Displaced Communities

![]() BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

displaced by Hitler & Stalin; 95%+)

![]() GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

(over 200,000 expelled, imprisoned, displaced, emigrated; 98.5% total)

![]() VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

![]() DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

15% of German population)

![]() GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

(100-200,000 expelled after WWI)

![]() GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

(over 3,000,000 expelled

and displaced; 95% total)

![]() GERMANS OF HUNGARY

GERMANS OF HUNGARY

(over 100,000 expelled, over

300,000 displaced; 88% of total)

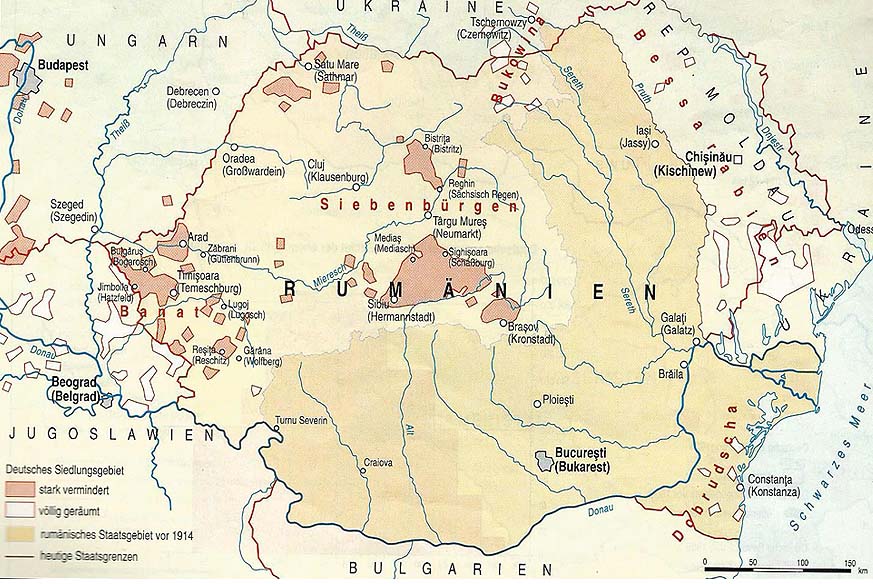

![]() GERMANS OF ROMANIA

GERMANS OF ROMANIA

(over 700,000 or 91.5% displaced by Hitler, USSR, & emigration)

![]() US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

(10,906+ interned & blacklisted) NEW!

![]() GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

(over 5,000,000 expelled and displaced, nearly 100%) COMING SOON

![]() GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

(nearly 1,000,000 to Germany and Kazakhstan) COMING SOON

Other Information

![]() OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

(documentaries, interviews, speeches)

![]() Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

(for updates, events, announcements)

![]() "Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

"Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

![]() "British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

"British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

![]() "British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

"British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

![]() From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

(memoir about wartime flight & Jewish, Polish, & German daily life near Auschwitz) NEW!

![]() Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

![]() The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

![]() Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

![]() Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

![]() Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

![]() Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

![]() Suggested Resources & Organisations

Suggested Resources & Organisations

![]() In Memoriam: Your Expellee

In Memoriam: Your Expellee

Relatives & Survivors

![]() Submit content and information

Submit content and information

![]() How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

the vanished romanian german community through

hitler's population transfer, soviet deportation, &

mass emigration

![]() Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

![]() Send

this Article to a Friend

Send

this Article to a Friend

HOW TO CITE THIS SCHOLARLY ESSAY: Institute for Research of Expelled Germans. "The disappearance of the Transylvania Saxons and Swabians from Romania through mass emigration and planned deportation." http://expelledgermans.org/transylvaniasaxons.htm (accessed D-M-Y).

The IREG flags of the Transylvania Saxons

and Banat Swabians of Romania. Both regions are equally significant

to Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian, and German heritage alike.

(Trans. shield based upon that of siebenbuerger.de, Banat

shield by Hans Diplic)

Included German minourity groups in this region: Transylvania Saxons, Transylvania Landler, Danube Swabians, Dobruja Germans, Bukovina Germans, Sathmar Germans

Total

population change resulting from expulsion, displacement,

emigration: 782,246 to under 66,646 today (91.5% lost).

_______________________________________

![]() History of Settlement, Culture

History of Settlement, Culture

![]() Population

Transfer, Planned Deportation, and Mass Emigration

Population

Transfer, Planned Deportation, and Mass Emigration

![]() Sources/Bibliography

Sources/Bibliography

![]() Population

Statistics

Population

Statistics

![]() Famous Persons

Famous Persons

![]() Suggested

Websites and Organisations

Suggested

Websites and Organisations

_______________________________________

History of Settlement, Culture, and Adaptation of Nationality

The history of ethnic German settlement in what is now Romania occurred in several phases and resulted in the formation of numerous German-speaking communities with distinct dialects and local traditions. The complicated changes in geopolitical control over northern and western Romania between various powers faciliated the diversity of the German minourities.

The first period of German colonisation was that of the Transylvania Saxons from the late 11th century to the end of the 13th, when much of modern Romania was ruled by the sceptre of the Kingdom of Hungary. The vast mountainous and forested frontier lands of Transylvania (today straddling Romania and Hungary) operated as a buffer against the incursions of Turkic tribes who were at perpetual war with the Hungarians. With this antagonism in mind, the Hungarian sovereign Géza II (1130-1162) invited farmers, artisans, knights, Catholic missionaries, and entrepreneurs from the Kingdom of Germany to settle in Transylvania. Enjoying government subsidy and protection on their journeys, the colonists were granted significant political, linguistic, and cultural autonomy. Their only overt responsibilities to the Hungarian crown were to defend Hungary from raiding Cumans and other invaders, to provide annual tribute from their community to the treasury along with 500 soldiers for the king's internal conflicts and 100 for wars abroad. The initial settlement was very small, consisting of as few as 520 families that gradually expanded into significant minourity colonies centred around Hermannstadt (Gündisch 1). Their markets were not subject to extra tariffs by the state, and their land was given marked tax incentives. The topographic remoteness of rugged Transylvania allowed other small German communities to develop their own local identities outside of the Transylvania Saxon political culture.

The German immigrants in this phase originated all over the German Empire, including Baden, the Low Countries, the Rheinland, Württemburg, Franken (Franconia), Schwaben (Swabia), and Bavaria. They retained their local regional traditions spoke a variety of German dialects, especially Low German, Alemannish, Franconian, and Swabian. Despite this diversity, all of them were called Transylvania Saxons (Siebenbürger Sachsen) upon arrival by the Hungarians, as Hungarians called most Germans Saxons ('Szász'). Upon settlement, most regional differences were subsumed as the immigrants coalesced into a developed Transylvania Saxon community in Hermannstadt. The Germans called their new homeland for the next 800 years 'Siebenbürgen' (Seven Fortresses) after the seven major urban centres that the Germans built, laying the economic and political foundations for Transylvania ever since. The Transylvania Saxons gradually forged an independent culture, society, uniform dialect ('Saksesch'), and a stratified political order of aristocratic land owners, bishops, nobles, and laymen.

The vast majourity of Saxons were farmers, with many others actively engaged in mining, forestry, artisanry, military service, monastic priesthood, and merchant commerce. The main political and economic centres were Kronstadt (today Braşov), Hermannstadt (today Sibiu), Arad, Sathmar (Satu Mare), and many others. The Saxons retained prolonged cultural, political, and merchant contact with Germany (including Austria) (Livezeanu 2000, 137). This was evident by the fact that the German Teutonic Order, ceremonially subservient to the German emperor, was given protected lands in Transylvania in the beginning of the 13th century due to their ethnocultural and linguistic affinity with the Saxons. The crusaders adorned the Saxon city of Kronstadt with powerful defences, as well as bolstered military, political, and religious foundations that made Transylvania a considerable commercial centre of the region.

The German minourity remained disproportionately powerful in comparison with the far larger Romanian and Hungarian peasant populations in Transylvania. This is evident in the fact that most of the ancient cities in Transylvania today have a blatant Germanic architectural and cultural appearance. Although there was inevitably economic interaction between the Saxon minourity and the Hungarian and Romanian majorities, the dominance of the Saxon communities created increasing tension between ethnic groups, especially between Saxons and Jews (Molnar 2001, 182). German, not Magyar (Hungarian), was the lingua franca for commerce and politics in Hungarian Transylvania despite the far larger Romanian and Hungarian populations. Nonetheless, the disparate and sparse population of family landholdings in Transylvania made inter-ethnic violence (at least in this period) almost nonexistent. Ostensibly, all three of the main ethnic groups in Transylvania (Saxons, Romanians/Vlachs, and Hungarians/Szekels) enjoyed superficial autonomy referred to as the 'Three-Nation Status'. However, the German minourity, in vast control of the region's land and commercial centres, greatly undermined the extent of this supposed autonomy.

