Displaced Communities

![]() BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

BALTIC GERMANS (150,000

displaced by Hitler & Stalin; 95%+)

![]() GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

GERMANS OF YUGOSLAVIA

(over 200,000 expelled, imprisoned, displaced, emigrated; 98.5% total)

![]() VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

VOLGA GERMANS (over 400,000 expelled by Soviets to Kazakhstan)

![]() DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

DUTCH GERMANS (3,691 expelled,

15% of German population)

![]() GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

GERMANS OF ALSACE-LORRAINE

(100-200,000 expelled after WWI)

![]() GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

GERMANS OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA

(over 3,000,000 expelled

and displaced; 95% total)

![]() GERMANS OF HUNGARY

GERMANS OF HUNGARY

(over 100,000 expelled, over

300,000 displaced; 88% of total)

![]() GERMANS OF ROMANIA

GERMANS OF ROMANIA

(over 700,000 or 91.5% displaced by Hitler, USSR, & emigration)

![]() US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

US Internment of German-Americans, Japanese, & Italians

(10,906+ interned & blacklisted) NEW!

![]() GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

GERMANS OF POLAND, PRUSSIA

(over 5,000,000 expelled and displaced, nearly 100%) COMING SOON

![]() GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

GERMANS OF RUSSIA/UKRAINE

(nearly 1,000,000 to Germany and Kazakhstan) COMING SOON

Other Information

![]() OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL NEW!

(documentaries, interviews, speeches)

![]() Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

Follow us on FACEBOOK NEW!

(for updates, events, announcements)

![]() "Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

"Reactions of the British Public and Press to the Expulsions" NEW!

![]() "British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

"British Humanitarian Responses - or lack thereof - to German Refugees" NEW!

![]() "British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

"British Political Responses to the German Refugee Crisis during Occupation" NEW!

![]() From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

From Poland, to Czechoslovakia, to Occupied Germany: My Flight from the Red Army to the West

(memoir about wartime flight & Jewish, Polish, & German daily life near Auschwitz) NEW!

![]() Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

Daily Diary of Forced Labor in the Mines of Soviet Ukraine NEW!

![]() The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

The problem of classifying German expellees as a 'genocide'

![]() Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

Why the German, Czech, and Polish governments reject expellee commemoration

![]() Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

Distorted historical memory and ethnic nationalism as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

Ethnic bias and nationalist revisionism among scholars as a cause for forgetting expellees

![]() The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

The History and Failure of Expellee Politics and Commemoration NEW!

![]() Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

Expellee scholarship on the occupations of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland, 1918-1945

![]() Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

Sexual Violence and Gender in Expellee Scholarship and Narratives

![]() Suggested Resources & Organisations

Suggested Resources & Organisations

![]() In Memoriam: Your Expellee

In Memoriam: Your Expellee

Relatives & Survivors

![]() Submit content and information

Submit content and information

![]() How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

How to support German expellees / expellee political lobbies

the forced labour, imprisonment, expulsion, and emigration of the Germans of Yugoslavia

![]() Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

Print this Article •

Font

Size: -

+ •

![]() Send

this Article to a Friend

Send

this Article to a Friend

HOW TO CITE THIS SCHOLARLY ESSAY: Institute for Research of Expelled Germans. "The forced labour, imprisonment, expulsion, and emigration of the Germans of Yugoslavia." http://expelledgermans.org/danubegermans.htm (accessed D-M-Y).

The IREG flags of the Banat and Vojvodina

Swabians of Serbia, Croatia, Romania, and Hungary (shield

symbolising Ottoman mosques by Hans Diplic)

Included German minourity groups in this region: Banat Swabians, Danube Swabians, Vojvodina Germans, Gotscheers

Total

population change resulting from expulsion and displacement:

from nearly 500,000 to ~7,302, 98.5% loss

_______________________________________

![]() History of Settlement, Culture, and Adaptation

of Nationality

History of Settlement, Culture, and Adaptation

of Nationality

![]() The

Nazi period, and the Yugoslav confiscations, forced labour,

imprisonment, and emigration of Germans

The

Nazi period, and the Yugoslav confiscations, forced labour,

imprisonment, and emigration of Germans

![]() Sources/Bibliography

Sources/Bibliography

![]() Population

Statistics

Population

Statistics

![]() Famous Persons

Famous Persons

![]() Suggested

Websites and Organisations

Suggested

Websites and Organisations

_______________________________________

History of Settlement and Culture, and Adaptation of Nationality

Ethnic German pioneer settlement in the Balkans and Central Europe occurred gradually over many centuries since the 11th century, and in response to numerous political and historical stimuli. Small populations of German farmers were first invited into Serbia, eastern Bosnia, and Hungary by the Hungarian sovereign Géza II in the 12th century and the Serbian Tsar Dušan the Mighty in the 14th century (Singleton 1985, 41). However, full-scale German immigration into Hungary and the lands that formerly comprised Yugoslavia – especially Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, and Bosnia – began comparatively late, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

At this time, most of the entire region was dominated by the German Habsburg Empire centred around modern Austria. After the defeat of Hungarian king Lajós at the Battle of Mohács by the invading Ottoman Muslim legions in 1526, the Habsburgs incorporated the lands of the Hungarian Crown that were yet unconquered by the Muslims, including the northern portions of Hungary and its subordinate territories of Croatia-Slavonia and Bohemia. By the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718, the once-respledent Ottoman Empire was crushed by the Habsburgs and sent tumbling towards its gradual collapse. The Habsburgs rapidly grew to incorporate all of Hungary, Croatia, Transylvania (today northwest Romania), and the northern portions of Ottoman Serbia called the Vojvodina and Banat that today straddle Hungary, Romania, and Serbia. Bosnia and Serbia remained under Ottoman hegemony until 1878, and Serbia proper was never absorbed into the Habsburg orbit. What is now Slovenia had long been under Habsburg authority. It was under this geopolitical context that the German Habsburg monarchy, in overwhemingly disproportionate ethnic control of this massive empire, subsidised ethnic German settlement throughout its dominion and into the lands of what would later become Yugoslavia.

There were many provocations for Habsburg government sponsourship for ethnic German immigration. Hungary and the frontier steppe lands had been decimated and incinerated during the wars against Muslim invasion, leaving previous economic and agricultural centres in ruin. Buda and Pest (later Budapest) were almost completely depopulated, and huge Christian Serb and Hungarian populations had fled northward from the Ottoman janissaries. This left huge swathes of the newly-expanded Habsburg orbit ripe for resettlement as a means of generating agricultural and material output. Equally salient was the irascible ethnic situation in the highly diverse Habsburg Empire, which included an unequally powerful German elite and Hungarian, Serb, Romanian, Croat, Slovene, Czech, and Slovak subjects with diminished linguistic, cultural, and political rights. The Hungarians, who constituted the second most powerful ethnic group in the empire's nascent developing dual monarchy system, bitterly struggled to gain equal franchise with the ethnic Germans. In its efforts to subsume the influence of the rival Hungarian nobility, the Germans encouraged the settlement of non-Hungarian minourities in the Hungarian half of the empire. The immigration of Slovaks and other Slavic peoples was also encouraged alongside Germans to offset Hungarian influence. Sponsouring the immigration of ethnic German communities into the empire and what would later become Yugoslavia therefore ultimately strengthened the interests and monopoly of the German economic and political elite. Lastly, the Habsburgs encouraged immigration into the northern portions of modern Yugoslavia (especially the Banat and Serbian Vojvodina) as a means of militia defence against feared Ottoman aggression in the southerly fortifications known as the Military Frontier (Militärgrenze).

Under

these circumstances, the Habsburg sovereigns (especially Leopold

II and Maria Theresa) formalised the Colonial Commission after

1766, encouraging and subsidising the immigration of German

farmers and entrepreneurs from the predominately Catholic

states of southern Germany. This sponsourship remained to

a declining degree until the fall of the empire in 1918. Most

of these German immigrants originated in the regions of Baden,

Schwaben (Swabia), Würrtemburg, Bavaria, Hessen, Luxemburg,

and Elsaß (Alsace) in France.

