expelled

and displaced; 95% total)

![]() GERMANS OF HUNGARY

GERMANS OF HUNGARY

(over 100,000 expelled, over

300,000 displaced; 88% of total)

![]() GERMANS OF ROMANIA

GERMANS OF ROMANIA

(over 700,000 or 91.5% displaced by Hitler, USSR, & emigration)

![]() US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

(10,906+ interned & blacklisted) NEW!

![]() GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

(over 5,000,000 expelled and displaced, nearly 100%) COMING SOON

![]() GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

(nearly 1,000,000 to Germany and Kazakhstan) COMING SOON

Other Information

![]() OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

(documentaries, interviews, speeches)

![]() Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

(for updates, events, announcements)

![]() "Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

"Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

![]() "British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

"British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

![]() "British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

"British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

![]() From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

(memoir about wartime flight & Jewish, Polish, & German daily life near Auschwitz) NEW!

![]() Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

![]() The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

![]() Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

![]() Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

![]() Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

![]() Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

![]() Suggested Resources & Organisations

Suggested Resources & Organisations

![]() In Memoriam: Your Expellee

In Memoriam: Your Expellee

Relatives & Survivors

![]() Submit content and information

Submit content and information

![]() How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

the Baltic German community destroyed by hitler and stalin's non-aggression pact

![]() Print this Article •

Font Size: -

+ •

Print this Article •

Font Size: -

+ •

![]() Send

this Article to a Friend

Send

this Article to a Friend

HOW TO CITE THIS SCHOLARLY ESSAY: Institute for Research of Expelled Germans. "The Baltic German community destroyed under Hitler and Stalin's non-aggression pact." http://expelledgermans.org/balticgermans.htm (accessed Day-Month-Year).

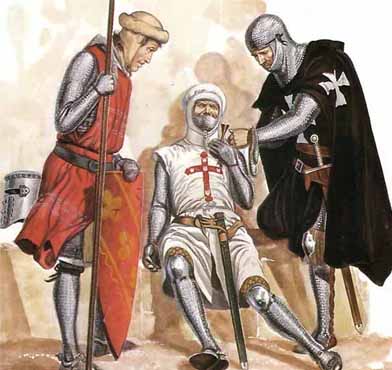

The Livonian

Sword Brethren (left) and the Knights of the Teutonic Order

(right), two German crusading orders who built the Baltic's

capitals

Included German minourity groups in this region: Baltic Germans, Latvian Germans, Memelland Germans

Total population change resulting from expulsion and forced resettlement: from 142,324 in all Baltic states to almost zero

_______________________________________

![]() History of Settlement and Culture

History of Settlement and Culture

![]() History of Expulsion

History of Expulsion

![]() Sources/Bibliography

Sources/Bibliography

![]() Population

Statistics

Population

Statistics

![]() Famous Persons

Famous Persons

![]() Suggested

Websites and Organisations

Suggested

Websites and Organisations

_______________________________________

History of Settlement and Culture

The first phase of ethnic German diasporic settlement abroad came with the Northern Crusades of the 13th century. As one of Europe's most politically and militarily salient Christian empires, the German Empire participated heavily in sponsoring German crusading orders and military legions to Christianize the last pagan regions of Europe. The Balts of Old Prussia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Finns in Finland and Estonia were among the last European peoples to be baptised. The most significant German crusading orders were the Livonian Brothers of the Sword (Schwertbrüderorden) and the Teutonic Order, known in German as the German Order (deutscher Orden). During these crusades, the pagan tribes of Latvia and Estonia were subdued and superficially converted by brute force, and Estonia became part of Denmark and Latvia was absorbed into the Livonian Order theocratic state. Subsequently, missionaries, tradesmen, and crusading knights from Germany, Denmark, and Sweden settled along the Baltic coastline and established flourishing trade cities. In 1201, Bishop Albert von Buxhöveden founded Riga, one of the Baltic's most historically resplendent ports and the modern capital of Latvia. Reval, the capital of modern Estonia (as Tallinn) was also founded by these German and Scandinavian settlers.

The German Empire had also sponsored the Teutonic Order, which rapidly forged a powerful theocratic chilvarous state stretching from eastern Germany to Prussia, to western Lithuania, to Latvia, and the eastern islands of Sweden and Finland called the Teutonic Order Monastic State. Eastern Lithuania (the independent Lithuania) was never absorbed. By 1236, the Livonian Order (and thus nearly all Latvia and much of Estonia) merged into the Teutonic knights' realm. At the same time, Denmark sold all of Estonia to the Monastic State under German auspices. The Monastic State paid tribute to Germany, and functioned as a de facto province of the Holy Roman Empire.

The ethnic German settlers in the Baltic – hence known as Baltic Germans (Baltendeustsche) – operated as the ruling ethnic elite caste in Estonia, Latvia, and the coastal ports of German-ruled western Lithuania for the next 700 years. Despite the fact that the Baltic shifted between German, Polish, Swedish, and then Russian rule, the Baltic German businessmen, merchants, landowners, clergy, knights, nobles, and government officials remained in drastically disproportionate control. This contrasted greatly to the native Estonians, Latvians, and western Lithuanians, who lived as virtual second-class citizens and poor farmers in their own homelands. This inferior political franchise would last in most respects until the independence of these nations for the first time after 1917. The ethnic caste stratification was a source of enduring tension between the natives and the Baltic Germans. The native Balts and Finns retained many of their traditional pagan customs for many centuries after Christianization, which allowed them to represent their independent identity at the same time as it prevented them from thriving in the German Catholic stratum of upper society. A very small minourity of natives assimilated and intermarried with the Baltic Germans, adopting their language and German names.