Gradually throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Romanian principalities (Wallachia, Moldova, and Transylvania) slowly developed into significant economies and trading hubs in Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the northwestern Ottoman realm. The Romanian financial centres became a crossroads for businessmen from Germanic-ruled parts of Europe, for Bulgarians, Jews, Russians, Serbs, and Turks. Vlad Tepes Dracul (the historical figure of Bram Stoker's Dracula) accelerated this growth with his liquidation of the begger class and part of the local Roma (Gypsy) population, since foreign merchants no longer had to pay for security and therefore found Bucharest an ideal economic destination. Germans, as in much of Europe, played a significant part in Romanian economic life and growth. The main commercial street, Lipscan Street (Strada Lipscani) was and still is named after the ethnic Germans from Romania proper and from Germany coming out of Leipzig (Lipscan in Romanian). As our research in Bucharest revealed, elements of German cultural and architectural influence, as well as a blatant ethnic German minourity legacy in Romanian history are still present both visually and in Romanian historical memory.

Transylvania Saxons settle under Hungarian king Geza II (source:

siebenbuergersachsen.de)

The German minourity in Transylvania cultivated thriving commercial

centres (source: sibiu.ro)

An old Transylvania Landler church (source: landler.com)

Our photo of a portrait of Vlad Tepes Dracul in his former

palace in Bucharest, Romania. During his lifetime, Romanian

principalities developed important Balkan economies, centred

around his capital of Bucharest. Germans were a significant

factor in this economic growth and in the active merchantile

life of the bustling capital (CLICK TO ENLARGE)

Romania's Germans within the Habsburg Empire, and the settlement of the Swabians

After 1526, the political situation in the region changed dramatically. After the fall of Hungary to the Ottoman jihad in 1526, most of Hungary and its dependencies of Croatia, Slovakia, and Bohemia were annexed by the German Habsburg Empire of Austria. Transylvania was seized from Hungary and incorporated into the Ottoman Empire as a highly independent tributary. The Saxons, previously in inordinate control of Transylvania, now found their previous political power partly subsumed under the authority of mostly ethnic Hungarian statesmen. The Three Nation Status was strengthened and expanded; Hungarians, Romanians, and Saxons enjoyed significant cultural and social independence. This increasing competition would intensify ever since as a source of enduring ethnic conflict.

The devastation caused by the Muslim invasion resulted in large-scale fleeing, death, starvation, and displacement due to the despolitation of the agricultural lands of the region. Tens of thousands of Romanians and Hungarians fled Ottoman-occupied Romania and Hungary to the autonomous and remote forested lands of Transylvania. In turn, thousands of Hungarians and Germans fled Hungary westward to the safety of the Christian Habsburg Empire in Austria and northern Hungary. As a result, the Romanian population in Transylvania increased steadily, whilst the Saxon and Hungarian constituents declined (Kann 1979, 205). This further offset the longstanding Saxon hegemony over Transylvania's political foundations. Over 6,000 Saxon homes and farmlands were recorded as being abandoned and resettled by relocated Romanians as part of this demographic shift (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung).

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, Protestantism proliferated throughout Transylvania thanks to the work of German missionaries and the wide circulation of Lutheran polemics through highly developed intellectual circles and printing presses. The overwhelming majourity of Saxons adopted Lutheranism. As a result, the political and academic institutions in Saxon cities went from being dominated by Catholic priests and sees to independent Lutheran congregations and political hierarchies. A radiant Lutheran Saxon culture emerged that spawned Flemish-style artists like Tobias Stranovius and theologians like Johannes Honter. Under Ottoman autonomy, the nascent intellectual institutions of Transylvania Saxons gradually formalised into a more developed network of pedagogues, Lutheran ministers, intellectuals, city officials, and councilmen known as 'Sächsische-Universität', or 'Universitas Saxonum'. From printing presses, Lutheran schools, colleges, politicians, and intelligentsia circles, the German community in Romania forged an ordered legal corpus and political system that gradually integrated the Romanian and Hungarian majourities.

The situation in Transylvania and Romania changed again from the 17th to the 18th centuries as the Habsburgs expanded conquer all of Transylvania, Croatia, and Hungary from the obsolescent Ottoman realm. Much of the whole area, including the cities of Buda and Pest (later Budapest), was almost completely vacant due to a century of war, fleeing, and famine. In response, the German sovereigns (especially Maria Theresa and Karl VI) invited settlers from Germany to repopulate the region and found commercial and cultural centres throughout the region. These Germans, known collectively as Danube Swabians, were granted significant tax incentives and subsidy. They enjoyed the superiour political and social rights that ethnic Germans enjoyed all throughout the Habsburg Empire (Kann 1979, 460). Unlike the Lutheran Saxons, the Danube Swabian communities were strictly Catholic. Disproportionately dominant Swabian German minourities appeared in Habsburg Croatia, the Sudetenland, the Carpathians, Hungary, Transylvania, and northwestern Romania. In the lands of what is today Romania, several Swabian communities took root, including the Sathmar Swabians in Satu Mare (far west Transylvania) and the Banat Swabians (Banaterschwaben) in the Banat region that today straddles Serbia, Hungary, and Romania. At the same time, in the 18th century, hundreds of Protestants were expelled from Austria to Transylvania by Maria Theresa since Catholicism was compulsory and Transylvania was predominately Protestant. These expelled Protestant Germans developed an independent community in Romania known as the Landler Germans ('Landls').

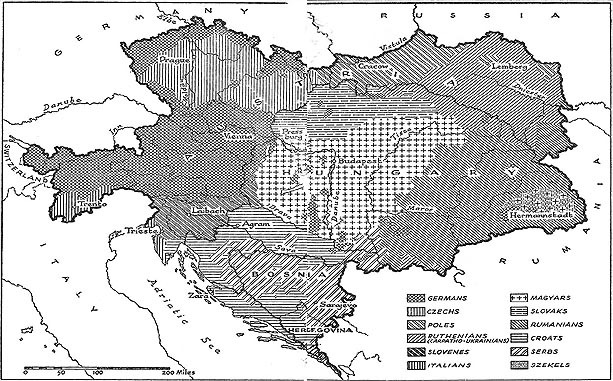

An ethnic map of the Habsburg Empire. Pay attention to the

pockets of ethnic Germans in far eastern Hungary (Transylvania).

(scanned from Kann 1979).

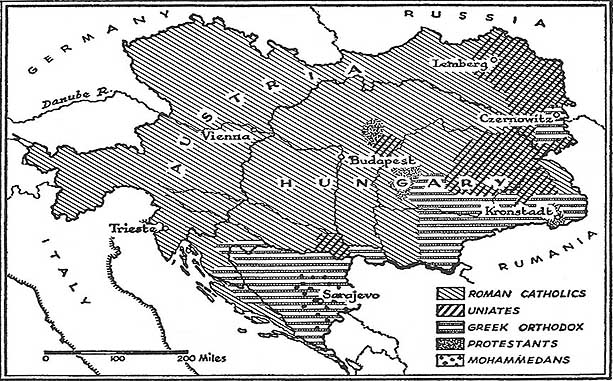

A religious map of the Habsburg Empire. Notice the significant

pockets of Uniate, Protestant, and Orthodox communities in

Transylvania. This denotes the Hungarian, German, and Romanian

communities in Hungarian Transylvania (scanned from Kann

1979)

The Habsburg system greatly altered the ethnic autonomy of the Three-Nation Status in Transylvania. The region's independence was largely abolished, and Transylvania was administered directly via a Habsburg governor (Molnar 2001, 141). The Saxons were blatantly elevated as the dominant minourity over the Hungarian and Romanian majorities. Samuel von Brukenthal, a Saxon himself from just outside Hermannstadt, was appointed Habsburg governor of Transylvania altogether. The elevated power of the Saxon minourity in Transylvania was a source of much enduring social tension. Von Brukenthal emphasised the special interests of Romania's Germans and encouraged the German Empress Maria Theresa to maintain their unequal dominance. This is evidenced by his famous letter to the Empress, in which he opposed the creation of an equalised and mixed Transylvania, 'since they were called from their homeland, the German provinces never intermixed...Instead of being a lone individual [the German] would become a mixture of many and without the virtue of the people of which he descended; he would carry the flaws and infirmities of all with whom he would mix' (Gündisch 1). However, the Habsburgs encouraged the settlement of Romanians from the Ottoman Empire in order to offset the vociferous franchise conflict in Transylvania and undermine the German-Hungarian rivalry. Romanians were not given equal rights with the other 'three nations', leading to enduring inter-ethnic disputes in Transylvania (Kann 1979, 205). Religion became the greatest divider: Calvinists and Catholics bitterly feuded with Lutherans because Lutheranism was synonymous with Saxon dominance. Both eschewed Orthodoxy as a vehicle for Romanian nationalism (Molnar 2001, 109). The ethnic franchise competition became so intense that Emperor Leopold II unsuccessfully considered abolishing the more than 300-year-old social system in Transylvania completely.