They retained a variety of local Germanic traditions, a strong

Catholic faith as was largely compulsory during this timeframe

in the Habsburg Empire, and spoke a number of local German

dialects including Swabian (Schwäbisch), Franconian (Fränkisch),

and Alemannisch. Despite these minute local distinctions,

the German immigrants into the lands of the Habsburg Hungarian

Crown and what became Yugoslavia were collectively called

Danube Swabians (Donauschwaben), since most

settled along the Danube river. The Danube Swabians who settled

in the Banat and Vojvodina regions straddling Serbia, Romania,

and Hungary became known as Banat Swabians.

The main loci of German pioneer settlement in the later Yugoslavia

were in today's Serbia and Croatia. Significant German-populated

towns and cities, today almost completely bereft of Germans

following the displacement of 98.5% of Yugoslavia's Germans,

included Apatin, Hodschag (today Odžaci), Knićanin (Rudolfsgnad),

Novi Sad (Neusatz) in the Vojvodina, Katschfeld (Jagodnjak),

Gakovo, Kruschiwl (Kruševlje), Vukovar, and Esseg (Osijek).

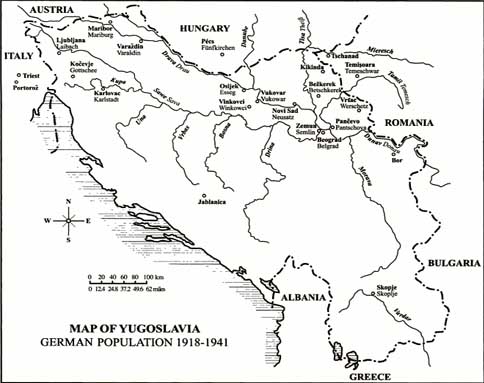

A partial map of German towns developed during Habsburg immigration

sponsourship. CLICK TO ENLARGE. (Scanned

from the book Casualty of War: A Childhood Remembered,

by Luisa Lang Owen)

Upon settlement, the German families were given safe passage to protected agricultural lands with auspicious tax exemptions and incentives, free livestock, equipment and seeds, and housing (Kann 1979, 200). With the German immigrants enjoying exorbitant government subsidy and now a sizable minourity in the significant urban centres of Pest, Buda, Novi Sad, and Bratislava, the disproportionate ethnic rights of the Germans of Austria were extended to the new ethnic German immigrants (Kann 1979, 460). As a result, the Danube Swabians became quite wealthy and politically influential despite being a small ethnic minourity. Most German settler villages and cities developed a very Germanic architectural and cultural appearance, whilst the commercial and cultural language of towns settled by German minourities rapidly shifted from Slavic ones to German. These factors were sources of enduring inter-ethnic tension, as Slavs and Hungarians increasingly rallied for self-determination against the Germans. So too, in areas primarily populated by Orthodox Serbs or Calvinist Hungarians, the presence of Catholic priests or churches became synonymous with what was perceived as the encroaching presence of German imperialism.

In the 19th century alone, over 150,000 German immigrants arrived in the southern marches of Hungary (Prokle 2003,22). 160,000 arrived in Croatia-Slavonia alone (Lumans 1993, 117). The Vojvodina – the northern region of Serbia ruled by the Habsburgs – had over 285,920 Germans by 1880, or 24.4%(Kocsis 2), The Banat region altogether had as many as 388,000, at 24.5% (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung), and 325,000 by 1910, or 21.4% (Jelavic 1983, 316). In all of the lands of the Hungarian Crown, the total population of Germans (primarily Danube Swabian immigrants) was 1,200,000 by 1843, 1,955,250 in 1880 (12.5% of the Hungarian dominion), and 2,046,828 by 1910, or 9.8% (Kann 1979, 605-8). After the gradual Habsburg occupation of hitherto-Ottoman Bosnia in 1878, the Habsburg government extended small-scale ethnic German and Slovak immigration into Bosnia and Herzegovina, totaling over 10,000, and of those at least 2,000 Swabians in the first phase (Malcolm 1996, 143). Bosnian nationalists immediately responded to this subsidised ethnic caste with parliamentary petitions and complaints to Vienna as part of the empire's enduring ethnic friction (Ibid). Modern Slovenia, which was integrally attached to the Habsburg Empire for centuries, possessed an inordinately powerful German economic, intellectual, and political caste that was largely unaffected until the fall of the empire. There were as many as 38,631 Germans in Slovenia by 1921 (Wolff 2002, 147).

Country life and subsidised settlement of the Danube Swabians

in the lands of the Habsburg Hungarian crown (paintings from

the excellent artist Stefan Jäger at www.stefan-jaeger.net)

The largest German population in the former Yugoslavia was in the Habsburg Banat and Vojvodina, two adjacent territories that are today split between Croatia, Romania, Hungary, and especially Serbia. The drastic ethnic diversity of the region meant that it became a battleground for each group's aspirations for autonomy, irredentism, or total discord. The Danube Swabians in what would become Yugoslavia were thus often forced to adapt their nationality in response to contast political changes and especially the eventual fall of the Habsburg Empire and the establishment of independent Yugoslavia in 1918. The Serbian and Hungarian revolutions of 1848 against the German Habsburgs for bolstered political and national franchise turned the German-populated regions into a warzone of competing political maxims, rife with bloody massacres between Hungarians, Serbs, Ashkenazi Jews, and Swabians (Glenny 1999, 51). After Serbian nationalists failed to establish an independent Serbia in the Vojvodina, Vienna acquiesced in 1860 to the bitter contumacy in the region by establishing the superficially autonomous German crown land of the Voivodeship of Serbia and the Banat of Temeschwar. Its governor, a German, was directly appointed by the emperor, marking a continued legacy of struggle between the German elite and the Slavic majourity. This ephemeral shift in nationality for the Danube Swabians in the future Yugoslavia shifted again after the Hungarian nationalist triumph of 1867, which established a dual monarchy of perfunctory ethnic equality between Germans and Hungarians. The Serbs and Germans of the Vojvodina were subsequently directly obeisant to a highly nationalistic Hungary, which began a programme of intensive cultural and linguistic assimilation called Magyarisation (Kann 1979, 320). Most Swabians responded with topical assimilation by learning Hungarian and displaying Hungarian culture, whilst retaining their German identity in private. The Croats, Slovenes, and Bosnians of the Habsburg Empire were unable to organise an effective national revolt prior to the empire's expiration. As a result, the dominant position of the small Swabian minourities in these regions was often unaffected overall by nationalist ferment.

A map of the Vojvodina, where most Germans of the future Yugoslavia

settled and lived until their displacement. The Banat region

(see below) is adjacent to the east. During the Habsburg era

when Germans were invited for subsidised immigration, the

Vojvodina acted as a military buffer against the Muslim Turks

ruling Serbia proper (source: map.primorye.ru)

The Banat region is highlighted at centre. The Banat and Vojvodina

were historically exchanged between Serbia, Hungary, and Romania.

(source: birda.de)

The Danube Swabians responded to the crisis of nationalism and political franchise by petitioning their sponsours in Vienna for an autonomous Danube Swabian polity in the Banat in order to propitiate the increasing dominance of the Serbian and Hungarian nationalists. Ultimately, the interests of the Danube Swabian minourity were subdued by Hungarian national aspirations. Germans within the Hungarian orbit (Croatia, Slovakia, Hungary, and Transylvania) were subject to the Magyarisation process until the fall of the empire in 1918. Partly in response to this ethno-political conflict, over 79,500 Germans emigrated out of the Vojvodina and Banat by 1913 (Kocsis 2001, 146). Despite this loss of cultural autonomy for Germans and the cessation of direct subsidy by Vienna, Swabians in Hungary and the future Yugoslavia adaptively represented their independent interests through an array of approaches. Among these mechanisms were the formation of political parties (especially the Hungarian German People's Party), newspapers, academic circles, and political manifestos that retained a separate German ethnic identity even during compulsory assimilation. (See Expelled Germans of Hungary under Magyarisation for more analysis).