The Baltic

Germans remained an incredibly small population in the Baltic

that overwhelmingly controlled its economies, generally to

the detriment of the natives. In the beginning of the 16th

century, there were about 15,000 Baltic Germans in Latvia

(5%) and 15,000 in Estonia (6%). By 1800, there were about

60,000 (only 7%) in Latvia and 47,000 in Estonia (5.3%). In

1897 (near the end of Russian rule), there were 120,191 in

Latvia (6%) and 34,500 in Estonia (3.5%) (Latvijas Instituts,

Eesti Instituut). That this small minourity owned virtually

all of the land of the Baltic was greatly despised by the

Baltic peoples. This was exacerbated by consistent settlement

of ethnic German farmers from Germany and even Ukraine settling

in Latvia and Estonia (15,000 between 1906-1914 alone) who

further ebbed away at the traditional farming communities

of the native Balts.

(source: http://www.conflicts.rem33.com/images/deut/drang.htm)

A

map of the Teutonic Order Monastic State and Baltic German

settlement (source: Atlas of World History by Black,

and http://www.conflicts.rem33.com/images/deut/drang.htm)

CLICK

MAP FOR ENLARGEMENT

The Baltic German merchants living on the Baltic coast created resplendent port cities with luminous architecture, artwork, universities, church structure, and medical and scientific achievements, and effectively created the academic, political, and national foundations of the future Baltic states. By 1285, Riga, Reval (Tallinn), Viljandi, Pärnu, and Dorpat (Tartu) were constituents of the German Hanseatic League (deutsche Hansa), an economic customs union of northern cities mostly dominated by German-speakers that became incredibly wealthy from the 14th to the 17th centuries. The Baltic German community retained the German language, Germanic culture, and strong adherence to Catholicism due to their citizenship of the Monastic State. The Baltic German dialect remained linguistically intelligible with the rest of the Germans despite their separation from Germany due to the continuous flow of merchants and settlers from Germany to the Baltic coast.

By 1400, the Baltic Germans and Prussian Germans within the Teutonic Order Monastic State dominated nearly all of the Baltic coastline. The rapid demise of the theocratic realm came with the increasing concupiscence and belligerence of the Grandmasters that threatened the growing empire of Poland-Lithuania. After the Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War (1409-11), the Battle of Grünwald, and the Thirteen Years' War, the Teutonic Order was obliterated. In 1525, the Teutonic Grandmaster Albert converted to Lutheranism. Having abandoned the Catholic doctrine of the crusading order, the Monastic State was forever dismantled, and most of the previous realm became a territory of Poland for at least two centuries. The overwhelming majourity of the Baltic Germans subsequently converted to Protestantism. The Baltic Germans, however, escaped Polish rule by declaring independence, and ruled Latvia and most of Estonia. The independent Baltic German polity ended after the Polish triumph against Russia in the Livonian Wars (1558-83). The Baltic Germans were ruled by Poland until Peter the Great incorporated all of the Baltic states into the Russian Empire after the Great Northern War (1700-21). The Baltic Germans remained under Russian rule until 1918, when they became part of independent Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia.

Despite the cyclic shift of political authority, the Baltic Germans remained the prime economic and ethnic caste in the Baltic. Poland, Sweden, and Russia each chose to keep the wealthy Baltic Germans in financial and political control of the region. When under Polish rule (16th-18th centuries), at least 1/3 of all Polish and Lithuanian exports came through Riga alone, a port city built by and vastly controlled by Baltic Germans (Derry 1979, 112). During the Swedish interlude in Estonia at the height of their imperial power, 21.1% of Sweden's income came from the Baltic German port cities of the Baltic (Derry 1972, 152). This auspicious relationship and the power of the Baltic Germans continued when transferred to Russian rule. The Baltic was Peter the Great's key to controlling the markets and navies of Northern Europe, and since Baltic Germans controlled its economies, they enjoyed great sponsorship during Russian rule. The Baltic Germans were even intermediaries and diplomats for the Russian government due to their loyalty to the Tsar. They remained in control of education, the Lutheran church, the wealthy estates, money, businesses, and political office (Ostler 2005, 433). By the end of Russian rule (until 1917), 22% of the Lutheran clergy in Lutheran-majourity Estonia and Latvia were Baltic Germans despite their small population (Eesti Instituut). They even dominated as much as 20% of the Russian political and economic bureaucracy as a whole in the 18th and 19th centuries (Ostler 2005, 439). The language of instruction at the thriving university on the Baltic, Dorpat University (today Tartu Unversity), was strictly German after 1802, and most of the faculty were ethnic Germans. Riga, the chief port for business and employment for Germans, Latvians, Russians, and Estonians alike on the Russian Baltic, was 42.9% German out of a population of 102,590 in 1867 (Latvijas Nacionalais Vestures Muzejs). Even by the end of Russian rule, when Russian nationalism had decreased German influence, 1,100 German land owning families alone owned 42% of Estonia's arable land. 90% of large estates in Estonia and 90% of businesses in the capital of Riga were owned by ethnic Germans (Hiden 2002, 36). While in general there was not much overt anti-German sentiment among the Balts, the inequality of wealth between Germans and indigenous peoples remained a factor in developing ideas of Baltic nationalism and assimilation after independence in 1919.