Other new ethnic German settler communities appeared in what is now Romania in the 19th century. For over a century, the Russian Empire had subsidised the immigration of ethnic Germans along the Black Sea and on the Russian frontier, including the Volga Germans. Due to competition and famine, small congregations of German families left Russia and traveled to the coastal lands straddling modern Romania and Bulgaria on the strip territory called Dobruja. This resettled community became known as the Dobruja Germans (Dobrudschadeutsche). Here, these predominately Protestant farming families formed a small minourity in southern Romania until their complete removal in 1940 (see below). As of 1930, there were 12,581 Germans in Romanian Dobruja (Wien 2004, 60). Another influential and wealthy ethnic German community emerged in the border lands straddling modern Ukraine, Romania, and Poland called Bukovina ('Buchenland' in German). From the early 18th century until the 20th, the Habsburg Empire subsidised the settlement of ethnic Germans in the region, whence they were named Bukovina Germans (Buchenlandsdeutsche). This region was populated mostly by Romanians, with large minourities of Ukrainians (Ruthenians), Poles, Germans, and Jews. Due to imperial sponsourship, the German language and the ethnic German population enjoyed tremendously inequitable influence in economics, academia, and politics. Franz-Josef-Universität in the Bukovinian capital of Czernowitz was almost exclusively conducted in German. Germans and Jews were incredibly dominant in Bukovina to the detriment of the Romanian majourity, although this inequality was gradually assuaged by 1918. In 1850, there were 150,000 ethnic Germans in Bukovina-Galicia out of 4,500,000 (Kann 1979, 404). Germans were 9.3% of Bukovina proper (Livezeanu 2000, 49). The final German community that would later become part of Romania were the Bessarabian Germans, who settled in the territory of Bessarabia that straddles modern Moldova and Ukraine. Like other German communities in Russia, the Bessarabian Germans had settled in the 19th century after Bessarabia was conquered from the Ottomans in the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-12. Primarily Lutheran, Reformed, and Pietist, the Bessarabian Germans were a heavily agricultural minourity under 100,000 with protected religious, linguistic, and local rights. After the Crimean War of 1856, most of Bessarabia and its Germans were forfeited to what would later become Romania. The Bessarabian Germans remained part of Romania until 1940, when the USSR occupied it along with the Baltic.

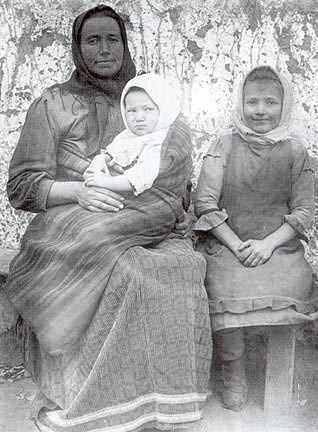

A Dobruja German settler family in Romania (source: library.ndsu.edu)

Dobruja German pioneers build disparate settlements along

the border of Bulgaria and Romania (source: library.ndsu.edu)

The relationship between ethnic groups in Transylvania changed again after Transylvania was formally incorporated into Habsburg Hungary in 1867 following the formation of the dual monarchy between Budapest and Vienna for equal ethnic rights with the Germans. When Hungarian nationalists attempted to raise the Hungarian minourity (Magyars) to power over the smaller Saxon minourity, Romanians and Saxons responded with intensive revolt (Glenny 1999, 33). The Banat region of western Transylvania became a battleground after the Hungarian Revolution, as the region's many races initiated bloody massacres and nationalist revolts, including the Banat Swabian Germans (Ibid., 51). A strong programme of Magyarisation began that sought to erode the influence of non-Hungarian minourities. The autonomy and Three-Nation Status of Transylvania was finally abolished. All extra rights of the Germans were dissolved, and Hungarians received greater ethnic and political rights than unassimilated Germans and Romanians. 1 Magyar vote equaled 12 Romanian votes in local elections (Kann 1979, 355-6). Assimilation, which rarely occurred among the Transylvania Saxons but largely did among Danube Swabians in Hungary, was a potential way out of this discriminatory ethnic policy. The Saxon response was ubiquitous. A number of Saxon academic and cultural groups appeared, such as the Society of Transylvanian History and several political parties. Others, like Adolf Schullerus, sought to protect the Saxon identity by writing Transylvania Saxon grammars and dictionaries. Most were bitterly opposed to Hungarian rule. Others, like the Saxon Lutheran pastor Stephan Ludwig Roth worked with all three ethnic groups in Transylvania seeking an equal union. Even he was eventually executed by Hungarian nationalists, accused of perfidy against Hungary. The general Saxon opposition to Hungarian rule caused the German minourity in Transylvania to look elsewhere. Most Saxons looked abroad to their common ancestral homeland in Germany during the German Revolution of 1848 that sought the reunification of Germany. One salient Saxon writing to German nationalists in Frankfurt argued, 'the world is filled with German children. We too are descendants of these roots. Geographically separated on the surface without visible bonds to the motherland, still, we live...through memories of the past and the hopes of the future with and through Germany...We are strong if Germany is strong...We want to be and remain what we have always been, an honest German people and also honest and loyal citizens of the country we belong to [Habsburg Hungary]' (Gündisch 1). Saxons and Swabians in Transylvania derided the Hungarian nationalists in parliament by describing the Magyarisation campaign as ethnic discrimination. Hungarians retorted by accusing the Saxon minourity in Transylvania of denying the rights of Romanians and Hungarian majorities for centuries (Case 2009, 36). This intensifying inter-ethnic competition for franchise in an era of explosive nationalism would continue until World War II.

In the 'Old Kingdom' of Romania (Wallachia, Moldova, and Romania proper) after independence from the Turks and unification in 1878, ethnic Germans enjoyed prosperity in a growing Romanian economy. Not only were Romania's kings who led the economic and architectural modernisation of Romania ethnic Germans from the Hohenzollern dynasty, but Germans played a significant role in trade in the Franchophile and Germanophile capital of Bucharest that soon became known as the 'Paris of the East.' Many streets in Bucharest were named after German intellectuals and sovereigns, as still remains the case today. The main merchantile hub of Bucharest, Lipscan Street (Strada Lipscani), retained its old Romanian name for the wealthy German entrepreneurs from Leipzig.

The ethnic and national situation in Transylvania changed again with the fall of the Habsburg Austria-Hungarian Empire after World War I in 1918. In the Treaty of Trianon of 1920, Hungary was shorn of 70% of its crown lands and 30% of its territory in Hungary proper. Nearly all of Transylvania was given to the young nation of Romania due to the intensive petitions of the ethnic Romanian majourity in Transylvania to finally attain political equity with the Saxons and Hungarians. At the same time, 1/5 of the Hungarians in Transylvania fled to a broken Hungary (Verdery 1985, 72). The Banat and its large German population was split between Yugoslavia and Romania after an independent Banat Republic led by the Swabian Otto Roth was crushed by Serbs in 1918. Most of the Bukovina region was given to Romania. As a result, Romania received a hugely expanded German minourity population, including Banat and Sathmar Swabians, Dobrujan, Bessarabian, and Bukovina Germans, Transylvania Saxons, and Landler Germans. The German minourity in Transylvania was largely supportive of Romania, hoping for an end to Magyarisation. Whereas Hungary had abolished the Three Nation Status and the ethnic autonomy in Transylvania, Romania promised to grant cultural and political representation to the Germans of Romania. Whereas the Hungarians had discouraged the use of German instead of Hungarian, the Romanians sponsoured Germn-language theatres, schools, representation in parliament, and political institutions. New organisations emerged like the German Party (deutsche Partei) and the German Saxon People's Council for Transylvania (Deutschsächsische Volksratt für Siebenbürgen). However, Romania, which rapidly became increasingly nationalistic, also began gradual Romanisation campaigns. Street names were changed from German to Romanian in Transylvania (like Hermannstadt to Sibiu) and bilingual education was compulsory. So too, the post-war poverty of Romania was addressed by a land reform and confiscation programme. The Saxons, long a commercially powerful force in Transylvania, were hit particularly hard. The Saxon Lutheran Church, a focal point of Saxon politics, lost 55% of its lands, and many towns lost over 50% of their private property (Gündisch 1). Of course, this policy affected Romanians as much as it did Germans.