The ethnic and geopolitical situation, as well as the nationality status of the Germans of what would become Yugoslavia changed cataclysmically with the fall of the Habsburg Empire after its defeat of World War I in 1918. Seizing the long-sought opportunity for self-determination and the dismantlement of the 500-year German minourity caste, Slavic nationalists in Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Monenegro, Serbia, and the Vojvodina declared the merger of these lands into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in 1918 (later Yugoslavia). Disproportionately ruled by the Serbs and a Serbian monarchy based in Belgrade, Yugoslavia was a limited confederacy of each South Slavic minourity group. The smaller non-Slavic populations, including the Swabians and Hungarians, now found their previous dominance destroyed. German and Hungarian nationalists under the Swabian Otto Roth in the Banat and Vojvodina responded by declaring the establishment of an independent Banat Republic (Banater-Republik) in 1918. This ephemeral state was immediately crushed by the Yugoslav army, and the Vojvodina altogether was annexed into Yugoslav Serbia along with its Swabian and Hungarian minourities. Danube Swabians – long supported by Vienna's hegemony over the region – were now ethnic minourities in independent nations that no longer catered to the German or Hungarian communities. The Swabians of Yugoslavia henceforth became known as Yugoslav Germans (Jugoslawiendeutsche). According to 1921 statistics, the German minourity population of the new Yugoslavia included 513,412 total in Yugoslavia altogether (4.21%), and of that 328,173 in the Serbian Banat and Vojvodina, 122,836 in Slavonia (Croatia), and 38,631 in Slovenia (Wolff 2002, 147). Most Germans of Yugoslavia, until their displacement after World War II, lived in the northern region of the Serbian Banat and Vojvodina.

The German minourity experience under Yugoslav rule (1918-1941) was erratic. Historiographic polemics that depict a period of anti-German oppression by the Slavs, which forced them towards Nazification, are highly exaggerated. The Germans at only 4.21% were naturally afforded the diminshed political franchise and influence of any minourity in Yugoslavia. As Yugoslavia gravitated towards a highly-centralised dictatorship of the Serbian monarchy, the Belgrade government instituted a continuous programme of land and property confiscations, nationalisation, and limited redistribution. With the dissolution of the German Habsburg regime, independent Yugoslavia experienced a glaring problem of an inordinately wealthy ethnic German landowner class and a poor Slavic peasant majourity. Although the confiscations did not discriminate on racial grounds and targeted both Slav and German alike, the higher station of the Swabians meant that they were particularly affected by the government's incursions against the nobility. These factors, combined with the worsening dimunition of the cultural and personal autonomy of the Swabians under the centralising Belgrade monarchy, further pressuring Swabians to attach themselves to racialist political currents that directly addressed their independent cultural interests.

Despite these estate confiscations, the small Swabian minourity continued to exert powerful influence in early Yugoslavia prior to the establishment of a dictatorial monarchy under King Aleksandr by 1929. The Swabian Georg Weifert (1850-1937), one of Yugoslavia's most important industrialists, economists, and the president of the Serbian parliament, exemplified the fact that the German minourity was not subjected to systematic discrimination, and contributed greatly to the economic and political evolution of early Yugoslav society. Ethnic Germans remained unusually wealthy in proportion to their small population. In the Vojvodina – the breadbasket of Yugoslavia where most Germans and Hungarians resided – Germans were only 1/4 of the population (Hrvatski Informativni Centar), but dominated over 50% of the economy. 80% of products and material exported out of the region originated from businesses owned by German families (Wolff 2002, 150). As such an influential minourity in Yugoslavia's commercial centres in Vojvodina, this gave the Germans an auspicious position during the first period of Yugoslav statehood.

Georg Weifert, president of the Serbian parliament and one

of Yugoslavia's most important early industrialists and economists,

exemplifies the auspicious position the German minourity enjoyed

in early Yugoslavia (source: djordje-vajfert.org)

The autonomous cultural, linguistic, academic, and political interests of the German minourity were successfully represented via a variety of state and community mechanisms. The German Party (Partei der Deutschen), founded in 1922 with state recognition, consistently attained between 5 and 8 seats in the national Yugoslav parliament, giving them a commensurate influence on the government and its jurisprudence (Sretenovic 2002, 48). A plethora of other political and academic organs addressed German community interests, including the German Economic Party, the Kočevje Peasants' Party (Gottscher Bauerpartei), the Swabian German Cultural Union, the Kulturbund (Culture Federation), the German Association of Women, and the Association of German Medical Doctors. Ethnic German communities, especially around Novi Sad (Neusatz), Apatin, and Rudolfsgnad (Knićanin) had a total of 258 schools with both German and Serbocroatian instruction, 400 cultural and agriculture associations and unions, a separate German-language printing house, over 30 periodicals and magazines of their own, and one daily newspaper called the Deutsches Volksblatt (Ibid., 50).

As is apparent, the experience of Swabians in the early phase of Yugoslav independence was not one of oppression or subjugation. The Danube Swabians had remarkably adapted their nationality to several political transitions since their settlement in the region in the 18th century, including rule by the Habsburgs, the Serbian voivodes, the Hungarian nationalists, and finally that of the independent Yugoslavs. They operated as an integral actor in the Yugoslav economy, statecraft, industry, pedagogy, and the intelligentsia. There is no evidence of any marked inter-ethnic contumacy between the Slavic majourity and the German minourity prior to the dictatorship of the Belgrade monarchy in 1929. A variety of ideological, social, and cultural factors were necessary to eventually cause the Germans to gravitate towards racialism and National Socialism (Nazism) prior to the invasion of the Third Reich in 1941 and the eventual displacement of 98.5% of Yugoslavia's German community thereafter.

The Nazi period, and the Yugoslav confiscations, forced labour, imprisonment, and emigration of Germans

Gradually throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Danube Swabian minourity in Yugoslavia rapidly shifted towards various manifestations of pan-Germanic nationalism, Nazism, racialism, and irredentism. The political and social motivations for this digression were manifold. Apologetic historiographic sources explain the radicalisation of the Yugoslav Germans by exaggerating a systematic oppression of the German and Hungarian minourities by the Slavs. The other side, as maintained after the war by the vengeance-seeking Yugoslav Communists regime, was that the German minourity was guilty of a longstanding conspiracy of the extreme right for total independence from Yugoslavia and the subjugation of the other Slavic groups within Yugoslavia. Both interpretations are exaggerated and limited, and ignore the diverse reasons why Germans shifted towards Germanic nationalist movements.

When the hitherto ceremonial monarchy in Belgrade under King Aleksandr began asserting itself as a dictatorship over Yugoslavia in 1929, the nation's many ethnic groups now found their previous autonomous ethnic and community franchise rights significantly obstructed. Germans, Hungarians, and Slavs alike were no longer able to address their local affairs through political and legal means due to Belgrade's dominance. The German Party was banned completely, as was the nationalist Kulturbund even before it became Nazified. Although this abolition was later lifted, the social division had already been inflicted. The diminished franchise of non-Serbian minourity groups was further exacerbated by what was perceived as their increasing subservience to the Serbs and the Serbian sovereign. The imposition of Serbocroatian as the bolstered official language to the detriment of other minourity languages further inhibited the desire for non-Serbian groups to profess loyalty to the Yugoslav state. It was the transition of Yugoslavia from a system of multi-ethnic political confederation to a system of Serbian hegemony that pushed minourity groups toward radicalism and discord. The Danube Swabians, like the Croats and Hungarians, rapidly began to separate themselves from integration with Yugoslavia and joined political movements that directly addressed their greatly stymied cultural interests. Like the Sudeten Germans in Czechoslovakia, radical pro-German movements that espoused German nationalism became far more relevant to Yugoslavia's Germans than subservience to a highly alienating Serbian monarchy. It was this process, rather than any malevolent desire for genocide or racial mass murder, that caused the Germans to rapidly affiliate with Nazism. Despite the inauspicious situation of the ethnic Germans within Yugoslavia under Aleksandr I, the king strengthened Yugoslavia's warming relations with Germany and other Axis countries by formally joining the Tripartite Pact in 1941, an economic and political partnership between Fascist-leaning nations. The pact was not a military partnership; Yugoslavia remained a neutral nation whose borders were protected from Axis nations' troop movements.