The ethnic imbalance changed with the assimilation policies of the Russian Empire and the modernisation of the Baltic states. With partial industrialisation in the Baltic in the 19th century, the Baltic's ethnic groups worked alongside each other in factories, leading to the introduction of a new working class of native Balts into employment markets, production, and intellectual centres. However, the German minourity remained disproportionately wealthy and powerful in the developing Baltic economies. At the same time, however, the intensifying trend of Russian nationalism led to the erosion of regional autonomy among ethnic minorities across the Russian Empire. The German academic and political institutions were Russified, and Lutheranism was eschewed. German newspapers were discouraged from using the German language. Dorpat (Tartu) University was now Russian. Old city councils previously dominated by Baltic Germans were replaced by elections or personal imperial selection. However, as with much of the Russian Empire, the Russocentric assimilation policies backfired in creating new secret nationalist societies and underground movements that pressured for Baltic independence.

With the end of World War I and the formation of independent Baltic states, the situation changed again for the Germans and the Baltic peoples. With the defeat of the Russian Empire in 1917 and the occupation of the Baltic by the German Empire, the coastal states declared their independence. The Baltic Germans collaborated greatly with the invading German armies, and sought to either merge with the Reich as an extended province of Prussia or establish independent Baltic German states that encompassed most of the Baltic. Adolf Friedrich Herzog von Meckenburg advocated a new government that included Kurland, parts of Estonia, Lettgalia, Oesel, Livonia, and Riga (Latvijas Instituts). This was to be a regime led by Baltic Germans but inclusive of Baltic peoples. For the most part, Baltic nationalists and Baltic German minourities worked together to defeat the invading Russian armies and the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War (1917-23).

It is important not to depict the historical relationship between Baltic Germans and the Baltic peoples as entirely amicable. Although even today there is little animosity between Latvians, Lithuanians, and Estonians for their former German minourity, many factions among the Baltic Germans played a direct role in undermining Baltic independence movements after 1917. Initially, Baltic Germans were anxious to work with the Balts for a Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania free of Russian rule. Each group had the shared goals of resisting a possible invasion by the growing Bolshevik movement or even an assault from irredentist "White Army " soldiers hoping to revive the Russian Empire. Since the German government was still fighting in World War I, Germany supported the re-establishment of an independent Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia -- but of course under German control. While Lithuanians were seizing the opportunity declare independence -- even going as far as to elect a German price as "Mindaugas II" in order to avoid direct German rule -- the German government soon clamped down on independence movements in the Baltic to maintain German influence.

At the same time, the German minourities realised that Baltic independence would strip the wealthy Baltic German upper class of their power. After Germany quit World War I, the Baltic Germans therefore lost their protection from both the Russians and from Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian nationalists. Now liberated from foreign occupation, the Baltic nations fully declared independence. In response, many among the Baltic German elite declared that the United Baltic Duchy and the Duchy of Kurland and Semigallia had full sovereignty over all 3 Baltic republics. The secessionist governments set up paramilitary militias (the baltische Landswehr) with support from former German soldiers (Freikorps) who now had no war to fight. Neither of these would-be nations called for official discrimination and welcomed Baltic peoples as citizens. The government's council included Latvians, Estonians, and Baltic Germans.

Adolf Friedrich von Mecklenburg, elected head of the United Baltic Duchy; formerly an administrator in the German colony of Togoland

As a result of this chain of events, many prominent Baltic Germans became a new faction in the Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian Wars of Independence against the Soviets, the White Armies, and Baltic Germans alike. By 1919, with no support from the German government, the United Baltic Duchy was essentially defeated by the Baltic nationalist armies. With their leadership arrested or exiled, the Baltic Germans were forced to accept citizenship in the new Baltic republics and assimilate. The overwhelming majourity of Baltic Germans did successfully integrate into the new states, but maintained a distinct German identity until their eventual expulsion after 1939.

In the regions of the Baltic states that were briefly occupied by Soviet troops during the Baltic Wars of Independence after 1918, the Bolshevik governments particularly targeted the Baltic German minourities because of their historic role as the economic elite and "bourgeoisie." Using emergency decrees, the brief socialist regimes targeting most Baltic Germans for arrest, executions (although rare), or deportation to the Soviet frontier in Central Asia in cooperation with the emerging Soviet Union. All wealthy families were subject to arrest without trial (Eestiajalugu). Tthese ephemeral socialist regimes collapsed along with the eventual Soviet defeat.