Hitler's population transfers, the Soviets' planned deportations, and the Saxons' mass emigration

As a result of World War I's post-war territorial changes, the ancient German settler communities in Transylvania and the Banat now found themselves as part of the Romanian nation. After 1920, Romania's expansion gained more than a half-million ethnic Germans altogether, and more than 400,000 Jews (Haug 1998, 126). As of the 1930 censuses, there were 237,416 Germans in Romanian Transylvania (8.5% thereof), 275,369 in the Romanian Banat, and 31,067 in Satu Mare (western Transylvania). There were at least 32,366 in the rest of Romania proper, including Dobruja and Bukovina (Wien 2004, 60). In total, there were 745,421 Germans out of Romania's 18 million, about 4.1% (Castelan 1971, 52-53). The Banat Swabians in western Romania were the largest German minourity (Lumans 1993, 107). The Transylvania Saxons, Banat Swabians, Sathmar Swabians, Dobruja Germans, Bessarabian Germans, and Bukovina Germans enjoyed a largely peaceful and loyal membership in Romania from 1918 until 1040. They participated in political discourse in the Romanian parliament, and received cultural and linguistic recognition. Although not autonomous, the German minourities were acknowledged as a distinct and represented ethnic community within Romania. The previously separate German settler communities were now uniformly generalised on statistics and in minourity relations collectively as 'Romanian Germans' (Rumäniendeutsche).

Throughout the 1930's, Romania rapidly gravitated towards the extreme right. Rabid Antisemitism, long strong in Romanian culture, eventually merged with torrential ultranationalist movements like the Iron Guard to make Romania one of the most active participants in the independent annihilation of nearly all of Romania's large Jewish population as arguably Adolf Hitler's closest ally throughout the war. The monarchical authority of King Carol II was, by 1940, largely second to the far-reaching and charismatic dictatorship of Marshal Ion Antonescu until 1944. Hungary, too, had become an active member of the Fascist camp and a formal constituent of the Axis alongside the Third Reich and Romania under Admiral Miklós Hórthy. A very nationalistic Hungary, still greatly bitter over the loss of Transylvania, intensely asserted its irridentist claims to Romanian Transylvania. These ethnic-based territorial claims would soon bear direct consequence on the German minourities in Transylvania and Romania.

The end of the Dobrujan, Bessarabian, and Bukovina German communities through Hitler's population transfer

The Bukovina, Bessarabian, and Dobruja German communities in Romania, who had respectively settled in northern and southern Romania and contributed to the local societies for two centuries, were to almost completely disappear from Romania not as a result of post-war expulsion by the Soviets or Romanian Communists, but by the diplomatic policy of Adolf Hitler. In 1939 during the German and Soviet conquests of Poland, the Third Reich and the USSR finalised the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression and friendship. Under the treaty, the Soviet Union was given free reign to annex the Baltic states, Finland, eastern Poland, and the northeastern marches of Romania in Bessarabia (today Moldova), whilst Germany was allowed to reannex Prussia and conquer western Poland. After much dispute and diplomatic uncertainty, Bukovina was ultimately split in half, with the Soviets annexing the northern half from Romania. As a result of the pact and its subsequent diplomatic measures, significant ethnic German minourities were to fall under the rule of the Soviets, including the Baltic Germans, a significant portion of the Bukovina Germans, and the Bessarabian Germans. In addition to losing territory in Moldova and Bukovina, Romania was also to lose its Bukovinian and Bessarabian German populations as a result of Germany's diplomatic mediation. Adolf Hitler, refusing to allow these long-influential German communities from falling under the hegemony of Soviet 'Jewish Bolshevism', determined that all of these ethnic German populations were to be deported en masse and transfered to Germany under the 'Heim ins Reich' doctrine ('[come] home to the Reich'). Although Dobruja, straddling the border of eastern Romania and Bulgaria, was not incorporated into the USSR under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the tiny Dobruja German population was also to be deported to Germany because it was similarly feared that the small community would lose its ethnic characteristics and would fare better 'home' in Germany. Although Germany's decision to relocate these communities is typically considered an example of the superficiality of Hitler's pan-Germanic ideology and his complete disregard for the fate of these peoples, the political situation was far more complicated. In Hitler's mind, he was faced with the inevitable options of placing ethnic Germans under a Marxist-Leninist ideology that was deemed to be antithetical to German societies, or force them to immigrate under direct government subsidy to the exploding economy in Germany that directly catered to ethnic German interests. It was considered unavoidable.

As a result of Hitlerian diplomatic policy, the 800-year-old Baltic German community was evicted from their homes along with Romania's Bukovinian, Bessarabian, and Dobruja Germans, ending nearly 1,000 years of different phases of ethnic German pioneer settlement in Eastern Europe ('Ostsiedling'). Nearly 200,000 ethnic Germans were moved out of Romania altogether between 1939 and 1943 (Weiner 1998, 164). 13,979 Dobruja Germans were moved on German and Romanian transports from Dobruja under Germany's directive, with only 2% remaining (BMV). Nearly all of the Bessarabian German population was removed from what became the Moldavian SSR. In totality, as many as 436,000 ethnic Germans were moved out of Eastern Europe as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop treaty. Most were sent to refugee camps and subsidised housings that the German General Government in Poland had seized from Polish families (Burleigh 2001, 581). 300,000 Poles were displaced and 6,000,000 hectares of Polish land were transferred to relocated German families (Castelan 1971, 64). Interestingly, 10,000 of those deported from Romania were sent back, either for economic, political, or racial reasons (such as not being homogeneously of the German race). In the same timeframe, 150-160,000 Jews had been killed in Bukovina and Bessarabia alone by Germany, Ukrainian volunteers, and independently by Romania (Burleigh 2001, 625). Ultimately, due to economic and military shortcomings, only about 500 residences were given to the relocated Germans from the Baltic and Romania for over 250,000 people on the waiting list by the end of the war (Burlegh 2001, 596).

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact forced Axis Romania to cede its

northeastern marches, including Bessarabia and Bukovina. At

the same time, it sealed the fate of the ancient Dobruja,

Bessarabian, and Bukovina German communities of Romania that

were forcibly relocated.

The Nazification and transfer to Hungarian rule of Transylvania Saxons

The Bukovinian, Bessarabian, and Dobrujan German communities of Romania had disappeared from Romania as a result of the treaty. The Transylvania Saxons and the Swabians of the Romanian Banat, however, were not affected in the population transfer. Their closer proximity to the Reich, their developed political and social foundations, and the irredentist claims of Hungary on the Banat and Transylvania made Romania's Saxon and Swabian minourities follow a very different historical course.

Throughout their interlude of Romanian nationality, the Transylvania Saxons had formed a number of political parties and cultural organisations that interacted with Bucharest to address the local concerns of the German minourity. The Group of German People in Romania (Volksgruppe der Deutschen in Rumänien), the German People's Party, the National Saxon Party, and the German Party all joined the eclectic political movements of the Hungarian and Romanian majorities in Transylvania the 1920's and 1930's. Leftist, democratic, racialist, Christian, and far-right parties all competed. The great majourity of the Saxon parties were proud members of the Romanian nation; none directly advocated independence or incorporation into a Germany that was still very far away. Most Hungarians sought a return to Hungarian rule. Quite rapidly, the majourity of Transylvania Saxons gravitated towards the far-right, pan-Germanism, and National Socialism, inspired by the propaganda and movement of Adolf Hitler in Germany. The Volksgruppe quickly became the foremost of these social movements among Transylvania Germans, led firstly by Fritz Fabritius after 1935 before his replacement by Rudolf Brandsch. In 1933, the Volksgruppe's earlier version got 62% of the vote in the local elections in Saxon cities (Castelan 1971, 59). The Saxons' wide support for Nazi movements in Romania was used after the war by the Soviets as proof of the collective guilt of the German minourity. However, this is easily misunderstood. As in the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia, ethnic Germans tended to view Germanist National Socialism as a movement that directly addressed their local social and cultural concerns over the generalised parties of the national majorities. It does not equate to any support among the Saxons for genocide, war, or extermination of Jews or Romanians. So too, Romania itself quickly became overwhelmingly swept by extreme nationalism and Fascism, and participated on its own in the genocide of Romania's huge Jewish communities.