King Aleksandr I of Yugoslavia, who after 1929 consolidated

the federalised nation into a monarchical dictatorship and

greatly polarised minourity groups' aspirations for self-determination

(source: royalfamily.org)

The main representative organs of Yugoslavia's Germans in the 1920's were the German Party (Partei der Deutschen) and the Schwäbisch-Deutscher Kulturbund (Swabian German Culture Federation). The Kulturbund was identified after the war by the Communists as a criminal organisation and all of its members (most of the German population) were therefore excoriated as pro-Nazi traitors. Although the Kulturbund eventually became a vehicle for National Socialism (Nazism) that enjoyed the support of most Yugoslav Germans and the Third Reich, it initially began as a moderate, integrated German cultural association. Founded in 1920 by Johann Keks, Stefan Kraft, Peter Heinrich, and Georg Grassel, the movement did not call for a discord from Yugoslavia, a union with Germany, or advocate any violence. Using the mantra "Staatstreu und Volkstreu" (Loyalty to the State and Loyalty to the [German] People), the Kulturbund promoted the representation of the German culture and ethnic identity, but in active cooperation with the Yugoslav government and the Slavic ethnic majourity.

This initial moderation was gradually transformed under the firebrand polemics of pan-Germanic nationalists like Branimir Altgayer, Dr. Jakob Anwender, and Dr. Sepp Janko in response to the increasing hegemony of the Serbian dictatorship over the German community and other minourities. Various ideological currents competed in town hall and academic debates between liberals, radicals, and conservatives. The ascension of the National Socialists in Germany under Adolf Hitler and the proliferation of pan-Germanic rhetoric greatly influenced the political evolution of the Yugoslav Germans. The image of pan-Germanic unity and collective vision of the Nazis in Germany inspired many Swabians who were increasingly angered by their diminution of autonomy under King Aleksandr. Land and property redistributions, although quite often exaggerated and equally imposed on Slavs and Germans alike, continued to pressure this divergence away from integration with Belgrade. So too, the declaration by the Romanian Fascist government that National Socialism was the sole representative voice of the Transylvania Saxons contributed to the radicalisation of the Yugoslav Swabians. The Kulturbund was, like most German diaspora groups, sponsoured and even subsidised by the Volksbund für das Deutschtum im Ausland (People's Federation for Germandom Abroad) and the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle, two cultural and academic organisations in the Third Reich devoted to promoting pan-Germanic ideology. Eventually, the two nationalist doctors succeeded in exploiting these geopolitical circumstances and guiding the Kulturbund and other German associations towards German nationalism and racial pride by the mid-1930's under a movement called the National Socialist Renewal Movement (nationalsozialistische Erneuerungsbewegung). Despite extolling ethnic nationalism and cultural solidarity, the Kulturbund maintained at least topical affiliation and cooperation with the Yugoslav state; it did not call for total independence, revolution, or promote any genocide.

By 1939,

the Nazified Kulturbund had become the most

salient political representative of the German minourity in

Yugoslavia. By the time of the Axis invasion, there were over

300,000 Kulturbund members, or over 60% of the total Yugoslav

German population (Sretenovic 2002, 50). In 1939,

the Kulturbund was absorbed into the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle

network of Heinrich Himmler, the director of the SS and the

prime architect of the Holocaust. As a result, the Yugoslav

Germans were subsequently represented, organised, and subsidised

by the Third Reich and the SS. Dr. Sepp Janko of the Kulturbund

became the "Führer" of the Yugoslav Swabians prior

to the Axis invasion. The broad membership of the Swabians

in Nazi movements contributed to the exaggerated post-war

identification of Swabians as being universally involved in

the Nazi atrocities committed by the foreign Axis armies.

Despite the fact that the Kulturbund and most Germans adopted

pan-Germanic and even racist rhetoric, the universalised assumption

by the Yugoslavs that the entire German ethnicity was collectively

guilty of genocide and should therefore be imprisoned was

vastly exaggerated.

Dr. Jakob Anwender in an SS-style uniform at left meeting

Croatian Nazi leader Ante Pavelic. Anwender, along with Sepp

Janko and other polemics, helped transform the hitherto moderate

Kulturbund into a racialist and pan-Germanic organisation

(source: mymilitaria.it)

The Axis invasion and the atrocities of the war

In March of 1941, the geopolitical position of Yugoslavia became precarious. King Aleksandr I, the dictator of Yugoslavia and a partial political and economic partner of the Third Reich under the Tripartite Pact, was overthrown in a coup by King Petar II with British support. The Western Allies, along with significant segments of the Yugoslav government, sought to reverse Yugoslavia's relationship with Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy. Yielding to pressure, Petar and the government finally chose to maintain adherence to the Tripartite Pact with the Axis and to support Germany's expansionist claims under the Vienna Agreement (Glenny 1999, 476). However, Hitler petulently answered the problem of Belgrade's uncertain relationship with Germany by declaring war on Yugoslavia. Most historians argue that Germany was relegated and reluctant to invade Yugoslavia in order to assuage Italian military failures in neighbouring Greece, and was greatly pressured by intensifying claims on Yugoslav land by Axis Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania. The incredibly sudden invasion of Yugoslavia and the last-minute coup by King Petar against the pro-Axis King Aleksandr greatly challenges the post-war Yugoslav myth that the Danube Swabians had been planning a longstanding conspiracy of Nazi invasion. So too, few Swabians (or Yugoslavs for that matter) could predict that Germany would destroy a crucial economic and political trading partner in the Tripartite Pact.

The former Yugoslavia was occupied and carved up between the Axis belligerents from 1941 to late 1944. King Petar II was thrown into exile. Bulgaria seized Macedonia; Italy annexed Slovenia, Montenegro, and the coastline of Bosnia and Croatia (Dalmatia); and Germany occupied Serbia proper. The Banat and Vojvodina regions of northern Serbia, where most Yugoslav Germans lived, were absorbed into Axis Hungary. Under Germany's orchestration, towns and municipalities in the Banat with German majourities were elevated to the status of an autonomous administrative exclave within the Third Reich, despite Germans being only 20% of the Banat's population (Hrvatski Informativni Centar). A puppet protectorate regime was set up under German direction in Belgrade under the Serb nationalist Milan Nedić. Croatian ultranationalists of the Ustaše movement broke from Yugoslavia, merged with Bosnia, and organised an extreme-right state supported by Italy and Germany called the Independent State of Croatia under Ante Pavelić. The leading position of Germany in the domination of the Yugoslavs, as well as their close affiliation with the Yugoslav Swabians, contributed to their universal identification as a criminal ethnic group by the vengeance-seeking socialists after the war.

What

followed was a tragic fracas of ethnic cleansings and genocide

committed by each ethnic group of the dismantled Yugoslavia,

as each identity violently seized the opportunity to struggle

for the independence and cultural franchise that were increasingly

denied to them by the Serb-dominated Yugoslav monarchy. Serbs,

Albanians, Croats, Bosnians, Muslims, Orthodox, Catholics,

Swabians, Hungarians, Communists, monarchist Četnik militias,

and Nazis all participated in a maelstrom of some of the bloodiest

atrocities of World War II. Dormant ethnic hatred between

Croats and Serbs decimated the Balkans, whilst Communist brigades

and Serb nationalists engaged in mutual massacres all across

the despoiled Yugoslav territories. The Swabian Germans and

Croats, however, were blamed for all of them after the war

and subjected to great reprisal and universal imprisonment.

Croatian Nazi leader Ante Pavelic at right shaking hands with

Adolf Hitler. Many Swabians were actively involved with the

Croatian-German partnership and its concomitant brutality

against Serbs, Jews, and other victims (source: axishistory.com)

It was at this time that the first phase of 'evacuation' and removal of the Yugoslav Germans occurred, not by vengeful Communists, but by the Third Reich itself. The small German populations outside of allied Croatia and the autonomous German region of the Banat were considered by Germany to be at risk of losing their 'pure' ethnic identity through assimilation or being killed by Communist partisan raids. It was believed by the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle under Heinrich Himmler that disparate German minourities in Slovenia, rural Bosnia, and Serbia proper would also enjoy greater representation and fiscal opportunities if they were transferred 'back home' to Germany, the home that their ancestors had not seen for two centuries. As a result of this policy, the entire German population of Bosnia-Herzegovina (then part of Nazi Croatia) was forcibly escorted to Belgrade, where they were gathered on trains and trucks and shipped northward to Axis Hungary, the Third Reich, or German-occupied Poland. In all, some 18,000 German civilians were relocated out of Bosnia in this fashion (Lumans 1993, 176). Most of the German community in Italian-ruled Slovenia known as the Gotschee Germans, previously totaling 33,000, were also 'evacuated' (Sretenovic 2004, 53), (Prokle 2003, 155). Some Germans did remain in Slovenia (until the socialists removed them after 1944), but Bosnia was completely depopulated of Germans by Germany. At least 1,925 Swabian civilians were removed from the rest of Yugoslavia (especially Serbia), ostensibly as a means of 'protection' against Yugoslav partisan assaults against German villages. Interestingly, many of these 'evacuations' were performed by the German army and the SS without the approval of the evacuated Swabian Germans. In some cases, it was even reported that ethnic Germans attacked SS escorts when they approached them for compulsory removal (Lumans 1993, 176). Like the Baltic Germans and many Germans of Romania, most of Bosnia's and Slovenia's Germans had disappeared as a result of Germany's foreign policy and its pan-Germanic ideology. However, this involuntary displacement was only a fraction of that performed by the Yugoslav socialist regime after the war against the German ethnicity altogether.