By 1920, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania were independent states. For the first time in 700 years, the native peoples were in control of their own homelands. The coastal portions of Lithuania (Memel), previously part of German Prussia, were taken from Germany by the Allies at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Eventually given to Lithuania, the Memel retained a large nationalistic Baltic German population. Much of the Lithuanian diaspora, the Lithuanian military, and the minourity in Memeland (Klaipeda in Lithuanian) rejected the German character of the region, emphasising its Slavic and Baltic heritage for several centuries before the Prussian monarchy even existed. Throughout the Baltic, the new governments greatly took the opportunity to abolish the 700-year German ethnic caste and aggregate economic and political control to the natives. The German population dropped due to war and exodus down to 18,300 (1.7%) in Estonia and 70,000 (4%) in Latvia. 20,000 Germans fled the Baltic to Germany with the retreating German army, where the German Weimar Republic considered the Baltic Germans to be citizens because of their blood (Hiden 2002, 55). The entire landed estate and manor system, long controlled by the Baltic Germans, was abolished. Much property was confiscated without compensation to the state or to native Baltic buyers at reduced rates.

The dictatorships of Konstantin Päts in Estonia (ruled 1938-40), Karlis Ulmanis in Latvia (1936-40) and Antanas Smetona (1926-40) in Lithuania imposed their own brands of nativist nationalism that diminished the cultural, political, and academic influence of the German minourity. German-language schools, institutions, and newspapers were barred or pressured to assimilate (Hosking 1992, 95). Since political offices were now elected and the Balts were in control, few Latvians or Estonians voted for German representatives. Germans usually won only six Saeima (parliament) seats in Latvia and two-to-four in the Estonian Riikogu (Zentrum gegen Vertriebung). Particularly after Lithuania lost its historical capital Vilnius to the wars of Polish expansionism, Lithuanian hostility towards minourities increased in a state of emergency. However, it would be inaccurate to say that Baltic Germans endured anywhere near the level of economic discrimination that the Sudeten Germans did in Czechoslovakia.

As a result of growing pressures of assimilation, the Baltic German communities were fragmented. Many formed splinter political groups calling for ethnic autonomy for the German minourity. Others, like Paul Schiemann in Latvia, worked to represent German interests in a liberal and cooperative bond with the Baltic states. Others took a radical approach and, through pan-Germanic racialist nationalism, were inspired by the Third Reich into National Socialism. Erhard Kröger was the most salient of the pan-Germanic Baltic German nationalists who eventually oversaw the expulsions of Germans in 1939 (see below). Rampant German nationalism under Kröger quickly became pervasive. Nonetheless, 80% of Baltic Germans in Latvia were fluent in Latvian despite the formation of over 150 Baltic German minourity interest groups (Latvija Instituts). It is important to understand that nationalism, paramilitarism, and mild forms of fascism were quite popular in the Baltic, particularly Latvia and Lithuania. Therefore, the growing popularity of National Socialism or radicalism among Baltic Germans should not imply that Baltic Germans sought to overthrow Baltic governments using any agenda of overt anti-Baltic racial nationalism. Nonetheless, the largely amicable relationship between the Baltic Germans and the Latvians, Estonians, and Lithuanians continued until the expulsions of the Baltic Germans after 1939.

By 1939, the political fate of the Baltic states was sealed due to the expansion of two massive belligerent hegemons, the Third Reich and the Soviet Union. The Baltic states, with their German minorities, were unfortunate victims stuck in the middle. In 1939, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin shocked the world by organising the antithetical partnership of non-aggression and friendship in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This was simultaneously the death sentence of the 800-year Baltic German culture and also the long-sought sovereignty of the Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. Unlike many other expulsions of ethnic Germans that were forcibly perpetrated by the USSR, Poland, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, the Baltic Germans were destroyed in many ways by Adolf Hitler himself. Finland, all of the Baltic states, Bessarabia (now Moldova), and eastern Poland were to pass into Soviet control without German intervention, and in exchange Germany would control western Poland and western Lithuania. Similarly to the diplomatic annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland, Germany had also annexed the coastal Lithuanian cities in the Memel region in 1938, at least 45.2% ethnic German with more than 64,024 highly pro-German citizens (worldstatesman.org). The Germans in this territory were not expelled until the Soviet conquest of Germany in 1945 because it was incorporated into the Reich directly.

In organising the resettlement of Baltic Germans into the Third Reich and in occupied Poland, governor Arthur Greiser insisted that "a return to the old homeland is out of the question" (Epstein, 174). The distinct heritage of the Baltic Germans was to merge with the mainstream identity of the pan-Germanic Reich.

Hitler

had effectively 'donated' the sovereignty of Estonia, Latvia,

and Lithuania to Soviet expansionism in order to pacify a

powerful enemy, weaken the Western Allies, and gain a free hand in western Poland and East-Central Europe (Weitz 1992,

212). The Baltic Germans had to either flee to Germany

or accept Communist rule. The Baltic states, however, had

no option but the forfeiture of their sovereignty. The reaction

of the Baltic German communities was indolent. The liberal

and cooperative Paul Schiemann in Latvia intently sought to

preserve the independence of Latvia and the autonomy of the

Baltic Germans within Latvia, and remained highly

respected. The majourity of the Baltic Germans, however, had

gravitated towards pan-Germanic nationalism and irredentism.

The most dominant German nationalist pundit was Erhard

Kröger, a straunch pan-Germanist. Kröger became the

spokesman of the Baltic Germans throughout most of the war.

With the Reich now extending to the border of Latvia (at Memel),

many Baltic Germans sought to escape Bolshevik rule and be

incorporated into German Prussia.