Volksgruppe leader Rudolf Brandsch (source: burschenschaft.de)

Although King Carol II initially tried to cripple the influence of the Saxon Nazis and the Romanian Iron Guard as a threat to his power, Axis Romania as a close ally of Nazi Germany ended up sponsouring the proliferation of Nazism among Transylvania Saxons. Whereas the Nazi Volksgruppe Party had been one of many ideological currents in Transylvania, Antonescu and a royal decree by Carol in 1940 made the Volksgruppe the sole political organ of the Germans of Romania. All other German parties and political movements in Transylvania were forcibly merged with the Volksgruppe by the Romanian government. All Saxons were officially registered as being members of the Nazi Volksgruppe. After 1939, as a result of this decree, the Transylvania Saxon community was placed under the ceremonial authority of Germany itself. The SS administrator Andreas Schmidt, under the command of Heinrich Himmler, was placed in change of Romania's German minourity. This decision made Transylvania's Germans synonymous with Nazism. This would later have great consequences for Romanian Germans when the Red Army arrived in 1944.

Much to the disgust of Romanian nationalists, the nationality of the Transylvania and its Saxons changed altogether in 1940, when under German orchestration Romania was forced to cede 4/5 of Transylvania to Axis Hungary in the 'Vienna Awards'. The transferred portion of Transylvania had more than 2,577,000 inhabitants, and 2/5 were Romanian (Lendvai 2004, 410). Whilst the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had forced Romania to lose Dobruja and Bukovina Germans, the Vienna Awards lost Romania 1/3 of its truncated German minourity, going from nearly 800,000 to less than 500,000 (Wien 2004, 64). Now under Hungarian sovereignty, the Saxons were elevated under Germany's direction to extremely autonomous status and expanded political rights. The Banat – split between Yugoslavia, Romania, and Hungary – was elevated into an autonomous province by Germany's decree when Yugoslavia was conquered in 1940. The Banat Swabian German minourity of only 20% was given authority over the whole region (Hrvatski Informativni Centar).

Tranylvania's

Saxons, like all persons of German blood throughout Europe,

were given citizenship in Germany. This decision by the German

government unknowingly would give Poland, Czechoslovakia,

Yugoslavia, and the USSR the right to expel more than 10,000,000

ethnic Germans 'back home' to the Germany that their ancestors

had not seen for centuries. In the same context as the population

transfers under the German-Soviet friendship treaty, more

than ten thousand Transylvania Saxons (now living in Hungary)

were transferred after 1940 to Germany and German-occupied

Poland (Burleigh 2001, 595). However, this repatriation

was voluntary; the vast majourity remained living in Hungarian

Transylvania. To the same end, the SS administrators in Transylvania

actively encouraged Hungarians and Germans to volunteer for

Waffen-SS legions, the German army, or the Hungarian Honvédség

with promises of job security and incentives. Artur Phleps,

a Transylvania Saxon himself and the leader of one of the

most brutal SS legions ('Prinz Eugens'), was placed in charge

of the German minourities of Transylvania and the Banat. Most

historiography argues that Transylvania Saxons were practically

'forced' to join the SS, although this is impossible to prove.

Some 75,000, or 10% of all Saxons, joined the Waffen-SS or

Wehrmacht army by the end of the war either through compulsion

or voluntarily (Wien 2004, 64). Although it is typical

to describe the Saxons as radical proponents of atrocities

who were fully deserving of any post-war retributions, it

is also worth noting that the huge Jewish minourity in Transylvania

was almost hardly disrupted at all. The Jewish population

remained relatively unchanged after the war, when the Jews

disappeared at the same rate as the Saxons themselves through

mass emigration (Haug 1998, 126). It was the Hungarians,

not the Germans in Transylvania, who began the murder of Transylvania's

Jews when the Hungarian nationalists of the Arrow Cross regime

deported them to Auschwitz in 1944, including 38,000 on trains

to Auschwitz in May alone (Glajar 1997, 526).

SS commander Artur Phleps, a Transylvania Saxon and a leader

of the Nazified German community in Romania (BBC)

By late 1944, the situation had taken a turn for the worse. King Carol II, in a last-minute attempt to save Romania from crippling post-war indemnity and Soviet reprisals, had Antonescu arrested and declared war on the Axis. The Red Army occupied Romania by late 1944, and orchestrated the seizure of power by the hitherto insignificant Romanian Communist party. With the end of World War II, due to Soviet mediation, Romania regained Transylvania and its Saxon minourity from Hungary, whilst the Banat and its Swabian Germans were split between the new Communist Yugoslavia and Romania.

Large numbers of German minourities fled Romania at the end of the war, fearing reprisals by Soviet authorities. This included war criminals guilty of horrendous atrocities as well as innocents who for ideological or economic reasons escaped the impending invasion. As many as 70,000 Banat Swabians fled the Romanian-Yugoslav border when the Red Army arrived. 40,000 were deported to the Soviet Union for forced labour, and only half returned. At least 3,000 Sathmar Swabians fled Romania as well (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). Tens of thousands of Transylvania Saxons fled the Soviet advance, given support and passports to Germany by the Volksgruppe Nazis in 1944. SS commander Artur Phleps, a Saxon himself, organised the escape of Saxons and Hungarians at the end of the war. 40,000 were planned for evacuation from Transylvania, but this only partially succeeded in time (Lumans 1993, 251). As many as 150,000 Germans left Romania in this fashion through war-time deaths, displacement, and evacuation (Die Zeit).

Whereas the Banat Swabians in Serbia were subjected to forced labour, internment, and expulsion by the Yugoslav government (see our article), the German minourity that remained in Romania (in Transylvania and the Banat) had a very different and far less brutal experience. Unlike the Czechoslovaks, Poles, Soviets, and Yugoslavs, the Hungarians and Romanians did not approve of the notion of collective ethnic responsibility, whereby everyone of German identity was automatically guilty of genocide, irredentism, and war-time atrocities. This was largely because the Hungarians and Romanians had maintained a close alliance with Nazi Germany as Fascist nations throughout the war, and Romania carried out its own Holocaust. So too, the Romanians had no cultural hatred for the Germans due to their long history of cooperation within Romania. Additionally, Romania for geographic and political reasons was not included in the Allied Potsdam Conference of 1945, in which more than 10 million Germans were ordered to be expelled to Germany. As a result of these factors, there were no expulsions or systematic persecutions performed by Romania against its German minourity.

However, the Soviets, who had lost more than 10 million citizens during the German invasion, treated the ethnic German civilians very differently when Transylvania and Romanian Moldova were occupied by the Red Army.

The forced labour and planned deportation of the Saxons by the Soviets

Soviet Order #7161, approved by Joseph Stalin in Decembre of 1944, ordered all ethnic German civilians in the occupied nations to be either expelled to Germany or deported to the Soviet Union for forced labour or imprisonment. With possible exemptions for large families dependent upon single mothers or those who were actively cited for heroic anti-Fascist resistance, all ethnic German men from 17-45 and women from 18-30 in Romania were to be shipped on trains to work in quarry mines, labour camps, and industries in the Soviet Union. The rest were to be expelled to occupied Germany. Nicolae Rădescu, the royally-appointed successor of Ion Antonescu, expressed great 'surprise' for the Soviet order and refused participation in the expulsion of Romania's German minourity. The government additionally feared that expelling a minourity of over a half-million would cripple an already-broken post-war economy. The lack of Romanian participation caused the Soviet plan for universal removal of German minourities to fail in Romania. Even West German government reports praised the clement and respectful treatment of German prisoners by Romanians (Castelan 1971, 66). This is evident in the case of Oskar Pastior, a German from Romania who was shipped for forced labour in the USSR but later returned to work in Romania's academic circles without obstruction in the 1950's. Romania's last dictator, Nicolae Ceauşescu, even later apologised for any wrongdoings inflicted upon the German minourity, although this was largely politically advantageous.