It is crucial to emphasise the complicity of each group in committing various forms of ethnic genocide in order to debunk the popular post-war myth that only the Germans were involved in atrocities and war crimes. Rather than the Axis powers causing the genocides, their destruction of the Belgrade monarchy spawned an almost inevitable civil war and a vacuum of power and ethnic violence. Nazi rule only ignited an already-dormant powder keg of violent cleansing. Yugoslavia endured some of the most casualties of the entire war. Over 900,000 died as a result of the Yugoslav civil war altogether. Most of this resulted not from genocide performed by the Swabian minourity, but from general skrimishes and massacres between rival Serb nationalists, Croats, monarchists, Nazi soldiers, and Communist partisans (Burleigh 2001, 421). Most of the Jews and Serbs of Bulgarian-occupied Macedonia were killed or expelled by Bulgaria, and in one event alone Hungarian soldiers in occupied Vojvodina executed over 4,000 civilians (mostly Jews and Serbs) in Novi Sad in 1942 (Yahil 2000, 503). The war crimes of the Croats are particularly important in relation to the fate of the Swabians because both of the two were depicted after the war as complicit Nazi belligerents. The Croatian nationalists, who adopted their own rendition of racialism and 'Aryan' identity, independently persecuted or murdered a higher percentage of its population in mob killings and Croatian concentration camps like Jasenovac than any other Axis country (Glenny 1999, 501). It has been estimated that 1/3 of the 2,000,000 Serbs in Croatia's southeastern region of Krajina and in eastern Bosnia were executed, 1/3 were forcbily assimilated and converted to Croatian Catholicism, and 1/3 were expelled (Ibid., 498). 75% of Croatia's Jews, or 30-40,000, died during the war (Cox 2002, 94). The atrocities of the Croats were so drastic that even the SS was supposedly 'shocked', and pressured the Croatian nationalists to slow down so as not to further radicalise the bellicose Communist partisans (Singleton 1985, 178). The Croats and Swabians of Yugoslavia hoped to expel as many as 50,000 Serbs from the Banat and Vojvodina, but Berlin allegedly refused for the same reason (Wolff 2002, 151).

However, the SS legions active in Yugoslavia that conscripted local Yugoslav Swabians did participate in many of the worst crimes performed by the Third Reich in any occupied nation. Following the Axis invasion, the German government organised the formation of volunteer militia, army (Wehrmacht), and Waffen-SS units. All recruits among Danube Swabians in the former Yugoslavia were placed under SS-Division Prinz Eugen led by the Transylvania Saxon Artur Phleps, one of the most barbaric and brutal of all SS units. The German administration issued a decree that for every ethnic German civilian or soldier killed by Yugoslav partisans, as many as 100 Slavic civilians would be shot in reprisals (Glenny 1999, 485). As a result of this policy, Slavic towns like Sutjeska, Nikšić, Kaljevo, and Neretva were virtually burnt to the ground and nearly all their inhabitants were executed. Over 20,000 Serbs were shot between Septembre 1941 and February 1942 alone, officially in reprisals (Burleigh 2001, 433). Thousands of Jewish and especially non-Jewish Slovene partisans, nationalists, and Communists were gassed or shot by German, volunteer, and Italian officers in the little-known concentration camp of Risiera di San Sabba in Trieste after 1943 in cooperation between Benito Mussolini and the Third Reich. The Germans (including Swabians and German soldiers), Croats, and Četnik Serbs killed 94% of Serbia's Jews, or 15-16,000 persons (Cox 2002, 92). Zrenjanin's Jews were almost completely vanquished. According to the official Croatian statistics bureau (Državni Zavod za Statistiku), the total Jewish population in Croatia dropped from about 20,000 to only 413 between 1931 and 1953, although this was primarily carried out by the Croats.

The Transylvania Saxon Artur Phleps, commander of SS-Division

Prinz Eugen, which recruited Swabians in Yugoslavia and committed

many of the worst atrocities of the war against the civilians

and partisans.

The degree of Yugoslav German civilians' involvement in war-time brutality

It is undeniable that the Third Reich committed and either encouraged or apathetically allowed brutal racial genocide, but it is very difficult to accurately assess the degree to which the average ethnic German civilian in occupied Yugoslavia was involved in the atrocities performed by the German army or other Axis powers. Sources that depict an entirely innocent Yugoslav German population that was subjected to mass persecution or 'extermination' by the Communists are exaggerated, as are arguments that portray the Swabians as 'Kulturbundists' who were universally involved in National Socialism, SS killing squads, or genocidal war crimes. Nonetheless, after 1944, the triumphant socialists universally proscribed the Germans and Hungarians with collective guilt as a 'Fifth Column' of traitors who uniformly cooperated with the invading Fascists.

The vast majourity of Swabians in Yugoslavia actively supported the Kulturbund, which espoused a pan-Germanic, nationalist, racialist, and pro-Hitler ideology prior to the Axis invasion in 1941. There were at least 300,000 registered members of the Kulturbund when Axis troops arrived (Sretenovic 2002, 50). At this time, there were over 500,000 total ethnic Germans within Yugoslav borders, meaning that some 60% of Swabians officially endorsed Kulturbundist ideology (Stupar). This does not include the unregistered number of Germans who sympathised with Nazi doctrines or pan-Germanic tendencies but did not officially join the party. However, like the Sudeten Germans of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia's Germans attached themselves to ethnic German nationalist movements because they were believed to best address their cultural and political interests. After King Aleksandr's dictatorship largely blocked Yugoslavia's minourity groups from actively maintaining their local autonomy and political franchise, this further encouraged Swabians to join German nationalist groups. Pro-German parties, even those adopting Nazi slogans, were far more relevant and appealing to the German minourity than the national Slavic parties that supported the monarchy that already stymied their cultural agency and political autonomy. Thus, the fact that most Swabians in Yugoslavia were 'Nazis' and members of the Kulturbund did not automatically equate to the attributes of Nazi barbarism and genocide with which we are unfortunately familiar today.

After the war, the Yugoslav socialists justified the proscription of the Yugoslav Germans by accusing them and the Kulturbund of a longstanding conspiracy with the Third Reich to orchestrate the invasion of Yugoslavia and subjugate the Slavs under the authority of the Swabian minourity (Portmann, 62). This allegation is presumptuous and largely baseless. As yet, no evidence has been located in historiography to indicate any conspiratorial collusion between the Kulturbund or Swabian groups with Nazi Germany prior to the invasion. The Kulturbund continuously espoused a programme of cooperation and membership within Yugoslavia, rather than any call for irredentism or independence. So too, as noted above, Yugoslavia and Germany were in close political and economic partnership under the Tripartite Pact. Yugoslavia was highly dependent upon the German economy and German investors (Singleton 1985, 156). 65% of Yugoslavia's imported products and machinery came from Germany, often at reduced rates. Few Swabians could have predicted that Berlin would obliterate such a positive economic and political union, which was maintained under the Tripartite Pact even until the invasion began. So too, few Swabians (or even Yugoslavs or Germans) could have predicted the last-minute coup against King Aleksandr in March of 1941 by the anti-Pact Petar II, or the incredibly impromptu declaration of war on Belgrade by Hitler in response to the monarchy's sudden uncertainty in political behaviour. Even after Petar II took power, he ultimately chose to maintain the ties with Germany (Glenny 1999, 476). There was insufficient time for the Yugoslav Swabians to plot a longstanding conspiracy with Hitler to destroy Yugoslavia. There was no enduring conspiracy for invasion and genocide against the Yugoslavs between the Swabians and the Third Reich, as the socialists claimed after the war when they began the imprisonment of the entire German community. Yugoslavia was just as much home to the Swabians as the Germany that their ancestors left some two centuries prior.