Erhard

Kröger, leading Baltic German nationalist politician who oversaw

the transfer of Baltic Germans, meets with German Propaganda

Minister Joseph Goebbels (cropped from axishistory.com)

Soviet and German foreign ministers Vyacheslav Molotov and

Joachim von Ribbentrop signing the non-aggression pact, with

Stalin at right

The dominant cultural and political ethos in Germany was racialist pan-Germanic nationalism that viewed all Germans of the world as constituents of the organic state of the Third Reich. The Baltic Germans were thus considered expatriat citizens of Germany. The German government promoted a campaign of 'Heim ins Reich' (come home to the Reich), describing Germany as the proper national homeland of the people of the German race in any nation. Although it is commonly asserted that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the forced removal of the Baltic Germans was proof that Hitler was only interested in his own power and not his ideology, the situation was far more complicated. Hitler felt that he was left with two options when approaching his Soviet foreign policy: allow Baltic Germans to fall under the purges and Sovietification of so-called 'Jewish Bolshevism', or force this tiny population to escape their supposed second-class status in the ethnic nationalist Baltic states.

The decision of forcing all Baltic Germans out of their homes, and the removal of an entire 800-year-old German culture in the Baltic, was merely a consequence for the well-being of the Baltic Germans in Hitler's mind. Admittedly, this decision was very politically convenient for Hitler himself. It also completely ignored the will of the Baltic German families who were forced to forfeit nearly all of their property and businesses that they had earned over dozens of generations. The expulsion and displacement of the Baltic Germans and Black Sea, Bessarabian and Volhynian Germans (all under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) was as much Hitler's fault as it was of any foreign hegemon.

As a result of Hitler and Stalin's political peace, the entire Baltic German community was to be completely transferred by ship, train, or truck out of Riga, Tallinn, and Memel. Most of these Baltic Germans were planned to be resettled in Germany proper and in German-occupied Poland in the province of Warthegau and Posen. Not only were to the Baltic peoples and the Baltic Germans to suffer, but hundreds of thousands of Poles were to be thrown out of their homes for new Baltic German settlers who were forcibly relocated. Germany's Aktion Tannenberg orchestrated the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Poles from the Polish Corridor and the Warthegau region for the resettled Germans, among them the Baltic Germans (Davies 2005, 330). See below for more information about the Baltic Germans in Poland.

The compulsory relocation of virtually all Baltic Germans occurred in several phases: 1) under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939; 2) when remaining Baltic Germans fled after the subsequent Soviet annexation in 1940 and; 3) when the Soviet Union conquered the Third Reich, its occupied Baltic states, and the Memel region in 1945 and either executed or expelled all remaining Germans. In 1939 during the time of peaceful transfer, there were about 13,700 Baltic Germans in Estonia and 51,000 in Latvia. The first phase was overseen by the leading Baltic German nationalist in Latvia Erhard Kröger, who supported Hitler's plan for all Baltic Germans to move to the Reich'. Between 1939 and 1940, more than 51,000 Germans left Latvia. Over 11,000 Germans chose to remain. When the Soviet Union occupied Latvia, 10,500 more Germans escaped. More than 60,000 total Germans fled Latvia from 1939 until 1941.

The expelled Baltic Germans were allowed to take up to 50 Estonian Kroon per person or the equivalent in Latvian Lats, and up to 500 Kroons worth in jewelry per person. Their property was either confiscated or sold at duty-free rates (Hosking 1992, 252). They were allowed to take their furniture with them or have it shipped to their new homes in Germany and Poland by the Soviet-occupied Baltic states after 1939 (Helmreich 1942, 711). The Baltic German Immigration Advisory Board, staffed by many Baltic Germans themselves, matriculated the relocated Baltic Germans with government subsidy and private support from German banks, and gave them citizenship cards after verifying their Germanic racial ancestry and identity. They received a high exchange rate when they exchanged their Kroons or Lats for German Reichsmarks (Helmreich 1942, 714). About a half-million ethnic Germans were resettled in total under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact from 1940-41 (Burleigh 2001, 448).

Baltic German families resettled under German and Soviet agreement (Source: eestiajalugu.ee)

By the time of the Nazi invasion of the USSR and the second occupation of the Baltic in 1941, only 1,500 Baltic Germans remained (Latvija Instituts). Kröger oversaw this 'repatriation' into the Reich of over 60,000 of Latvia's remaining Germans (Dwork 1996, 130). 15,000 Germans left Estonia at the same time (Deutschbaltische Gesellschaft). These resettled Baltic Germans were rapidly assimilated into mainstream German culture, and slowly most of the distict traces of the Baltic German dialect became extinct. Partly in response to what many saw as Germany's unfulfilled promises, some Baltic Germans hoped to return to the Baltic (even under Soviet occupation in some cases), but the German government in Berlin refused to allow Germans to fall victim to "racial contamination." At least 5,000 Baltic Germans died out of starvation, war, disease, and exersion during the forced transfer to the Nazi General Government in Poland (Eesti Instituut).