When the Red Army arrived, very appropriately, the leading Nazis and SS commanders were executed. SS officers in Transylvania and Bessarabia (Moldova) were either shot or gaoled. Tens of thousands of Romanians and Saxons were taken prisoner or executed in this fashion (Glenny 1999, 52). Thereafter, the Soviet Union proceeded to target Germans, Hungarians, and Romanians in northern Romania they considered ideologically suspicious. Like in all of Eastern Europe, the German minourities in Romania were generalised by the Soviets as collectively guilty of the atrocities committed by Germany during the war. Ultimately, under Soviet auspises, at least 75,000 German civilians were arrested in Romania, deported to the Soviet Union, gaoled, and subjected to forced labour. In most cases, deported Germans and Hungarians were held in prison and labour camps for as many as six years under famously abysmal Soviet conditions. At least 30,000 were Transylvania Saxons (Gündisch 2). As many as 10,000 (or 15%) died in Soviet custody as a result of starvation, exhaustion, and disease (Castelan 1971, 68). Most laboured in the Ukrainian SSR, especially in quarry mines. By 1951, most of the Germans who were displaced by the Soviets in Romania were released. At least half chose to, or were often forced to, escape the Soviet orbit by fleeing to occupied Germany (Clarkson). Romania lost as many as 50,000 Germans as a result of the Soviet relocation (BMV, 75E- 80E). Interestingly, the same number of Transylvania Saxons who joined the Waffen-SS (being either 'forced to' or volunteering) were shipped to the USSR for forced labour (~75,000). It is uncertain how many of the Saxons who were displaced by the Soviets were directly involved in war-time atrocities. The Soviet authorities abstractly chose the number of Romanian German SS men as the number to be subjected to deportation, but arrested indiscriminately upon any suspicion of reactionary or pro-Fascist sympathies. The vast support of Romanians for Fascism, however, was conveniently dismissed. So too, at least 8,000 Saxons died as members of the Wehrmacht or SS during the war. More than ten thousand fled before the Soviets arrived. This implies that far more were arrested and subjected to forced labour than were actually guilty of direct membership in the Waffen-SS (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). Considering that all Transylvania Saxons were automatically registered with the Nazi Volksgruppe by the Romanian government in 1940, and that many Germans had abandoned Nazism towards the end of the war, it is inevitable that many displaced Germans in Romania were not guilty of these generalised pro-Nazi associations. This is evident by the fact that liberals and Communists were targeted alongside Nazis and Fascists (Wien 2004, 65). The fact that all women between ages 18 and 30 were to be deported when women were not even allowed to join the SS proves that thousands of Germans in Romania unnecessarily suffered as a cost of Hitler's blunders and the reconstruction effort in the Soviet Union.

By 1948, through Hitler's population transfers, war-time deaths, post-war expulsions by the Soviets, and large-scale fleeing prior to the Soviet armies, Romania's pre-war German population had been almost cut in half (Wasserstein). However, it must be emphasised that the disappearance of Romania's Germans did not occur as a result of the Soviet deportations or any post-war expulsions. Germans, Hungarians, and Romanians were released from the prison camps in the USSR and generally allowed to return to Romania in 1950.

(source: dradio.de)

The disappearance of Romania's Germans through mass emigration during the Communist era

Unlike the forced displacement of the Dobrujan, Bukovinian, and Banat Germans from Romania, the main reason for the near-total disappearance of the 800-year-old Transylvania Saxon community was not expulsion, but mass emigration from the Communist People's Republic of Romania.

Communist Romania rapidly pursued a highly independent political path that was vastly divorced from Soviet influence. As a result, the German minourity was not subjected to the decrees of the Soviets that similarly caused the millions of Prussian Germans in Poland to be expelled. Romania's Saxon, However, now living in a new Communist system, Romania's Germans were now affected by the economic and political policies of Romania's dictators Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and Nicolae Ceaşescu from the 1950's until 1989. The expanding centralisation of the government in Bucharest greatly eroded the hitherto independent political and cultural institutions of the Transylvania Saxons and Banat Swabians. Under their strongly centralised regimes that are typically considered Stalinist, Romania used prison and labour camp systems that were unmatched in Eastern Europe after Stalin's death (Glenny 1999, 553). Using a secret police network called the Securitate, the economic and political policies of the Romanian Communist government had devastating consequences for the German minourities that caused them to flee in droves. Of course, Romanians and Hungarians were equally affected. However, the German community was still granted political and cultural rights that recognised them as a minourity group in Communist Romania. The Romanian Germans were represented by Rudolf Mayer under the Anti-Fascist Committee that was orchestrated by the government as a vehicle for re-educating the Germans and Hungarians towards national loyalty and Communist ideology.

Despite this multi-ethnic recognition, minourities felt noticeably marginalised by the pronounced Romanian cultural and linguistic nationalism that increasingly pervaded, especially under Ceaşescu. Romanians lionised their independent Dacian ethnic character and their marked independence from the influence of the Soviet Union. German-language schools and institutions that were previously recognised in the 1950's were merged with Romanian schools and restaffed by ethnic Romanians so that the majourity of students were Romanian even in previously German schools (McIntosh 1995, 942). This was one aspect of the Romanisation campaign that eroded on the previous independence of Romania's Germans and pressured their emigration. Again, this policy was primarily political; it was not a direct attempt to subdue the German minourity on ethnic grounds or otherwise.

Towards the end of the the Ceaşescu regime in the 1970's and 1980's, the Romanian nationalism complex expanded. Ceauşescu tapped into the Antisemitism and xenophobia that was strong in Romanian society by directly subduing the already-limited autonomy of the Hungarian, Roma (Gypsy), and German minourities (Glenny 1999, 606). All of these factors encouraged the Saxons and Hungarians, already close to the borders of Hungary, to emigrate voluntarily and leave the 800-year-old Saxon community in ruins. Admittedly, this mass exodus was never intended by the Romanian government. Its policies unintentionally ruptured the institutions and identity of the Saxon minourity. So too, due to the economic and political system of the Communist regimes, residents of distant and rural Transylvania were often relegated to move to large urban cities far away to find a job and an education. Communist Romania's centralisation and its dimunition of Transylvania's autonomy caused 600,000 persons (of all ethnic groups) to leave Transylvania to big cities, primarily Bucharest. 280,000 left Romania proper for Transylvania to work on or build collectives and new government projects (Arpad). This greatly offset the ethnic distribution of Transylvania and, when combined with the Hungarians' and Germans' mass emigration, furthered the disappearance of the German heritage of Transylvania.

The most direct policy affecting the autonomous society of the Saxons and Swabians was the policy of land and property confiscation. This dismantled the independent commercial and political foundations of the German and Hungarian communities in Transylvania by aggregating them to state control. The seizure of Saxon and Hungarian family property and farms that their ancestors had spent centuries maintaining greatly pressured a mass exodus out of Romania (Weiner 1998, 189). The Germans were accused of being disproportionately wealthy as land owners and aristocrats, and were thus a target for land confiscations and redistribution to the native Romanian majourity. The Saxons' family homes that were depopulated by the Soviets' deportations or by the confiscations were given to poor ethnic Romanian farmers (Verdery 1993, 184). Even after the collectivised lands were gradually returned in the late 1980's and especially after Ceauşescu's public execution by a mob in 1989, Saxon and Hungarian minourities in Transylvania were incensed that their concerns still went unanswered. Many argued that they only received partial shares of the returned land, whilst disproportionate percentages went to ethnic Romanians. After the fall of Communism, Germans were infuriated that much of the returned land did not go back to the original owners (the Saxon community), but to the Romanian families who had acquired the land from the Germans through the confiscations (Verdery 1993, 184). Romanians appropriately argued that the Saxon minourity had spent 800 years controlling an unequal share of Transylvania's land and subsuming the rights of the Romanian majourity. Nonetheless, these economic and political problems encouraged a mass emigration of Saxon and Hungarian families in Transylvania and caused a great deal of inter-ethnic contumacy. One Romanian responded to the Germans' complaints at their supposedly inequitable treatment by saying, 'why don't you Germans leave? What more do you want here. This land is ours' (Ibid.). It is uncertain how true or exaggerated the Saxons' complaints truly were. Again, it is grossly inflammatory to describe a system of intentional ethnic oppression by Romania against its German minourity. Inevitably, a wealthy aristocratic Saxon minourity was bound to suffer greatly from land confiscations in a Communist system. The intrusion into Romania's German communities and the seizure of their family lands was purely ideological and economic, and was not a direct discrimination against the German ethnicity in Romania.

Another decree of the Romanian Communist government under Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej inflicted great suffering upon the German Banat Swabians' community to Romania's western border with Yugoslavia. As of 1948 statistics, there were roughly 170,000 Swabians in the Romanian Banat (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). The German minourity of Yugoslavia had been treated with tremendous suspicion by the post-war Communist governments of Yugoslavia and Romania. This was because many Banat Swabians, like the Croats and Serbs themselves, had participated in horrendous ethnic atrocities throughout the war. The post-war Communist regime of Yugoslavia under Jozip Broz 'Tito' subjected most of them to forced labour and expulsion (see article). The Swabian Germans of the Romanian Banat (part of Transylvania) were not affected by collective punishment just as the Transylvania Saxons were not. However, Romania remained suspicious of the Banat Swabians for fears of disloyalty, concerns of irredentist expansion or independence, and their close proximity to a very politically discordant Yugoslavia. The Swabians were therefore subject to discriminatory status in the Romanian police state (Glajar 1997, 523). Most importantly, the Banat had a large Serb minourity that made Romania fear that the region would be incorporated into Yugoslavia. All of these factors made the minourity populations (Swabians, Serbs, Hungarians) in the Romanian Banat closely monitored by the Securitate.