There were also a number of reported cases of resistance among Swabian Catholic priests and church circles against atrocities committed by the Wehrmacht, the SS, and other Danube Swabians against the Yugoslavs. Reports by the SS reveal that some Swabians in Serbia and Bosnia who were planned for evacuation to Germany without their approval even attacked their SS escorts (Lumans 1993, 176). So too, several liberal academic and civil associations expressed great resistance to the Nazification of the Swabian Germans, and strongly excoriated the violence committed by the Axis troops in occupied Yugoslavia. The liberal newspaper periodical 'Die Donau' (the Danube) represented an ideological current present among Danube Swabians that greatly challenges the post-war myth of a universal adherence of Yugoslavia's Germans to racialist Nazis extremism and perfidy. When the German and Hungarian troops arrived in the Serbian Vojvodina, churches and newspapers with a liberal or reactionary leaning among Hungarian and Swabian communities were banned, and many of their editors and priests were arrested or obliged into exile. Despite the diverse political and ideological beliefs of the Swabians, which further fragmented as the war turned against Germany, the Yugoslav socialists proceeded to persecute and gaol the entire ethnic group regardless.

It

is certain that large numbers of Danube Swabian men openly

welcomed and supported the Third Reich and even Nazi atrocities

during the period of occupation. Most were very unlikely to

reject the tremendous subsidy and support they received from

Germany in contrast to the impediment to their cultural franchise

they experienced under the Yugoslav monarchy after 1929. SS-Division

Prinz Eugen, which operated in Yugoslavia and drew from local

Swabian conscripts and volunteers, was one of the most truculent

of all SS units in its rampant executions of Slavic civilian

populations and the incineration of civilian villages. 93,000

Swabians served in either the army, military police, or SS

units of Germany, Croatia, or Hungary during the war, totaling

nearly 20% of the Swabian population (Prokle 2003, 31).

18,538 Swabians in Croatia joined the infamous killing squads

of the Croatian Ustaše or the German SS, or nearly 18% of

the total German population there (Lumans 1993, 238).

These are unusually high percentages for civilian populations

volunteering or being conscripted into occupying army units.

These statistics also do not consider the unofficial methods

by which Swabian civilians contributed to the German war effort.

However, the number of Swabians who 'volunteered' or were

recruited is with a sincere desire to support the Nazi occupation

and genocides is also debatable. All Swabian men in occupied

Yugoslavia and especially the Banat were compulsorily required

to serve the Third Reich in some fashion, either

by joining SS-Prinz Eugen, the Wehrmacht, or by providing

another service (Sper, Darko), (Lumans 1993,

235). Regardless of their diverse political beliefs and

their varied levels of approval for Nazism, Yugoslavia's German

civilians were effectively forced to become what Yugoslavs

would later identify as traitors and a pro-Fascist irredentist

'Fifth Column'. Therefore, even when Swabians participated

in the SS killing squads, the German minourity's level of

personal approval of the Nazi occupation or their betrayal

of Yugoslavia remained questionable. Quite simply, it is uncertain

in historiography as to what percentage of the Swabian population

was involved in the Axis war crimes that would warrant their

experience of persecution by the Yugoslavs after the war.

The socialists under Tito would resolve this question by universally

criminalising the German ethnic identity altogether. The fact

that only men were allowed to join the SS meant that most

of the women and children who were forced into prison camps

or expelled by the socialists after the war were innocent

of any direct involvement in wartime atrocities, not to mention

the uncertain number of men with political ideologies opposed

to Nazism or those who grew increasingly rejecting of the

brutality of the German army in Yugoslavia by the end of the

war. So too, it has been argued that most of the Swabian civilians

who were actively involved in criminal activity fled Yugoslavia

with the German and Hungarian armies after 1944, meaning that

most of those who stayed home in Yugoslavia (and most of those

who were persecuted and gaoled) were innocent and did not expect reprisals by the Yugoslavs.

The disappearance of 98.5% of the Yugoslav Germans through expulsion, forced labour, and mass emigration

By Octobre of 1944, the crumbling Third Reich was in retreat from occupied Yugoslavia, and the socialist partisans led by Jozip Broz 'Tito' were victorious over the Swabian and Croatian Fascists and the Serb Četnik militias. Initially enjoying the close military and political sponsourship of the Soviet Red Army, the new Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia proceeded to arrest segments of the population that were accused of promoting un-socialist 'bourgeois' ideology, supporting reactionary or pro-monarchist movements, or collaborating with the Axis belligerents. The entire Hungarian and German minourities of the reunified Yugoslavia, as well as a large number of Croats, were universally proscribed with suspicion and accused of universally supporting the invading German and Hungarian armies as subversive elements. The near entirety of the Swabian population of Yugoslavia was ordered to be either expelled to occupied Germany or Austria, or interned in prison or forced labour camps. The leading proponents of the Fascist movements among the minourities were, understandably, to be executed outright. Only those cited for conspicious resistance to Fascism or in close affiliation with the socialist partisans would be excluded from the internment camps. The elderly, the young, the infirm, and the women of the Swabian minourity were also subjected to the Yugoslav imprisonment programme, portrayed as enemies of the people and collaborators.

Jozip Broz 'Tito', revolutionary socialist leader and the

first and greatest president of Yugoslavia

It is difficult to determine the total number of German civilians who were subjected to the Yugoslav imprisonment or relegated to emigrate because of Yugoslav discrimination after the war. Very few ethnic Germans were directly expelled because Allied-occupied Germany and Austria denied them asylum, overburdened by more than 10,000,000 other resettled German expellees. Instead, the vast majourity chose to flee in reaction to the universalised discrimination that the Swabians received in early socialist Yugoslavia due to their accused association with genocide and Fascism. It can properly be assumed that a large proportion of those who fled before the end of the war were guilty of atrocities or direct contribution to the Nazi war effort. This also implies that a vast percentage of those who stayed home in Yugoslavia believed they would not be punished because they were not guilty of Nazi war crimes. Yugoslavia was as much their home as the Germany their ancestors had not seen in two centuries. There were at least 500,000 ethnic Germans in all of Yugoslavia prior to the Axis invasion of 1941 (Stupar), with some statistics citing as many as 541,000 (Prokle 2003, 155), others 520,000 (Los Angeles Times), and others 513,412 (Wolff 2002, 147), at about 4.21% of the total population of Yugoslavia. There were over 98,990 Swabians in Yugoslav Croatia, or 2.9% (Državni Zavod za Statistiku). The Banat and Vojvodina region, formed as an autonomous region of northern Serbia, had over 328,000 Germans (Wolff 2002, 147). Large numbers of Germans fled Yugoslavia at the end of the war, either out of a desire to immigrate to Germany or to escape the inevitable Yugoslav retaliation for Germany's war crimes. This further complicates calculating the exact number of ethnic Germans who were affected by the Yugoslav collective imprisonment policy after the war. The SS and SS-Division Prinz Eugen unsuccessfully organised evacuation contingencies after the war with the desire to relocate the Swabians to the Third Reich. As many as 70,000 Swabians are estimated to have fled the Banat when the Red Army arrived in late 1944 (Zentrum gegen Vertreibung). As many as 16.8% of the Germans in Yugoslavia may have died during the war (Sretenovic 2004, 57). One estimate projects that 10% of the highly-Nazified Banat fled before the end of the war, and 20,000 fled with the Croatian Nazis to Austria (Sretenovic 2004, 54). Official statistics estimate that there were at least 200,000 Germans in Yugoslavia after the war, a reduction of over half the population due to fleeing, retaliatory killings by Yugoslavs, and expulsions (Wehler 1980, 79), (Wengert). The total number of Germans affected by the Yugoslav imprisonment and forced labour programmes therefore encompassed a minimum of 200,000 persons. The vast decrease in the ethnic German population through emigration and fleeing makes it difficult to calculate how many died in Yugoslav camps. So too, it has been argued that as many as 70,000 ethnic Germans and Hungarians concealed their ethnic identity on statistics by masqueraded as Serbs or Croats in order to escape a feared status of discrimination (Ibid., 155). Nearly all of these superficially assimilated Germans would emigrate with the rest of the Swabian community. As a result, statistics may often prove deficient in fully reflecting the morose experience of the former German community of Yugoslavia.