The vast majourity of Germans deported from the Baltic were resettled in German-occupied Poland and the Wartheland. As part of Generalplan Ost, the Wartheland region, like Ukraine, was to be converted into Germanised frontier lands for German farmers and industrialists. The indigenous Polish population was to be slowly removed or, in some cases, assimilated and Germanised through racial verification tests. To pave the way for Baltic German settlement (among others), at least 110,000 Poles, Jews, and other minourities were deported for slave labor or to temporary prison camps from the Zamosc region alone (see Zamosc). In total, more than a half-million Poles were displaced during German resettlement in Poland.

It is uncertain how many Poles died when they were expelled from their homes for resettled Germans. A total of some 436,000 relocated ethnic Germans (from Bessarabia, the Baltic, Poland, etc.) were to be resettled in Poland (Epstein, 2). 76,786 Baltic Germans arrived in Fall 1939 alone in the Wartheland region of occupied Poland (Łuczak, pod niemieckim jarzmem, 69-71). However, the great majourity of them only languished in subsidised German refugee camps in Poland, the Baltic, Austria, and Germany (Burleigh 2001, 581). According to some estimates, only about 500 residences were stolen from Poles and given to relocated Germans due to economic and logistical shortcomings. Over 250,000 German settlers remained on the waiting list to settle in Polish homes (Burlegh 2001, 596). However, it is most likely that far more Poles were displaced from there homes than we have records to verify. For more information on the fate of German settlers and Poles in Poland and Prussia, see our Germans of Poland article.

Despite the Baltic Germans' indirect participation in Nazi war crimes and the confiscation of Polish property, it is not appropriate to affix blame to the Baltic Germans themselves. As outlined above, most Baltic Germans were given no choice whether to remain in the Baltic or "go home to the Reich." In addition, most feared that they could not remain in the Baltic to face the supposed abuses of Soviet rule. As was evident in the brief Soviet occupation of the eastern Baltic in 1918, the Baltic Germans knew they would be the first target given their historic role as the bourgeoisie of the Baltic. Upon deportation, Baltic Germans were typically not informed where they would be settled, and were unlikely to know that they would be displacing Polish families. Nonetheless, as seen in the photo below, many of the resettled Germans did ultimately benefit from the expulsion of Poles.

This made it very easy for Poland to justify its expulsion of the entire resettled Baltic population to Germany after 1945 by accusing the entire ethnic group of personal involvement in Nazi war crimes.

Baltic Germans resettling in the homes of ethnic Poles who were themselves deported (Source: Bundesarchiv)

By 1941, after Germany violated the non-aggression pact with Russia that destroyed the Baltic German community, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania fell under the rule of the Third Reich. Most of East Prussia and the Baltic was under the superficial authority of Alfred Rosenberg, the chief philosopher and doctrinaire of German National Socialism and a Baltic German himself who was born in Russian Estonia. The Baltic peoples overwhelmingly supported the invading Germans, hoping to expel the Soviets and seize the chance for independence. German propaganda films like "G.P.U" or "The Red Terror" encouraged Balts to work with the occupying Germans to save the Baltic from the despotism, rape, and cruelty that were supposedly part and parcel with Soviet rule. In the film, a Baltic German woman's family is murdered by Soviet secret agents. She then devotes her life to revenge against the Soviet system before commiting suicide, which was intended to represent the hopelessness and sacrifice that Balts and Germans inevitably face under Soviet totalitarianism.

Upon "liberation" from Soviet rule, the German government maintained that it would support the establishment of semi-independent Baltic states under German protection. To this end, Baltic nationalists quickly established very unorganised councils to call for an autonomous or free Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. However, Balts were disappointed to learn that the German government shut down most of these nationalist movements when they were deemed to be too independent for German interests (Burleigh 2001, 535). The erosion of Baltic political independence intensified as the war on the Eastern Front turned against Germany. While many Baltic officials remained in power and worked with the German military, the Third Reich ultimately blocked the independence of the Baltic states and absorbed them into the territory of Reichskommisariat Ostland, which was administered as a military governate. The few remaining Baltic Germans, as well as the occupying soldiers, were predictably put in charge as the leading caste once again.

During Nazi occupation, some among what little remained of the German minourity worked closely with the many indigenous far-right groups in Latvia and Lithuania like the Thunder Cross, Latvian Legion, and Iron Wolves, who volunteered to assist the SS in carrying out the Holocaust. However, the overwhelming majourity of Germans who worked with native killing squads were soldiers from Germany and Austria, not the Baltic. After all, most of the Baltic Germans were already deported.

By 1945, the Soviet Union had re-conquered Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia from the Third Reich. The Soviets continued by purging, executing, or expelling all the remaining Baltic Germans as enemy collaborators and Fascists. Roughly 4% of Estonians and 2% of Latvians and Lithuanians were either executed or imprisoned during initial Soviet rule (Hosking 1999, 252). The surviving Baltic Germans were either executed or shipped on cattle cars by trains with almost no food, water, or sanitation for weeks to Siberia and Kazakhstan, where they joined the near entirety of the 1,084,828 other ethnic German Soviet citizens like the Volga Germans who were expelled solely because of their ethnicity (ibid). About 1 in 5 Germans in the Baltic died due to war, starvation, or execution under the Soviet expulsion. Around 40,000 Baltic Germans fled the Baltic and the refugee camps in Poland by 1945 and ultimately settled in West Germany. One of the most significant disasters of the war was the tragedy of the SS Wilhelm Gustloff, a civilian passenger boat ferrying away expellees and fleeing civilians (including escaping Baltic Germans) that was sunk by Soviet submarines, leaving at least 9,000 civilians and prisoners of war dead. In this last phase of the war, the entire German population of the Memelland in Lithuania was targeted. The Lithuanian port city, about 45.2% German when it was re-incorporated peacefully into Germany in 1938, was eventually given to the Lithuanian SSR. All of the over 64,024 Germans in Memel (Klaipeda) were expelled (worldstatesman.org), joining the more than 4,000,000 ethnic German civilians fleeing Prussia under Soviet and Polish direction after 1945. Most fled to West Germany, East Germany, Canada, Australia, or the UK.