Our photo of a collection of Communist-era relics in the underground

level of the Museum of the Romanian Peasant in Bucharest,

Romania. The main figure is Gheorghiu-Dej (CLICK TO

ENLARGE)

After 1951, Gheorghiu-Dej ordered the Serb, Hungarian, and Swabian populations on the Romanian-Yugoslav border to be force marched at gunpoint across hundreds of kilometres to the Bărăgan plains in southern Romania in what became known as the Bărăgan Deportations. At least 10,000 Germans, Hungarians, and Serbs were deported (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). Their family property was confiscated and annexed to the state as part of the Romanian redistribution of land from the wealthy Swabian minourity to ethnic Romanian farmers. Upon resettlement, the deportees were required to build their own homes using materials provided by the government. Some sources describe deported families living in holes dug in the ground before they completed their makeshift shacks. The Red Cross was not allowed entry to ensure the proper treatment of the deportees (De Zayas 1979, 126). Many polemical sources describe the deaths and starvation of thousands, but these are unverified and highly overstated. One source calculates as many as 125,000 dead Romanian Germans as a result of the Soviet and Romanian deportations (De Zayas 1979, 70). The West German government absurdly totaled 785,000 Germans displaced out of Romania by the Romanians and Soviets altogether, with 347,000 through expulsion and over 101,000 in death. This was oddly more than the entire population of Germans in Romania (SBD 1958). Nonetheless, the Romanian government was highly clement in this deportation. Although it did identify the Banat Germans as a dangerous ethnic group that had to be moved as a security measure, they chose to relocate them to government-subsidised housing projects rather than expel them like Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia did. Only a portion of the Banat Swabian population was displaced. The Germans of the Banat instead disappeared through voluntary emigration like the Transylvania Saxons. And in arguably Eastern Europe's most extensive police state, Romania chose not to imprison or execute a German population they considered suspicious. So too, following their relocation, new German-language schools and theatres were recognised by the Romanian government (Glajar 1997, 523).

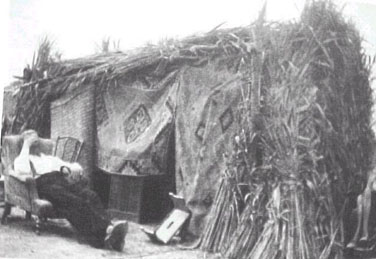

The Germans of the Bărăgan Deportations,

forced to leave their family homes and rebuild them in subsidise

housings hundreds of kilometres away (source: oestlichenachbarn.bayern.de)

(source: dvhh.org/banat/history/baragan/weber_index.htm)

(source: dvhh.org/banat/history/baragan/index.htm)

(source: dvhh.org/banat/history/baragan/index.htm)

Ultimately, regardless of the Romanian government's only moderate deportations, Romania's Germans were increasingly relegated to flee Romania. They had lost their largely independent societies and local self-government. The property that their ancestors had spent centuries developing. Pressured by the aforementioned factors, massive waves of emigration of Romania's Germans occurred from 1944 until the collapse of Communist Romania over Ceauşescu's corpse that caused the 800-year-old Saxons' and the 300-year-old Banat Swabians' communities to almost completely vanish. Ceauşescu's late 'Rational Eating Programme' that restricted the Romanian diet to detrimental rations compounded the exodus of German emigrants. This was exacerbated by a growth in anti-minourity sentiment against the Hungarians and Germans in Romania after 1989, as Romanians scrambled to define a new capitalist economy and liberal politic (Hosking 1992, 466). Tens of thousands of Gemans and Hungarians indefatiguably petitioned for exit visas to emigrate to Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Ceauşescu's regime charged an inordinately high cost for visas outside of the Communist Bloc. The impoverished majourity could not afford this, and many families were described as having their luggage packed for years in the queue (Riley 2008, 37). Many Germans and Hungarians intentionally failed at school and did as little work as possible so as to force the Romanian government to give them passports to alleviate a social drain (Verdery 1985, 74). Towards the end of the Communist era, this difficulty was gradually lifted as Romania tumbled into economic decline. Ceauşescu answered West Germany's offer to pay 7,000DM to Bucharest in return for granting exit visas to Romanian German families. Romania was anxious to grant passports to Jews in exchange for money and their departure. Romania essentially "sold" German families to West Germany for several thousand dollars each at negotiated rates per family ("Grim Romanians brighten hope...", New York Times). This was also the case in the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) by the 1980s. While this is often used as evidence of the chronic bankruptcy of socialist regimes, it must be understood that Bucharest and East Berlin were also anxious to get rid of unreliable, potentially suspicious emigrants who wanted to leave the country and essentially betray the government in the first place.

Upon being deported or approved for emigration, German families were only allowed to keep only what they could carry. Their property was forfeit to the state or Romanian farmers, or fell into delapidation before being occupied by Gypsies (Riley 2008, 38). In 1978 alone, 11,000 were allowed to leave in this fashion (Gündisch 1). The Hungarians, who have a history of centuries of antagonism with the Romanians, actively answered the opportunity. 88,000 Hungarians left Romania between 1977 and 1922,with 95% resulting from emigration under these circumstances (Haug 1998, 143). After 1980, more than 10,000 Germans left per annum. 300,000 Germans emigrated between 1950 and 1990 (Orschlies 1998, 156-73). In general, the Germans who stayed behind were the old or infirm and past the years of fertility. This exacerbated the decline of Romania's Saxon community. Romanian Germans already had a very low birthrate (Riley 2008, 43). Less than 30,000 Germans live in the Romanian Banat today, a gross decline from nearly 400,000 before 1945 (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung).

Although minourities did not suffer official discrimination on a strictly ethnic basis under Gheorghiu-Dej or Nicolae Ceauşescu, Romanian cultural and state policy became increasingly exclusive and nationalistic as Ceauşescu's cult of personality amplified. As Romania formally broke from Soviet influence and distanced itself from the Warsaw Pact (refusing to invade Czechoslovakia in 1968 despite Soviet admonitions), Romanian national identity increasingly revolved around the Vlach (or Romanian) peoples' distinct ethno-national heritage from the ancient Dacians, Thracians, and Vlad Tepes Dracul. Even Antonescu, the Fascist dictator and vicious Antisemite who allied Romania with Adolf Hitler, was rehabilitated under the Ceauşescu regime as a hero of Romanian independence. Under this increasingly nationalistic framework, the very distinct German and Hungarian minourities felt visibly disenfranchised. How legitimate these perceptions of discrimination were are a matter of dispute. However, it is universally acknowledged that Hungarian- and German-language institutions were widely closed and a policy of linguistic assimilation was accelerated. This contributed to emigration of minourities from Romania. The feeling of discrimination was evident at the end of Ceauşescu's regime in 1989. Before he was deposed by mobs and eventually executed by firing squad, Hungarian and German communities protested across the country. The most famous was that organised by the Hungarian László Tőkés in the western city of Timişoara.

The discrimination and censorship faced by minorities -- and arguably Romanians as a whole -- under the Ceauşescu regime were well reflected in the writings of Herta Müller after the 1950s, who eventually received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2009. A Banat Swabian whose father served in the Waffen-SS, Müller worked with illegal German-language study groups and resistance organisers like "Aktionsgruppe Banat" to spread dissent, to promote solidarity for the marginalised German minority that was treated with suspicion by the socialist regime, and to challenge press censorship from Bucharest. Her publications (many of which could only be published after her emigration to West Germany in the 1980s) gained significant attention across Western Europe. While denouncing dictatorship and press censorship in general, her works tend to focus on what she presented as the voicelessness of the German minority as they were displaced for forced labor in the Banat and in the Soviet Union. She especially demonised Ceauşescu's security apparatus (Securitate) and its hostility towards German and Hungarian minorities. The surviving memoirs of the Aktionsgruppe Banat and among Transylvania Saxon dissidents emphasise the atmosphere of uncertainty and the desire to escape to West Germany.

Herta Müller recounted what she saw as life under Romanian dictatorship from the perspective of the German minority (courtesy Tiki-toki.com)

The massive

depopulation of Romania's Germans through emigration led to

the collapse of the 800-year-old Saxon community. German-language

schools and academic institutions were closed due to a lack

of students. Only 96,000 Saxons were in Romania by 1990, spread

over 266 small towns and cities (Gündisch 1). Thereafter,

as many as 160,000 Germans left Romania from 1989 to 1991

(Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). Hermannstadt (Sibiu),

the ancient vibrant commercial capital of the Germans in Transylvania,

dropped from being 22% German to 1.6% today with 2,508 persons.

Kronstadt (Braşov), the old hub of the Teutonic Order knights,

went from 44% to 2.55% with 83 individuals (Centrul..).