Ultimately, the total German population of Yugoslavia would drop from over 500,000 in 1941 to only about 7,302 combined in the independent Yugoslav republics today, equating to a total loss of 98.5% of the Yugoslav Swabian community through fleeing, expulsion, and especially relegated emigration as an effort to alleviate their status of discrimination, imprisonment, ethnicity-based persecution, and suspicion.

The immediate response of the Yugoslav socialist army in Octobre of 1944 was to execute the leaders of Swabian Nazi and nationalist associations, especially the Kulturbund. Dr. Sepp Janko, the leader of the Kulturbund and the 'Führer' of the Danube Swabians as recognised by Heinrich Himmler, attained an asylum visa out of Yugoslavia from the Red Cross and, under the pseudonym Jose Petri, fled to Nazi-sympathetic Argentina. After being shot by firing squad or hanged in a show trial orchestrated by the Anti-Fascist Council of People's Liberation or the Department for the Protection of the People (Tito's equivalent of the Soviet NKVD), at least 7,000 persons were officially executed immediately, with a disproportionate share among non-Slavic minourities (Portmann, 59). Many dubious and nationalist-leaning sources refer to the period between August and October as 'Bloody Autumn', with thousands being butchered and piled in mass graves they dug for themselves before being shot. These claims are largely inaccurate and overstated. Nonetheless, official executions were followed by rampant personal and mob reprisals against a minourity ethnic group that was perceived as having oppressed the Yugoslavs so brutally during the war. As many as 100,000 Croats, Serb monarchists, Hungarians, and Swabians were killed by rogue pogroms and show trials immediately after the war (Burleigh 2001, 802). Many Yugoslavs exploited the opportunity to take personal private interest in the confiscation or execution of 'enemies of the people' because they could eliminate personal or commercial competitors. Accusations like 'Fascist' and 'enemy of the people' were universal terms that were readily tossed around and even applied to fervent anti-Fascist and liberal Swabians and Croats, a charge that in the early phases was addressed with almost certain execution or imprisonment (Ibid.). As many as 50,000 Croatian Nazi soldiers and 30,000 civilians from Croatia (including Swabian volunteers) were force marched at gunpoint by the Yugoslavs to the forest or the border of occupied Austria, either for execution or expulsion (Glenny 1999, 530). It is unknown in historiography exactly how many Serbs, Germans, and Croats were killed in the maelstrom of civil conflict that befell Yugoslavia after the war.

When

the Red Army arrived, the Soviet Union inflicted its own devastation

upon the Yugoslav German minourity, ostensibly as an act of

punishment for Germany's atrocities against the USSR during

the war. Many sources and personal accounts depict rampant

murders, theft, and acts of rape and sexual abuse committed

against the German and Hungarian women whilst Soviet commanders

looked the other way, although they tend to be unverified

and prone to exaggeration. Non-Slavic ethnic groups were particularly

targeted as elements of revolt or treason (Burleigh 2001,

786). The Red Army also compounded

the Yugoslav imprisonment policy by demanding that Yugoslavia

participate in the Soviet directive to deport thousands of

'pro-Axis' minourities to the USSR for forced labour. As was

inveighed upon the Transylvania

Saxons of Romania, the Soviets ordered the ethnic German

minourities in Eastern Europe either be expelled or deported

to labour camps and quarry mines in the Soviet Union as part

of the reconstruction effort. Many Germans were deported on

the same trains that the Croats and Germans had used to deport

Yugoslavia's Jews and other victims to Auschwitz and Croatian

death camps (Wolff 2002, 153). At least 27,000 ethnic

Germans in socialist Yugoslavia were forcibly escorted by

the Red Army or the Yugoslavs and shipped to the Ukrainian

SSR for compulsory labour (Wasserstein). At least

16% thereof died as a result of exhaustion, freezing, malnutrition,

and disease (Sretenovic 2004, 54-55). Other sources

cite far higher proportions ranging as high as 10,000 deaths,

or about 37% (Lukan 2006, 278n).

Yugoslav partisans escorting German (and Swabian) prisoners

-- many of them civilians who were forced to join the German

war effort -- either to POW camps or to trial (source: ww2incolor.com)

A smaller number of Swabians, especially those in border regions accused of irredentist activity, were force marched or expelled by train to the border of occupied Austria. The great majourity of these expelled Germans were denied entry by the Allies, as they were already overwhelmed by the resettlement of over 10,000,000 ethnic Germans expelled from Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe. As a result, most of the freight trains used to expel the Germans turned back and transferred their passengers to the imprisonment and labour camps with the remainder of the German minourity. Many Germans were able to escape when near the border, and were seldom deterred by the Yugoslav guards who intended to were previously ordered to expel them anyway. Hunger, hypothermia, and disease tolled many deaths on the long journey (Wengert). Those Germans who remained in Slovenia after the Nazi resettlement campaign (see above) were either expelled to nearby Austria or relocated to camps in Serbia and the Vojvodina (Wolff 2002, 154).

A massive

government programme of land, livestock, and property confiscation

was initiated in the interests of forging a socialist society

with a protected proletariat and a dismantled landowning class.

Under the redistribution programme, a maximum of 10 hectares

of arable land were allotted to each family (Crkvenčić,

36). Although this policy applied to all Yugoslavs regardless

of ethnicity, the more affluent German minourity in the north

was inordinately affected because of their integral role in

the economy as a majour class of business owners and commercial

entrepreneurs in the Vojvodina, Yugoslavia's bread basket.

Before the war, 80% of industrial material exported from the

Vojvodina was controlled by German families (Wolff 2002,

150). Predictably, as a minourity group with disproportionate

control of the economy and the labour force, the Germans were

bound to be a target of the socialist redistribution campaign.

As nearly all of the German population was removed from their

homes and transported to internment camps, their property,

businesses, and depopulated land were nationalised and often

resold or transferred to relocated Yugoslav farmers, especially

Serbs, Croats, Montenegrins, and Greeks (Crkvenčić, 36)

. Property was seized without compensation to the German minourity,

as it was derided with suspicion as a dangerous population

for Axis war atrocities. An

official government order read, '...a lot of Germans and Hungarians...were

hostile towards the Slavic population and committed crimes

organized by the occupation forces. Especially the domestic

Swabians acted barbarically towards the Serbs and others of

our nations. Thus it is necessary to thoroughly retaliate

upon all Germans and upon those Hungarians who have committed

war crimes...Further it is necessary to take care of abandoned

and enemy property' (Portmann, 62). More than

1,647,305 hectares were confiscated in total, and more than

38% (~637,939 ha) were seized from ethnic German families,

despite being less than 4% of the population (Portmann,

56). After being released from Yugoslav custody by 1948,

most Swabians returning to their homes found them to be occupied

by new owners, with their previous livelihood, businesses,

and livestock lost to the property confiscations.

The remainder of Yugoslavia's Germans who did not flee at the end of the war or were not deported were forcibly transported to rural prison or labour camps on trains and convoys. Many families recalled that they were allotted only 15 minutes by armed Yugoslav guards to gather whatevere property and clothes they could carry. What was left behind was forfeit. Many, including those saturated by rain and mud from being forced to work in fields, would not change their clothes for over a year (Wengert). The citizenship of ethnic Germans, with exceptions only in conspicious cases of anti-Fascist resistance, was revoked, and their civil rights in the new Yugoslavia were vastly diminshed (Belgrade 92 News). The German language was banned from all instruction and excoriated in public use in favour of Serbocroatian, although this was gradually assuaged by 1947. In general, all men who were physically able to work were separated from their wives, elders, and children, and sent to separate camps for compulsory labour, especially around farms and agricultural plots. Children, the sick, women, the infirm, and the elderly were shipped to separate internment camps and were not forced to work, but were unable to leave and were provided limited rations and medicine. Upon reaching maturity, male children previously confined to internment with their mothers and elders were transferred to the labour camps, separated from those not physically able. In total, there were over 40 camps that held some 200,000 German civilians (nearly the entire ethnic group) until 1948 (Portmann, 64). Several fortifications that were formerly used as death camps for Jews and other victims by the Germans and Croats during the war were redesigned for Swabian prisoners and labour (Glenny 1991, 531). Most internment camps were located in Serbia. Some of the most salient camps in Yugoslavia for German prisoners were located in Sremska Mitrovica, Svilara, Gakovo, Valpovo (Croatia), Molin, Jarak, Kruševlje, and Hesna. Many formerly German towns dating back to the subsidy of the Habsburg era, such as Knićanin (Rudolfsgnad) and Apatin, were completely repopulated by Yugoslavs, with the German population removed to nearby prison camps, transforming the architectural and demographic character of much of Yugoslavia and the Vojvodina from that of the Germans to the Slavic majourity.