Total calculations for the number of Baltic Germans expelled are uncertain. Well over 16,000 were removed from Estonia, 62,000 from Latvia, and 64,000 from Lithuania. The official German government statistics cite a total of about 256,000 German civilians forcibly removed from the Baltic, although this statistic has been criticised as outdated and likely exaggerated (SBD 1958). At least 150,000 were removed directly because of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Ultimately, an entire German cultural community was extinguished. The 800-year ethnic German presence in Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania was destroyed. The repatriated Baltic Germans were assimilated into the mainstream German culture of the Third Reich or the dominant Anglo culture of Canada, leading to the death of the ancient Baltic German dialect that is presently in its last generation (Illahie). Today, there are a number of Baltic German expellee groups in Germany that are sponsored or even subsidised by the German government, including the Deutschbaltische Gesellschaft and the Deutschbaltische Kulturstiftung. The fate of the Baltic Germans is a tragic one: an 800-year-old community was demolished in the interests of political diplomacy between two dictators who changed the history of the Baltic and the lives of its peoples in a whim with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939.

Burleigh, Michael. The Third Reich: A New History. Hill and Wang, 2001.

Davies, Norman. God's Playground: 1795 to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Derry, T.K. A History of Scandinavia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1979.

Deutsch-Baltische Gesellschaft. "Baltische Geschichte bis zur Umsiedlung 1939." http://www.deutschbalten.de/geschichte.html.

Dwork, Deborah and Jan van Pelt, Robert. Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present. New York: Norton, 1996.

Eesti Instituut. "Baltic Germans in Estonia." http://www.einst.ee/historic/society/baltic_germans.htm.

Epstein, Catherine. Model Nazi: Arthur Greiser and the Occupation of Wesern Poland . Oxford Univ Press, 2010.

Helmreich, E.C. " International Affairs: The Return of the Baltic Germans." The American Political Science Review, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Aug., 1942): 711-716.

Hiden, John. The Baltic States and Weimar Ostpolitik. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Hosking, Geoffrey. The First Socialist Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Illahie. "Baltic German - a dialect that is about to die." http://illahie.blogspot.com/2008/12/baltic-german-dialect-that-is-about-to.html.

James, David Smith. The Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Florence, KY: Routledge, 2002.

Jachomowski, Dirk. Die Umsiedlung der Bessarabien-, Bukowina- und Dobrudschadeutschen. Munich, Oldenbourg Verlag, 1984.

Latvijas Instituts. "Germans in Latvia." http://www.li.lv/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=78&lang=en.

Latvijas Nacionalais Vestures Muzejs. "History of the Museum." http://www.history-museum.lv/english/pages/par-mums/muzeja-vesture.php.

Łuczak, Czesław. Pod niemieckim jarzmem (Kraj Warty 1939-1945). Posen: PSO, 1996.

Nicholas, Lynn. Cruel World: Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011.

Ostler, Nicholas. Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. New York: HarperCollins 2005.

Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschlands (SBD). "Die deutschen Vertriebungsverluste" (1958).

Schechtman, Joseph. European Population Transfers: 1939-1945, Volume 1. Oxford University Press, 1946.

Weitz, John. Hitler's Diplomat: The Life and Times of Joachim von Ribbentrop. New York: Tichnor & Fields, 1992.

Worldstatesman.org. "Lithuania." http://www.worldstatesmen.org/Lithuania.htm#Memel%20Territory.

Eestiajalugu. http://www.eestiajalugu.ee/?event=Show_event&event_id=2483&layer=164&lang=eng#2483

Zentrum

gegen Vertreibung. "History of the German expellees and

their homelands."

http://www.z-g-v.de/english/aktuelles/?id=56#deutschbalt.

Zamosc. http://www.zamosc.pl/historia/historia.php?i=historia_m

Suggested references: "The Baltic Tragedy," a DVD movie documenting the Latvian, Estonian, Finnish, and Lithuanian struggle for independence against the Soviets that touches on the role of the Germans and the Nazis.

"History of the German Teutonic Order and their Legacy that shaped Eastern Europe for 800 years," from the European Heritage Library - click here.

Weitz, John. Hitler's Diplomat: Life and Times of Joachim von Ribbentrop. New York: Tichnor & Fields, 1992.

Von Nottbeck, Berend. 1001 Wort Baltisch - a study of words exclusive to the Baltic German dialect.

Statistics from the 13th to the 16th century are uncertain. Likely about 10,000 permanent settlers and large numbers of ephemeral German traders.