Satu Mare, once populated by nearly ten thousand Sathmar Swabians,

is now 3.6% German. Dobruja on the border of Bulgaria, once

containing over 10,000 Dobruja Germans, now has 398 at 0.04%

(Sallanz). The

total German population in Romania dropped from nearly 800,000

(4.1%) before WWII to only 66,646 (0.3%) today (CIA

World Factbook). This is a 91.5% loss

of Romania's vanished Dobruja, Bukovina, Banat, and Transylvania

German communities.

Our photo of the main monument of public protest against the

Ceausescu regime in 1989, a commemoration of 'martyrs' near

revolution square, in Bucharest, Romania. The first stages

of revolt against the regime were, at least as is traditionally

remembered, among disenfranchised Hungarian and German minourities

(CLICK TO ENLARGE)

The auspicious status of the few Romanian Germans today

Today, the situation for the few Germans who remained in Romania is interestingly positive. Banat Swabian and Transylvania Saxon expatriat communities are represented in Germany and Austria by a number of political interest groups. Many representative circles are acknowledged by local government officials. Among them are the Community of Transylvania Saxons in Germany (website), the Community of Banat Swabians, the Centre Against Expulsions, and the Federation of Expellees. Prominent Bavarian minister Barbara Stamm publicly supported the Danube Swabian and Saxon interest groups, whilst in München the mayor Gertraud Burkert met with the Romanian and Hungarian consulates representing the displaced Swabians and Saxons. Many Romanian Germans sent into diaspora ship money back to their relatives in Romania. A small number have even returned to Romania to promote investment and construction (Riley 2008, 43-44). Some Romanian Germans – both in Germany and Romania – express a type of identity crisis. Some living in Germany fear that they are subjected to ethnic discrimination for speaking Romanian, and are derided as Gypsies or other Romanians. In Romania, others assert that they are slandered for being Germans (Ibid.). The few Germans living in Romania today are described by some scholars as being 'unbound', with their independent ethnic and cultural characteristics diminished as an act of survival and also as the key to success in once-Saxon cities that now are overwhelmingly Romanian (Verdery 1985, 66). There is still a noticeable inter-ethnic antagonism, especially between the mutually antipathetic Hungarians and Romanians.

In Romania, the German minourity is well represented in society and even in the national government by a number of social movements. The main political interest group of the entire German minourity is the Democratic Forum of Germans , or the Forumul Democrat al Germanilor din România (website). Others include the Transylvania Regional Forum, the Democratic Forum of the Banat Germans, and several academic and Lutheran congregational circles. There are also a number of German-language newspapers, including the Deutsche Zeitung für Rumänien (website). Most saliently, despite the fact that Hermannstadt (now Sibiu) as the old Transylvania Saxon capital is only 1.6% German, its Romanian population overwhelmingly voted for the Democratic Forum of Germans and elected the Saxon Klaus Iohannis as their mayor. In 2014, he was even elected president in a surprising national election that shocked many European political analysts (see below for explanation). Many prominent national directors, curators of museums, and university officials are of ethnic German descent, including Dr. Ernest Oberländer-Tarnoveanu, the chairman of the Romanian National Commission of Museums and Collections. In our interview with him, he demonstrated that German minourities effectively adapted their lifestyle and national identity to the changing political and economic conditions in Romanian history under Communism and the democratic period after 1989. Many solely speak Romanian in the home, but retain their German ethnic and cultural distinctions. Others maintain a combined German-Romanian identity, defining themselves as being ethnically and culturally German but nationally loyal to the state of Romania.

Romania has formally acknowledged the deportations (performed by Romania) and expulsions (done by Soviets) against the Germans. Even the official website of the city of Sibiu commemorates the disappearance of the Saxon minourity. Many signs in the city are ceremonially in German despite the disappeared German population. Many historiographic sources and scholars readily engage the plight of Romanians and Germans alike throughout the 20th century.

The 800-year story of Romania's Germans is unique of the many post-war displacements of German minourities in Eastern Europe. The Dobruja, Bessarabian, and Bukovina German communities disappeared as a result of Adolf Hitler's foreign policy. But whereas Czechoslovakia directly expelled more than 3,000,000 Sudeten Germans and Poland and the USSR expelled over 5,000,000 Prussian Germans, 91.5% of the Romanian German community of almost a million disappeared voluntarily, pressured to flee by the disastrous policies of the Romanian Communist governments that eroded the independent political and economic foundations of minority settler communities.

However, a nearly unprecedented landmark event occurred in 2014 that surprised many Romanians, Transylvania Saxons, Transylvania Hungarians, and political scientists alike. In the presidential election following the departure of President Traian Băsescu, Klaus Iohannis, the Transylvania Saxon mayor of Sibiu (Hermannstadt) was elected president in a surprise defeat of former prime minister Victor Ponta. As mentioned above, the German minority (less than 2% of the population) has often enjoyed disproportionate success thanks to ongoing problems in Romania's corrupt political economy. In explaining how a minority might be elected to such a high office in a society that is often reputed for xenophobia and Anti-ziganism, many analysts argue that Romanians are looking for a fresh start with a new political faction that might be less prone to nepotism, corruption, and fraud. Some voters hope that electing a fresh official from a region reputed for its comparatively healthy local economy might send a message and undermine the corruption that has characterized the status quo (Kulish, 2009). Other voters hope that electing Iohannis might help further integrate Romania with the European Union by encouraging investment from its largest economy: Germany. Iohannis himself has helped stimulate investment from Siemens, Renault, and other Western European corporations (Kulish, 2009). Despite this, the traumatic legacies of history remain. In many rallies, television interviews, and comments on blogs and websites, many state that Romania will never fully accept Iohannis or the Transylvania Saxons as their own because they are "not real Romanian[s]," all while living there for almost eight centuries (al-Jazeera, "Voting ends in Romania's presidential election" ).

The evolution of the German minority in Romania until today (CLICK TO ENLARGE) (source: Heinen, Situation in der Gemeinschaft unabhaengiger Staaten).

Klaus Iohannas of the Transylvania Saxon minority, elected President 2014 (courtesy catavencii.ro)

Transylvania Saxon interest groups are

active in Romania, Germany, and Austria (source: siebenbuergen.de)

Personal interviews and research in Romania with descendants of Saxons adopting to a Romanian-German identity in modern Romania.

Heinen, Ute. "Die Situation in der Gemeinshaft unabhaengiger Staaten (GUS)." Informationen zur politischen Bildung, 267, 2. Quartal 2000.

Our interview with Dr. Ernest Oberländer-Tarnoveanu, Chair, National Commission of Museums and Collections.

Arpad, Varga. "Hungarians in Transylvania between 1870 and 1995." Magyar Kisebbség 3-4, 1998: 331-407.

Bundesministerium für Vertriebenenfrage. ""Umsiedlung der Volksdeutschen aus der Dobrudscha im Jahre 1940." Constanţa, 1957.

Burleigh, Michael. The Third Reich: A New History. Hill and Wang, 2001.

Case, Holly. Between States: The Transylvanian Question and the European Idea during World War II. Chicago, IL: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Castellan, Georges. "The Germans of Rumania." Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 6, No. 1, Nationalism and Separatism (1971): 52-75.

Centrul de Resurse Pentru Diversitate Etnoculturala "Structura Etno-demografică a României." http://www.edrc.ro/recensamant.jsp.

CIA World Factbook

Clarkson, Sue. "History of the German Settlements in Southern Hungary." http://www.feefhs.org/links/banat/bhistory.html.

De Zayas, Alfred. Nemesis at Potsdam: the Anglo-Americans and the Expulsion of the Germans: Background, Execution, Consequences. London: Taylor & Francis, 1979.

Die Zeit. "Rumänische Tragödie." 16 Septembre, 1954, Nr. 37.

Glajar, Valentina. "Banat-Swabian, Romanian, and German: Conflicting Identities in Herta Müller's 'Herztier'." Monatshefte, Vol. 89, No. 4 (Winter, 1997): 521-540.

Glenny, Misha. The Balkans. New York: Penguin Group, 1999.

Gündisch, Konrad. "The History of Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons." http://www.sibiweb.de/geschi/7b-history.htm.

Gündisch, Konrad (2). "Wahrung der Eigenständigkeit trotz wechselnder Staatszugehörigkeit: Eine 850-jährige Geschichte im Überblick." http://www.siebenbuerger-bw.de/buch/sachsen/7.htm.

Haug, Werner and Courbage, Youssef. The Demographic Characteristics of National minourities in Certain European States. Council of Europe, 1998.

Hosking, Geoffrey. The First Socialist Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Hrvatski

Informativni Centar. "Medjunarodni znanstveni skup