Danube Swabians being escorted from their confiscated property

to labour or imprisonment camps (source: stefan-jaeger.net)

The conditions and experience of the German prisoners in Yugoslav camps were miserable and pernicious, although many sources and accounts are arguably prone to exaggeration. Swabian prisoners were not systematically starved or tortured, nor are claims of rampant ethnic brutality and rape by Yugoslav guards against German prisoners reliable. Some Serbs retort that the suffering of Swabians paled in comparison to that of Serbs during Axis occupation. However, the Yugoslav army and government were apathetic as to the phyical and material well-being of the German minourity, since it was depicted as a dangerous subversive ethnic group that cooperated with the Fascists and an enemy of the popular socialist revolution. In such restrictive quarters, disease was rampant, and was exacerbated by the malnourishment suffered by prisoners due to the low food rations provided by the government. In the imprisonment camps that held the elderly and young children, this famine extenuated the rate of mortality. For adult males in the labour camps, low rations and physical exhaustion further increased the death toll and the propensity for disease and infection. Overcrowded, unsanitary, and unheated wooden bunk quarters were filled with lice. Only 150 grams of bread and a small quantity of a watery soup derived from peas were provided to labourers, with survivor accounts deriding the irregular distribution of food (Wengert). The poor conditions endured by ethnic German prisoners was eschewed by the International Red Cross and the United States, the latter sending observers to the Yugoslav camps to supply the prisoners with better rations, medicine, and supplies that the Yugoslavs were criticised for intentionally not providing (Sper, Darko). American shipments of pesticides, especially DDT, gradually helped partly inhibit the spread of disease and infection in the sleeping quarters and labour farms (Stretenovic 2004, 56).

Many prisoners attempted to flee. Interestingly, guards were often reported as being passive to the departure of children from the internment camps, but inevitably maintained far greater control over the economically and agriculturally important prisoners in the male labour camps. Prisoners caught escaping were rarely punished or executed, exemplifying the fact that the Yugoslav treatment of the German minourity was more intended to contain and discriminate against what was perceived as a dangerous population rather than function as a programme of extermination as many dubious sources claim (Sper, Darko). Many survivors recall that when they successfully escaped, they struggled with further intensified starvation and exhaustion whilst they hid from Yugoslav soldiers or citizens who may have reported them to the authorities. Many fleeing children and adults drowned in nearby rivers and lakes. Hungry children escaped through barbed wire and begged for foods on the streets. Children devised an adaptive system of security, in which they placed white pebbles on the door steps of homes of citizens who were known to be beneficent to escaped German prisoners, and black pebbles in front of homes whose inhabitants were accused of beating them or escorting them to the guards of the prison camps (Los Angeles Times).

One phenomenon deeply ingrained in the historical memory of survivors and polemical sources was that of 'mass graves' that held deceased or killed German prisoners. In the so-called 'Bloody Autumn' that occurred at the end of the war, active members of Nazi movements or the SS, as well as civilians killed by mob pogroms simply because of their German ethnicity, were killed in an imbroglio of civil conflict and often forced to dig their own trench graves before being shot and buried. However, the large mass graves and anonymous headstones that dotted the countryside outside of Yugoslav labour camps for German prisoners were not a result of murder or ethnic cleansing, but of the rampant deaths from the poor conditions, hypothermia, exhaustion, and disease suffered in the camps. Some erudite documents assert a 50% death rate in the hardest Yugoslav camps, especially those intended for collective labour (Sretenovic 2004, 56). Upon death, German prisoners were simply discarded to the local cemetary, forest, or nearby field in anonymous individual or mass graves without headstones and without ceremonies. Survivors who recently returned to the former Yugoslavia to find the graves of their relatives from the labour camps have been unable to locate them. The Teletschka fields outside of the expansive prisoner camp at Rudolfsgnad (Knićanin) contain mass graves that are believed to hold as many as 12,500 deceased prisoners who, either from disease or exhaustion, died in Yugoslav camps to which they were confined simply because of their ethnic identity. Other sources correct that estimate down to a mass grave capacity of 9,000 at Teletschka (Hutterer). When rivers flooded from the heavy Serbian rain season, it was reported that corpses were occasionally unearthed from the mass graves by the torrent and deposited into nearby streams, which carried the bodies of German and Hungarian prisoners into nearby villages. Heads and limbs, including those of children, were seen protruding from the soil of the anonymous burial grounds (Sper, Darko).

Unmarked anonymous graves outside the labour camp of Valpovo.

(source: Veronika Wengert and eurasisches

Magazin)

Another unmarked mass graveyard outside the Yugoslav forced

labour camp of Valpovo. (source: Veronika Wengert and eurasisches

Magazin)

Calculating the total number of Swabians who died or starved in Yugoslav camps is difficult. It is uncertain what proportion of the total died as a result of forced labour, disease, or infirmity, and thus which deaths and grievances can be directly attributed to the Yugoslav government. The conditions in the camps, including malnutrition and disease, surely exacerbated this rate of death that many would not have otherwise endured. As most of the prisoners in the labour camps were physically-able adults, presumptions of death from 'natural causes' are unrealistic. Official West German government estimates from 1958 absurdly claimed that 523,000 were expelled and 135,000 died, meaning that more Germans were expelled than even lived in Yugoslavia in 1945 (SBD 1958). Well-researched sources estimate that at least 46,000 German prisoners from the Serbian Vojvodina alone died between Autumn of 944 and Spring of 1948 (Portmann, 64). Others calculate 48,447 total deaths recorded. At least 1,994 suffered an uncertain fate, having been removed from Yugoslav camps and shipped to the Soviet Union for labour in the Ukrainian SSR (Sretenovic 2004, 57). Over a third of the at least 3,000 men imprisoned in Valpovo (Croatia) alone for forced labour died from exersion (Wengert). Other estimates range as high as 52,000 (Los Angeles Times). Others even cite as many as 85,399 deaths, although this includes the war-time mutual ethnic brutality between Yugoslavia's ethnic groups from 1941 until 1948 (Wolff 2002, 154).

By 1947, the prison camps were so overfilled to capacity that Belgrade was relegated to grant a small percentage of Swabian prisoners amnesty (Glenny 1999, 531). All prison camps devoted to interning ethnic minourity groups were disbanded by the end of 1948. The government's perception of the German and Hungarian populations as inherently perfidious and dangerous was gradually replaced by a process of inter-ethnic political federalisation in Yugoslavia. The illegality of the German language in public and in academia was revoked, and the citizenship of the German minourity was superficially renewed. German families, having been separated into labour camps for adult males and prison camps for women and children, were now able to be reunited after almost four years. Some camps, like the heavy labour camp in Valpovo (Croatia), was closed down as early as late 1946. Ordered to return home, many released inmates found that their homes, businesses, and farmlands had been repopulated by Yugoslav families after government nationalisation, and were largely financially unable to purchase new homes due to the confiscation of property they endured at the end of the war. The Yugoslav government often orchestrated contractual agreements with Yugoslav citizens to house former German prisoners for menial services with promises of tax incentives (Sper, Darko). Some former prisoners even joined the Yugoslav army or even occasionally intermarried with Slavic ethnic groups, hoping to regain a position of stability and protection in the new socialist country in which they lived. As a result of the poverty inflicted on the Swabians by the Yugoslav government, many were relegated to perform menial labour and transient oddjobs for Yugoslav families as servants and on farms for several more years even after the internment camps were disbanded in order to earn enough money for a visa to flee Yugoslavia for Germany. In order to obtain an exit pass, a released German prisoner had to pay roughly 3 months worth of salary in order to renounce his citizenship and leave for Germany (Sretenovic 2004, 56).