1550s- approximately 15,000 Baltic Germans in Estonia (~6%), about 15,000 in Latvia (~5%)

1690s- 20,000 in Estonia (~5%)

1881- 47,000 in Estonia (~5.3%). Around this time, about 60,000 in Latvia (7%)

1897- 34,500 in Estonia (~3.5%). 120,191 in Latvia (6%).

1920's- In 1922, 18,300 in Estonia (~1.7%). In 1925, about 70,000 in Latvia (4%).

1930's- In 1934, 16,300 in Estonia (~1.3%). By 1939 about 62,000 in Latvia (3.2%) before expulsion. About 64,024 Germans in Klaipeda/Memel (45.2%) by 1930.

1939- 13,700 Baltic Germans removed from Estonia and 51,000 from Latvia under Hitler's and Stalin's agreement.

1941- 7,000 Baltic Germans from Estonia and 10,500 flee Latvia to Germany and German-occupied Poland.

1945-50- All Baltic Germans are completely removed, and the few remaining after the defeat of the Third Reich in 1945 are executed or expelled by the USSR to Kazakhstan for collaboration. More than 40,000 living in Germany. All of the over 64,024 Germans living in Memel/Klaipeda (Lithuania) are expelled.

Sources- [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]

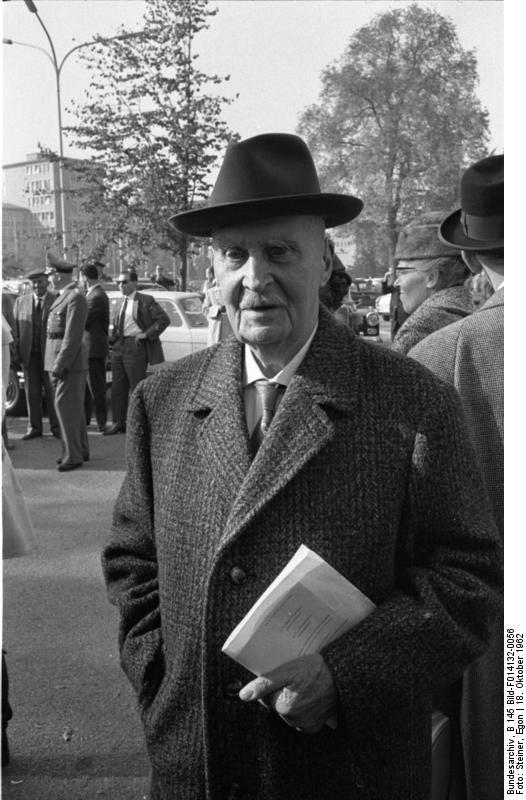

Alfred Rosenberg (1893-1946)- chief philosopher of the National Socialist movement of Germany. Extreme mystic, Ariosophist, and occultist, author of 'Myth of the 20th Century.' Executed by hanging after the Nuremberg Trials.

Bischoff Albert von Buxhövden (1165 †17.1.1229)- founder of Riga, one of the German missionaries/crusaders in Livonia.

Alexiy II, Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church (from Estonia)

Erhard Kröger- Baltic German leader and far-right pan-Germanist who sought to establish a Baltic German state merged with the Third Reich after the invasion of the USSR in 1941. Oversaw the expulsion of Baltic Germans into the Reich.

Paul Schiemann (1876-1944)- leading Baltic German politician in independent Latvia who led a very liberal policy and promoted autonomy and integration within Latvia. His liberal approach led to his increasing demise behind far-right and pan-Germanist parties like Erhard Kröger's.

Karl von Baer (1792-1876)- biologist and one of the founding figures of embryology

Kasper Dönhoff (1584-1646)- major diplomat fostering relations between Germany (Holy Roman Empire), Poland, etc.

August von Bielenstein (1778-1852)- significant military figure in Russia and one of the discoverers of Antarctica

Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz (1793-1831)- major figure in early zoology, biology, and science

Otto von Kotzebue (1787-1846)- one of Russia's and the world's greatest explorers and navigators

Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struwe (1793-1886)- famous astronomer

Peter Wrangel (1878-1928)- one of the leading commanders of the White Army against the Bolsheviks in the Civil War

Roman Ungern von Sternberg (1886-1921)- Russian general fighting for the White Army, becoming dictator of Mongolia

Carl von Mannerheim (1867-1951)- the hero of Axis Finland during the wars with Russia, its post-war president, and a sublime military field marshal has controversially been described as being descended from Germans of the Baltic

Burkhard von Münnich (1683-1767)- major general of the Russian military in wars with the Ottomans

Ludwig von Scheubner-Richter (1884-1923)- Nazi and a significant source writer on the Armenian Genocide

Arguably, all of the Grandmasters of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the Teutonic Order can ostensibly be referred to as either Baltic or (less accurately) Prussian Germans.

Suggested Websites and Organisations

Deutsche-Baltische Gesellschaft (the German Baltic Society)- click here.

Association of the Baltic Noble Corporations- click here.

Deutschbaltischer Jugend- und Studentenring (Baltic German Youth and Student Group)- click here.

Deutschbaltische Kulturstiftung - click here.

Deutschbaltische Landsmannschaft in Bayern (Baltic German Community in Bavaria) - click here.